![]()

Part 1

Balance of relationships

![]()

1 Relationality versus power politics

As China’s power grows, it is worthwhile to examine if current IR theory can explain its relations with major powers, such as the US and the EU, and smaller neighboring states. In the spring of 2013, when the then newly-inaugurated leaders of two great power nations—Chinese President Xi Jinping and US President Barack Obama—met, Obama had raised a range of global governance issues related to human rights, climate change and cybersecurity, whereas Xi sought to promote his notion of a “new type of great power relations”. Obama’s strategy seemed to be predominantly grounded in idealism, as he pushed for universal criteria to guide each governance issue, and possibly by a degree of realism, motivated by a desire to impose more pressure on a rising US competitor. Regardless, Xi seemed uninterested in negotiating these universal principles of governance and appeared almost insensitive to the relevance of different values to the Sino-US relationship. Rather, he suggested that the two powers establish an amiable relationship independent of their differences, one that avoids the confrontation expected of a possible power transition within a bipolar system (Calmes & Myers 2013).

At almost the same time, a similar if not sharper contrast between universal principles and relational concerns could be found in the China–European Union (EU) relationship, exemplified by the chronic issue of the arms embargo (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China or PRC 2013). In the face of China’s unsatisfactory human rights conditions, the embargo served as a strategy to actualize the EU’s self-image of being a “normative power” (EU Official 2003). However, for China, a bilateral relationship can never be normal under the circumstance of an embargo. The EU’s pursuit for a rule-based international society may prompt suspicion that China has never been judged as an equal of the EU (Kavalski 2013).

In addition to failing to respond with any defensive counter principle to cope with US and EU pressure, China—viewed as either a global bipolar power or a hierarchical regional power—tends to deny its own legitimacy of pursuing unilateral control over smaller neighbors. For example, China has refused to intervene in North Korea, even when facing the provocation of nuclear proliferation. A popular realist explanation suggests that China needs North Korea to balance against South Korea and the US (Bajoria 2010). This account fails to explain why China is far from effective or sufficiently active in assuaging North Korea’s recalcitrance to rejoin the negotiation table in earnest. Rather, China shifted towards a strategy that sought to engage and work with the US. Alternative realist wisdom suggests that this can be explained by China’s desire for North Korea’s natural resources; however, this explanation is undercut by the fact that China actually supplies natural resources to North Korea (Lin 2009). Contrary to these speculations, US President Donald Trump affirmed that Xi had once briefed him about his difficult position, revealing that the difficulty laid primarily in the long and complicated relationship between Beijing and Pyongyang (Wall Street Journal 2017).

Moving southwards, China appears entangled in a maritime dispute with Vietnam, yet the dispute has not prevented a bilateral agreement of strategic partnership between the two governments and a joint drill of maritime rescue between the two navies from taking place (Ma 2012). Even more strikingly, China’s relations with Myanmar have survived the ideological incongruence, contradicting size, opposing alliance, border and ethnic disputes, global intervention, and internal upheavals on both sides, to the extent that Myanmar has not resorted to either balancing or bandwagoning (Roy 2005). Their bilateral relations call for an unconventional explanation.

Contrary to Washington’s perceptions, increase in China’s power has not pushed it to commit to an idea of establishing a sphere of influence, including the South China Sea where Washington has perceived a China threat. China’s rebuttal hinges on the claim that no incident has ever occurred in the area that hinders free passage, reflects the logic that ensuring free passage has nothing to do with power. Instead, China is inclined toward the dyadic arrangements between China and each of all others. China’s stylistic pursuit of bilateral relationships with smaller neighbors as well as the ASEAN is consistent with its stress on bilateral relationships with the US and EU, regardless of the power status of the other side, although the issue area and substance of the relationship sought in each case vary.

According to the conventional wisdom, the foreign policy of all nations, including China, is driven by energy security (Collins et al. 2008, Copeland 1996, Lampton 2008, Ziegler 2006), China’s insistence on non-interventionism to the effect that it has lost vital sources of energy, as in the case of Libya (Piao 2011) is hard to explain. In Africa, China gave its consent to UN intervention in Sudan and Liberia in 2003 and 2007, despite them being China’s major suppliers of oil and timber, respectively. Notably, China’s consent was given only after securing the approval of regional organizations (i.e. the African Union and the Economic Community of West African States). These regional organizations, which appear so marginally in mainstream IRT, have proven critical to the settlements reached between China, the UN, and local authorities.

A theory to explain a rising China’s consistent practices of gift-giving as well as its relative disinterest in global governance principles is thus needed. Explanations from within China draw on the notions of peaceful coexistence, a harmonious world, and a peaceful development; however, these fail to explain cases where China has not hesitated to resort to limited sanctions or coercion. Neither Vietnam, the Philippines, nor Taiwan is likely to characterize China’s maritime policy as harmonious. Nevertheless, China has demonstrated a seemingly counterintuitive refrain from taking territories where it has an upper hand, as in the case of North Korea and Myanmar, while exercising military determination where it has no capacity or even intention for immediate take over, as in the South China Sea, East China Sea, or Taiwan Straits.

This chapter explains theoretically the relational concerns in Chinese foreign policy and their implications for understanding IR. We argue that Chinese foreign policy is guided by the principles of BoR, and relationship is defined as the process of mutual constitution. States achieve mutual constitution by way of improvising imagined resemblances between them. BoR stresses the key concepts of practice, self-restraint, and bilaterality. It reflects a systemic commitment by states to avoid disorder under anarchy by seeking long-term reciprocal IR, regardless of prior differences in values, institutions, and power status.

BoR differs to BoP, where self-help typically characterizes foreign policy. Self-restraint is what informs foreign policy under BoR. A state relies on self-restraint to acquire all kinds of relationships and may revoke self-restraint to rectify a relationship that is perceived as unsustainable or wrong. In addition, offering of benevolence makes a proactive kind of self-restraint. This is called gift-giving in the Sinosphere, but we argue that BoR transcends Chinese conditions. Through this facilitation of self-restraint, the relational constitution of the state reduces disorder between separate states. BoR theory surpasses civilizational divides and the epistemological gap between rationality and culture by always searching for localized or even individualized routes to access BoR.

Most theories perceive IR as structures independent of the maneuvering of individual nations. Specifically, these theories always consider power as a property, never a relation (Baldwin 2004). Alternatively, BoR considers a state as the agent of relationships. We reiterate Giddens’s (1984) structuration theory and perceive BoR as a structurational mechanism recognizing the relevance of strategic choices of a state in reproducing or revising IR to constantly redefine the state, through the multiple and changing dimensions of relationality. Nevertheless, we do not treat the agent as a pregiven. Rather, we consider the agent as a constituted identity, rendering agential identities unstable at best and contingent upon the relationships incurred. The notion of “relationship” treats the phenomenon of the double standard in all countries’ foreign policies as a systemic necessity. This treatment provides a universal frame to explain inconsistency in foreign policy, which other IRTs easily throw into the theoretically irrelevant category of idiosyncrasy or hypocrisy (Hui 2005, Yan 2011).

Self-restraint: statist and Confucian

IR can be more conveniently dealt with where states perceive resemblance to one another in terms of their shared identity, rules of conduct, or necessities of power. Contemporary IRTs emphasize these imagined strings of resemblance between states. However, at times, states may defy a presumably shared identity, agreed upon rules, or power structure. Instead of reducing these incidents to idiosyncratic reasons, BoR theory aims to explain how these cases of defiance or double standard follow a plausible logic that is equally, if not more, convincing and attractive to states in the face of unwanted disorder in the imagined condition of anarchy. Imperfect politics of identity, rule making, and structuration compose a systemic incentive for states to resort to the strategy of BoR. By opening the state to relationality, IRT informed by BoR presents the rationale for a predominant number of those acting in the name of the state to deviate from the established patterns registered in other strings of IRT.

Our relational sensibilities are distinct from other positions arising out of the relational turn in social science. The relational turn generally disputes substantialism that regards actors or agents as ontologically pre-given (Crossley 2010, Donati 2010, Emirbayer 1997). However, no consensus has been reached on the extent to which actors are external to the process of engaging in reflexive or even subconscious selection to remain being a self (Burkitt 2016, Depelteau 2008, 2013, Selg 2016). The relational turn in IR has not attended to such a debate in which the literature consistently treats states as reflexive actors or agents (Breiger et al. 2014, Cranmer, Heinrich & Desmarais 2014, Perliger & Pedahzur 2011). Chinese scholars subscribing to Confucianism would handle such a debate hypothetically by assuming that all agents and actors are part of the little selves together making an unthinking greater self. Little self is relational in the sense that the imagined greater self, by its own nature, constitutes each little self, which is capable of reflexive decision making. The reflexive decision making of a little self indirectly aids in actualizing the greater self in one way or another.

The Anglophone agenda with respect to the relational turn practically analyzes how actors are likely to behave according to their relational constitution, as informed by an imagined prior resemblance. By contrast, the Chinese agenda is preoccupied with how actors consciously contribute to the construction and reproduction of an imagined greater self, embedded in shared ancestors, which is too thin to guide actions without constant improvisation of relations in accordance with occasions. On the Chinese agenda, the agency of the actor lies in reciprocating between little selves to reproduce imagined resemblance that defines the greater self. Reciprocating symbolizes the existence of only one collective self. This certainly needs reconfirmation from time to time. The caveat is that abortion of reconfirmation could incur political control. Without conscious reconfirmation, however, the little self could lose reflexivity and harm the greater self and all other little selves constituted by the greater self.

Nevertheless, an implicit consensus exists between the Anglophone and the Sinophone relations. That is, no state can afford to practice pure unilateralism, not even the US during the prime of its hegemony or China during the peak of the Cultural-Revolution autarky. Unilateralism has only been applicable in the short-run and on specific issues. Moreover, it often exists more in rhetoric than in practice, being ultimately reliant on altercasting, which cannot occur in isolation from other actors. This book regards self-restraint as a meaningful point of connection between the two epistemologies. The universal virtue and practice of self-restraint, epistemologically differently informed at various geocultural sites, testifies to a systemic force everywhere that allows only those capable of self-restraint to survive evolution. Translating the meaning of Confucian self-restraint philosophically and empirically is key to the Confucian contribution to IR theorization.

Self-restraint serves as a norm that has been emphasized in statism and communitarianism, and it is similarly treated as a virtue in Christianity and Confucianism. Nevertheless, disparities exist between them in philosophical, institutional, and practical terms, resulting in diverse foreign-policy motivations. The liberal understanding of self-restraint acknowledges individuals’ prior given rights to pursue their respective interests. It functions most powerfully among resembling strangers belonging to the same community of practice, where it serves to organize individuals into synchronized role players, in order to prevent them from encroaching on others’ rights. Reaffirming the notion of mutual and self-respect, liberal self-restraint confirms the self-worth of every actor, hence the reproduction of an imagined self-subjectivity that independently determines national identity and confidently expects acceptance.

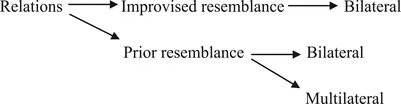

Relational identification confirmed by the voluntary observance of certain unowned, yet established, values and procedures among strangers ensures relations among these actors through the practice of shared norms. An implicit metaphor of domestic civic nationalism is noted, whereby citizens of different ethnic backgrounds develop joint loyalty to a state that enforces a particular set of social procedures irrespective to ethnicity. At international level, without a central authority to regulate interstate relations, self-restraint reflects the needs of states to mitigate anarchy and the potential disorder that comes with it. Constructivism falls back on this understanding of state agency to arrive at the realization that self-restraint is rational. However, for those cases where prior resemblance is lacking in general or inadequate in context, BoR adds the study of improvised relation to the relational turn. Without a prior consensus on rules or norms, enactment of resemblance has to almost entirely rely on gift giving of all sorts, such as zero interest loan, territorial concession, or support in an event. A properly devised benefit for the other state symbolizes and enacts resemblance of certain role identities, e.g. comradeship, brotherhood, and partnership, whose prior consensus is thin (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Two Kinds of Relationality

Source: Authors

Confucian self-restraint is such an acknowledgement of a “greater self” whose survival and wellbeing are the utmost priority. This greater self is practically thin and usually expressed through and reinforced by the metaphor of family. Confucian self-restraint incurs self-sacrifice, so it does not involve a reciprocal duty to exchange one’s own rights with those of equal others. Rather, it is an absolute duty to ensure the survival of the greater self and thus requires the suppression of self-worth. This sense of duty necessitates the reciprocal self-restraint toward others, who presumably resemble one another in terms of their relationship with the greater self. Self-restraint that contributes to other little selves is always idiosyncratic, as opposed to communities of strangers abiding to universal values and procedures. Relational security arising from belonging to the greater self transcends differences in ethnicity, regime type, power, and religion. The coexistence of differences is preserved by shunning the synchronization of specific thought foundations, such as liberalism.

Multilateral settings deprive Confucian actors of the legitimacy to pursue their own interests or enforce an allegedly universal value, lest these policies damage the greater self-identity among varieties. Consequently, Confucian self-restraint becomes a ritual in addition to a virtue. It is a required ritual in multilateral settings so as to reproduce relations among varieties. A bilateral setting makes only a slight difference from a multilateral one to a relationally minded liberal who exerts self-restraint, as the same procedures and values are observed to apply to both contexts, governing how an actor relates to strangers and associates alike. Under Confucianism, an actor achieves relational security through a shared practice of self-sacrifice, usually incurring specifically crafted gifts or favors. The exercise of self-restraint—understood as either concessions or sanctions in this book—vis-à-vis another specific state is tantamount to an invitation to form or reconfirm the existence of a specific greater self with the target state.

A cyclical view of history results from the use and withdrawal of self-restraint, with the former aimed at consolidating the greater self and the latter at rectifying a distorted greater self. Resembling little selves are equalized in their reciprocal contribution to the greater self. BoP can be deliberately disregarded at any moment to demonstrate the determination to ultimately protect the greater self. The stronger party can appear timid and the weaker party, aggressive. This is why the system of BoR can neutralize power disparity.

Theoretical propositions of BoR

The BoR addresses the dynamics of how two actors keep each other engaged in their imagined resemblance, constantly improvised by and for them to address general situations or in the face of a particular perceived incongruence. BoR,...