eBook - ePub

Japanese Foreign Investments, 1970-98

Perspectives and Analyses

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Drawing on numerous Japanese and non-Japanese primary and secondary sources, this highly informative book analyzes all aspects (both domestic and international) of foreign direct investment made by Japan's multinational corporations in Asia, the European Union, and the U.S. It covers the critical period from 1970 -- the point at which Japan's economy reached a level of global importance -- through 1998 -- the nadir of Japan's economic woes. The book offers numerous perspectives to explain the changing characteristics of Japan's FDI practices over the period. The text is well supported by some 50 figures and data tables compiled from both Japanese government ministries and multinational corporations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Japanese Foreign Investments, 1970-98 by Dipak R. Basu,Victoria Miroshnik in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Recent Trends in International Capital Flows

Capital flows throughout the world in recent years have become more free and flexible than ever before. Immense amounts of capital are flowing between Japan and the United States. Some significant amounts, although much less than the Japan–U.S. flows, are between the developed countries and the developing countries. The economic significance of the later capital flows on the future of the world economy can be even more significant.

In the 1970s, international banks were the most important players in the international capital. Massive amounts of petrodollars were transferred between the oil-producing nations and the borrowing countries during that period. In 1996, net international banks lending was $315 billion, whereas it was only $190 billion in 1995, but now the role of the banks has become smaller than what it was twenty years ago. Although Asian countries are still major borrowers, the direct investments, mergers, and acquisitions are now more important than ever. Recently, port-folio investments in bonds and equities became very important, accounting for more than half of the private sector capital outflows from the developed countries. Official purchases of bonds can be very important at the time of exchange-rate interventions.

All these capital flows are normally very volatile. These are highly sensitive to the changes in the stock markets and changes in the balance of payments of different countries. Some of these flows reflect speculative activities in the foreign exchange markets and stock markets. For example, Japan was running balance of payments surplus; thus, these inflows were not required to finance current account imbalances there. During the first six months of 1996, about U.S.$44 billion flowed into the Japanese equity market with the view that the yen would be weaker than the dollar, and, thus, the Japanese corporate sector would be revived, which did not materialized. In fact, these capital inflows made compensating central bank purchases of U.S. treasury bonds essential in order to stabilize the yen against the dollar.

After World War II, the economic regeneration of Japan was spectacular. Since the 1980s, after gaining special positions and economic maturity through effective utilizations of the world trading system, Japan became a large exporter of investments. Initially, Japanese investments started in order to avoid the tariff walls set up by the European countries, but recently, due to the strengthening of the exchange rate of the yen and continuous improvements of the wage rates in Japan, it is no longer profitable for large Japanese multinational corporations to produce at home. In order to maintain their share in the international market, Japanese corporations are increasingly shifting their production bases to overseas countries with lower wage rates. Following the lead of some large corporations, Japanese medium-size companies as well are moving overseas.

For many years, international investments were nothing but large-scale purchases of U.S. bonds—both treasuries and corporates. These purchases have been linked to the persistent need to finance the U.S. balance of payments deficits of about $150 billion a year. In 1995, these foreign capital flows into the U.S. bond market went up to $220 billion. That was because the investments by Southeast Asian central banks supplemented normal private sector flows after the conversion of the yen to dollars. Central bank intervention is normally due to political motives; however, private sector portfolio investors have specific economic objectives, and in bonds, they seek strength in currency and high yields, whereas in equities, the objective is for diversification and growth.

Bond and equity flows tend to be different. In 1995, there was little foreign buying of U.S. equities in sharp contrast to what was going on in bonds, whereas the recent heavy buying of Japanese equities has not been matched by bond purchases. In 1995, foreigners were big buyers of German bonds, but they have been net sellers of French bonds. That was because French bond yields have been driven down to some unattractive levels due to tax breaks available to the domestic French investors when they buy government bonds through life insurance policies.

Emerging markets show some of the most volatile flows of all. International money of $62 billion boosted the emerging equity markets in 1993, but after setbacks in Hong Kong, Mexico, and elsewhere in East Asia, the flow was reduced to $20 billion by 1995. In 1996, once again, it has reached $40 to $50 billion. Thus, investors who enjoy risk have a lot of scope in China and India along with Eastern Europe. However, success in the emerging market has been damped by economic and political setbacks during 1997 in some of the most important Asian markets such as Korea, Thailand, and Indonesia due to their dire financial difficulties. Vast sums are available to be channeled into attractive opportunities; however, that money is highly sensitive to the least signs of trouble.

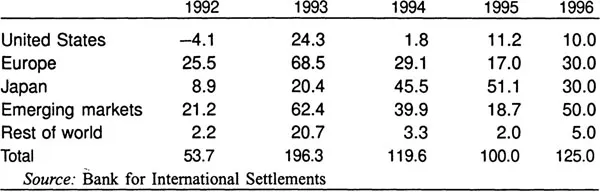

Table 1.1 shows the ups and downs of the attractiveness of various countries and regions for these equity flows. The United States, which was not a favorable destination in 1992, became very attractive in 1993 and very unattractive in 1994. Japan has maintained its attractiveness so far. Europe also has maintained its position as well.

Table 1.1

Net Cross-Border Equity Flows by Markets (US$ billion)

Corporate restructuring, particularly in sectors where deregulation or applications of new technologies are increasing competitive pressures, is one of the reasons for the growth in activity. Privatization, spurred by governments under pressure to raise cash in order to reduce fiscal deficits, has been responsible for some of the biggest deals. New demands for capital, coming from the emerging markets that lost access to international markets following the Mexican devaluation of December 1994, help to explain a surge in issuance of depositary receipt programs (paper that trades instead of underlying shares and helps investors avoid problems linked to settlement and custody in most markets).

Investors are responding positively to new international equity issues, partially reflecting the buoyancy of the secondary markets. U.S. institutional investors are continuing to switch their investments away from domestic markets. Also, European investors begin to follow suit. In response, international banks have increased the scale of the resources devoted to the international primary market, which became one of the most profitable investment banking activities. Most of the equities were issued in Europe, followed by the United States, Canada, and Asia. Other areas are lagging far behind.

Foreign Direct Investments

The total stock of foreign direct investments has exceeded $2,700 billion in 1996, double the amounts in 1988 and equal to about 10 percent of world economic output. Worldwide outflows have reached $318 billion in 1995, a 38 percent increase over 1994. The contributions of these inflows to host economies are becoming increasingly significant. In 1995, they represented 5.5 percent of total gross fixed capital formation, twice the level in the first half of the 1980s. As well as job creation, foreign direct investment brings transfer of technology and management expertise, exports, and the raising of skill levels. That is the reason why the most developing countries are trying to attract foreign investors and multinational companies. International institutions including the World Bank and United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) are urging developing countries to adopt the kind ofliberal, market-based economic strategies likely to create a congenial climate for investment inflows. One of the effects of these developments is the high proportion of international trade, more than a third of the total accounted for by intracompany transactions. The main factor behind this trend is the transnational spread of manufacturing and the development of global production networks.

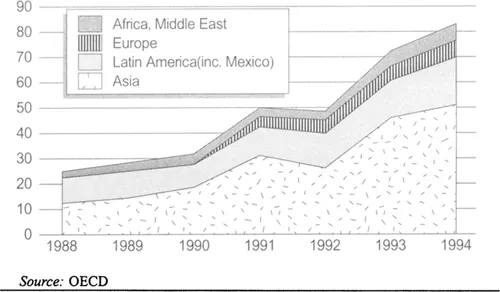

Figure 1.1 shows direct investment flows in the non-OECD areas. Asia is the biggest beneficiary, followed by Latin America. Other areas of Europe, Africa, and the Middle East were lagging far behind.

The rapid expansion of international trade in services underscores the traditional relationship between trade and investment. However, the geographical impact of foreign direct investments is still uneven. Despite the emergence of fast-growing economies in the developing world, industnalized countries absorbed two-thirds of worldwide inflows in 1995. This was a higher proportion than in 1982, just before the debt crisis of the Latin American countries. Industrialized countries were also the source of most of the outflows.

Figure 1.1 FDI Inflows in the Non-OECD Area ($ billion)

Imports from the developing world are increasing rapidly and now exceed exports of the developed countries to the developing world. This demonstrates increasing industrialization of the developing world and shifting of production bases to the developing world by multinational companies.

In spite of investments by Hong Kong and Taiwan in China and recent international expansion by South Korea’s conglomerates, most developing countries have yet to develop a multinational investment infrastructure. Most Western outflows in 1995 were for mergers and acquisitions. This was particularly true of the United States, which accounted for almost a third of the global outflows. Large acquisition opportunities are much more common in developed than in developing countries. The bulk of foreign direct investments in developing countries goes to about fifteen countries only. For instance, in 1995, China accounted for almost 40 percent of such inflows. Private capital flows into the developing world as a whole overtook official aid some years ago, but they have done little to help most poor countries.

The composition of foreign direct investment flows into developing countries is also strongly biased toward manufacturing. It often reflects undeveloped or heavily protected service sectors. Barriers occur particularly in banking and financial services, especially in Asian countries, which have been reluctant to deregulate financial markets. Malaysia, for example, for many years refused to license new foreign commercial banks. In telecommunications, the need to invest in modern networks created greater opportunities for outsiders. However, many developing countries still impose ownership limits on foreign investors. The persistence of such barriers has increasingly proved a stumbling block to the efforts of the World Trade Organization to liberalize trade in services. The United States has declined to participate in an agreement on financial services on the ground that not enough developing countries were ready to relax curbs on foreign ownership.

Characteristics of International Capital Inflows

The prospect for an increase in international capital flows toward the developing world is bright. Reforms in the way governments and multinational institutions treat very poor nations are helping to ensure that these countries receive more public money and stand a better chance of attracting private sector capital in future.

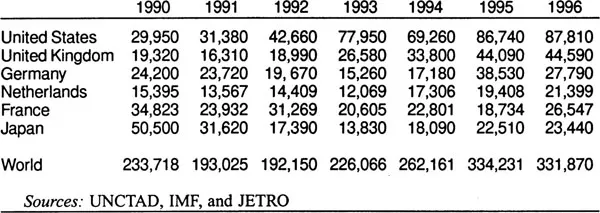

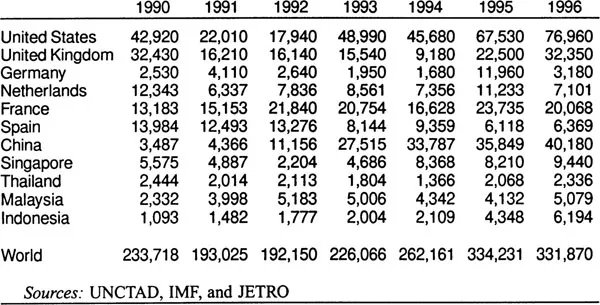

Table 1.2 shows direct investment outflows during the 1990s. During the 1990s, Japan along with France, the United States, Germany, and the UK are the most important countries regarding international capital flows, and Japan was the foremost country among them. In 1995, Japan was replaced by the United States as the most important contributor. Japan and Germany are not major recipients of direct investments, but the United States, UK, and France, are (Table 1.3). Direct investment outflows of Japan and Germany are due to their domestic factors, that is, high wages, high exchange rates, and balance of payments surplus. For the United States, UK, and France, direct investments are caused by increased competition posed by foreign firms, forcing domestic firms to move abroad to reduce their costs of production and to capture new markets. Several important developments occurred in official financing for developing countries recently. In December 1994, the agreement of the Paris Club of creditor nations allowed up to 67 percent debt reliefs for selected poor countries that have resolved their outstanding debt problems and prepared for reentry into the world financial community and possibly into the capital markets. There are proposals to alleviate a large part of the burden of multilateral debts. The World Bank’s proposed Trust Fund and the plan to sell a proportion of the International Monetary Funds (IMF’s) gold reserves would be used to finance this objective. Such initiatives would not only lessen the burden imposed on poor countries of large debt interest payments, but would also greatly increase the abilities ofthese countries to attract new capital from private financial markets.

Table 1.2

Outflow of Foreign Investments by Major Countries Based on the Balance of Payments (US$ million)

Table 1.3

Inflows of FDI in Major Countries Based on the Balance of Payments (US$ million)

Another important development in official financing was the support for Mexico in early 1995 and the support for the East Asian countries and Brazil in 1998. Subsequent efforts were made to create safeguards to ensure that financial turmoils like that of Mexico and of East Asia are less likely to happen again. These safeguards, such as better financial supervision and data standards, larger emergency credit arrangements and recommendations to ensure a fairer deal for creditors in case of a crisis, represent an attempt to set up a framework of checks and balances in which countries can operate without government interference and more effectively attract sustainable investment flows.

The flow of capital via securities into the developing world has managed to withstand the sharp rise in U.S. long-term interest rates at the beginning of 1996. Rise in the share of foreign direct investment inflows going into countries outside the OECD area increased since the late 1980s. The flow into the developing countries reached about $80 billion in 1994. Deregulations, privatization, and liberalization include dismantling of trade barriers in these countries. They have created an environment more conducive to inward investment.

However, the most important factor is the rapid economic growth in many developing countries. As economies of developing countries grew, the incentive for foreign companies to locate in these growing consumer markets increased significantly.

Japan has invested in a significant way in East Asia. The Asian newly industrializing economies (NIEs, i.e., Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore) are the most important destinations for Japanese direct investments. For the United States as well, these countries are very important, but Japan is the more important destination for U.S. foreign investments in East Asia. For the European Union (EU) as well, Japan is the more important destination than any other East Asian country. The attractiveness of China is falling for both the United States and Japan, but the EU still considers China attractive. China also receives a lion’s share of direct investments f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- 1. Recent Trends in International Capital Flows

- 2. Government Attitudes and Environments for Foreign Investments

- 3. Japan’S Overseas Investments: An Historical Analysis

- 4. Japan and Asian Economies

- 5. Impacts of Overseas Business Activities on Trade and Domestic Production in Japan

- 6. Asian Economic Crisis and the Role of Japan

- 7. Strategic Management of Japanese Multinationals

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Authors