- 322 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

This book offers the first comparative monograph on the management of elections.

The book defines electoral management as a new, inter-disciplinary area and advances a realist sociological approach to study it. A series of new, original frameworks are introduced, including the PROSeS framework, which can be used by academics and practitioners around the world to evaluate electoral management quality. A networked governance approach is also introduced to understand the full range of collaborative actors involved in delivering elections, including civil society and the international community. Finally, the book evaluates some of the policy instruments used to improve the integrity of elections, including voter registration reform, training and the funding of elections. Extensive mixed methods are used throughout including thematic analysis of interviews, (auto-)ethnography, comparative historical analysis and, cross-national and national surveys of electoral officials.

This text will be of key interest to scholars, students and practitioners interested and involved in electoral integrity and elections, and more broadly to comparative politics, public administration, international relations and democracy studies.

Chapters 1 and 4 of this book are freely available as downloadable Open Access PDFs at http://www.taylorfrancis.com under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND) 4.0 license.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Foundations

1 Introduction

1.1 Why electoral management matters

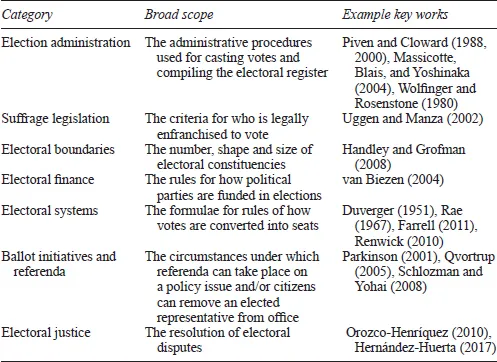

1.2 Electoral management: the new sub-field

1.3 Clarifying the terminology

1.4 Implementation involves rule-making and governance

- Organizing the actual electoral process (ranging from pre-election registration and campaigning, to the actual voting on election day, to post-election vote counting).

- Monitoring electoral conduct throughout the electoral process (i.e. monitoring the political party/candidates’ campaigns and media in the lead-up to elections, enforcing regulations regarding voter and party eligibility, campaign finance, campaign and media conduct, vote count and tallying procedures etc.).

- Certifying election results by declaring electoral outcomes.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Part I Foundations

- Part II Performance

- Part III Networks

- Part IV Instruments

- Part V Looking forward

- Bibliography

- Appendix: EMB budget sizes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app