![]()

Section V

Video and Digital Imagery for Self-Exploration

![]()

12

Video Modeling in the Art Classroom

Enhancing the Learning of Students With Autism Spectrum Disorder

Anthony Woodruff

Many of my former high school students were prone to displaying violent and aggressive behavior during instruction. I had students that would not communicate effectively with their peers or with me. There were students that would become upset if you made eye contact with them or talked with them directly. These students often had impaired social and communication skills, causing them to yell when they became frustrated. Even with these difficulties, these students could create remarkable works of art, had amazing personalities, and were among my favorite students to teach. It is easy to say I had an exciting, unique, intelligent, and creative group of students who just so happened to be diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Students with ASD are becoming more successful in their educational endeavors, including their art classes, as this disorder is being increasingly better understood.

Marked traits of this disability include significant impairments in both communication and social skills (Bellini, 2004) that can limit engagement in recreational and educational activities (APA, 2013). Because of these social deficits, students with ASD often have considerable difficulty interacting in social situations and establishing clear communication with others. Additionally, individuals with ASD frequently become fixated on potentially stigmatizing age-inappropriate activities and an unusual focus on highly restricted and fixated interests (APA, 2013). These restricted interests and social impairments further alienate and decrease engagement with typically developing peers when learning about art in the classroom setting. Due to their disabilities, students with ASD often struggle with acquiring and implementing new information from traditional teaching methods in their visual art classes. This struggle gives art educators the opportunity to try new teaching methods in order to see their students succeed.

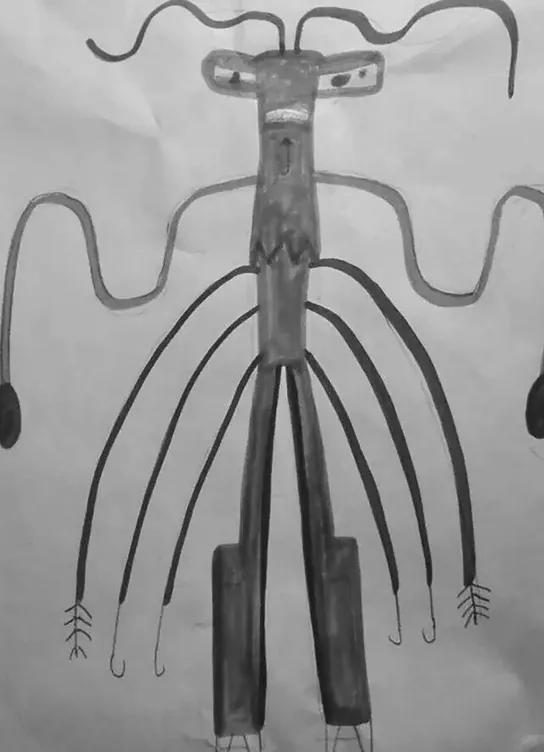

Even though learning about art was difficult in the art classroom, the majority of my former students with ASD created art independently in their free time without any direction (see Figures 12.1 and 12.2). A few students repeatedly drew famous singers, their friends, or various animals, while other students created more complex characters or illustrated short stories The same students who created all this art were also very skilled when it came to using technology. Another favorable free time activity was using a computer or tablet to watch videos and play video games. These students would often draw pictures or sing songs related to the videos they watched or games they played, demonstrating that information was being retained after these activities were over. While these students were having successful learning experiences in their recreational time, providing equally successful learning experiences became more difficult when entering the visual art classroom.

Due to social impairments and challenges with student/teacher interactions during traditional in vivo teaching methods like lecturing, demonstrations, or class discussions, students with ASD often have difficulties learning about the visual arts when teachers use these common pedagogical strategies. This chapter will share research results and give advice to visual art teachers seeking to remedy these issues by introducing a new teaching method applied in the art classroom, video modeling. Video modeling is widely used within the field of special education to teach a number of skills and can be easily applied to an art classroom setting. My former students with ASD acted as research participants, who were tested in both the development of art skills and their retention of art content knowledge through three common beginner art lessons: painting a color wheel, drawing a value scale, and sculpting a pinch pot.

Figure 12.1 and 12.2 Examples of art created by a student with ASD during independent recreational class time.

What Is Video Modeling?

Video modeling interventions have been shown effective in teaching a variety of skills to students with ASD and have become evidence based practice supported by numerous studies in special education research (Bellini & Akullian, 2007; Charlop-Christy, Le, & Freeman, 2000; Nikopoulos, Canavan, & Nikopoulou-Smyrni, 2009; Nikopoulos & Keenan, 2004; Sherrow, Spriggs, & Knight, 2015).

Video modeling is defined as a form of observational learning where a target behavior or skill is demonstrated on video, after which the learner has the opportunity to imitate the observed behavior or skill (Nikopoulos & Keenan, 2004). Researchers and special educators have used video modeling interventions with children with ASD to improve social skills, communication, recreational activities, and functional living skills. The acquisitions of these skills are vital for children with ASD as the disorder creates deficits in these areas. Nikopoulos and Keenan (2004) found that when exposed to video models, students with ASD showed higher levels of maintenance and retention of desired behaviors after watching video models of social initiations and play activities.

Bellini and Akullian (2007) completed a meta-analysis looking for the connection between video modeling and inventions for children and adolescents with ASD. They found results suggesting that video modeling is an effective intervention strategy for improving social communication skills, functional skills, and behavioral functioning in children and adolescents with ASD. Charlop-Christy et al. (2000) also showed that video based instruction led to faster acquisition and higher levels of generalization than traditional in vivo methods with students with ASD.

Likewise, the results of another study by Sherrow et al. (2015) showed a positive connection between video modeling and the learning of students with ASD. Their study demonstrated that video modeling could be an effective way to teach video games to students with both ASD and other cognitive disabilities. After low levels of success during baseline testing, participants were successful in reaching mastery of skills within a relatively short period of time while using video interventions. Overall, research has shown video modeling to be a successful tool for teaching students with ASD due to the challenges brought on by their disability.

Implementing video modeling into the classroom has become streamlined for all educators and simple steps have been adapted from a number of sources (LaCava, 2008; Sigafoos, O’Reilly, & de la Cruz, 2007). The video modeling process begins when teachers target a specific and measurable skill to be taught to their students. With the right equipment and planning completed, teachers can collect baseline data. When students start using the newly created video model, teachers should collect data on student performance being sure to note what steps in the skill are being completed independently after watching the video model. If a student is not advancing as expected, step nine involves troubleshooting to identify any needed changes to the video or environment. The final step, step ten, requires educators to slowly fade the video model and any accompanying prompting out, in order for the student to complete the task independently (LaCava, 2008; Sigafoos et al., 2007).

Teaching students through video modeling becomes even easier as today’s students are growing up in an ever-increasingly digital age. Students are being raised in a society that is changing rapidly and as a result of the influx of new technologies, we have been provided with faster links to communication, commerce, and culture. With those improvements, students have easier access and increased engagement with technology as well. Art educators should recognize the benefits of technology and the successes of special education when trying to enhance the learning of their students with ASD.

Figure 12.3 and 12.4 Student creating pinch pot independently during a follow up probe without the use of a video model or prompting.

Learning Socially and Inclusive Art Making

In order to capture the full uniqueness of the learning process for students with ASD, many theories have been accepted as best practices and are used to varying degrees in common teaching practices. The learning theories presented by Albert Bandura (1986) and Lev Vygotsky (1978) highlight the importance of the social domain, which have major teaching implications for students. More importantly to this chapter, the work of both these theorists can be found in the video modeling process, which has shown to be successful in working with students with ASD.

Bandura’s social cognitive theory involves a series of shared interactions between personal, behavioral, and the environment factors. In social cognitive theory, Bandura (1986) described learning as, “largely an information processing activity in which information about the structure of behavior and about environmental events is transformed into symbolic representations that serve as guides for actions” (p. 51). Social cognitive theory involves two modes of learning; either inactively through the actual doing of the task or vicariously by observing models performing the task first. Whether learning is achieved inactively or vicariously, another critical component to social cognitive theory is that learning, whether it be behavioral or cognitive, comes from the observation of other people who model the learning activity first. In Bandura’s theory students learn first by observing others, then improve their skills by practicing the task individually.

Social cognitive theory has proven itself to be a successful learning theory, but Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory is another effective theory as well. Vygotsky’s theory also incorporated the social aspect of learning, but with an even greater emphasis. Vygotsky (1978) contended that interactions between the social, historical and cultural, and individual factors are the key to creating meaningful activities that lead to human development. Among the three, Vygotsky considered the social environment to be the most critical for learning, and thought of social experiences as phenomena that explain changes in the consciousness.

Vygotsky’s (1978) defined the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), the key concept behind sociocultural theory, as “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers (p. 86).” The ZPD represents the amount of learning that is possible when students work with more capable peers when solving a problem.

Applying these two theories can be easily done when teaching students with ASD through the use of video modeling. The main tenets of Bandura and Vygotsky are naturally embedded into video modeling process. Video modeling includes Bandura’s theory as students learn vicariously by observing models performing the task first. Vygotsky’s ZPD is incorporated into video modeling as the model within the video acts as the more capable peer that the student can learn from. Video modeling may become even more successful when paired with Inclusive Arts.

The concept of Inclusive Arts allows for more accessible and engaging lessons that benefit individuals with disabilities. Fox and Macpherson (2015) described inclusive arts as a creative collaboration between the disabled and the nondisabled in order to support increase in knowledge, skills, and competence within the arts. Inclusive arts is important for art educators to be aware of because it can help reveal the creative and artistic potential of people with developmental disabilities, facilitate different modes of communication, and promote individual self-advocacy (Fox & Macpherson, 2015). The main motivation around inclusive arts is the collaborations and coming together in order to make or experience art. Inclusive arts acknowledges students with disabilities to a greater degree and asks art educators to fully incorporate all students into the lesson.

Art and Autism

According to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (2004), students with disabilities must have the same access to education as their nondisabled peers, and this includes the opportunity to express their creativity and develop skills in the visual arts. Due to their deficits, students may have a hard time engaging in art activities appropriately without the one-on-one attention or specialized methods that may be required. But even with those difficulties, students with ASD have benefited from exposure to art.

Misconceptions regarding low intellectual abilities in students with ASD present potential barriers for providing meaningful learning experiences and should be avoided by educators and student peers. Utilizing inappropriate materials, such as juvenile coloring books or having the student’s paraeducator complete the project for them is not only unnecessary, but it deprives the student of their right to equally access the curriculum (Burdick, 2011). The misconceptions that students with ASD lack the required skills to participate in art-making activities have been dispelled as students with autism continue to create art (Gerber & Kellman, 2010) and benefit from their experience...