- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This substantial account of Constantinople — or Istanbul as it is known today — is both a history and a guide to that magnificent and fabled metropolis where east and west have met for many centuries. Written in 1915 when, as Stamboul, the city was the last stop on the Orient Express, it is illustrated with many rare period photographs. This book for the general reader evokes all the colour and richness of the ultimate oriental city, ancient capital of the Byzantine and Ottoman empires, captured on the brink of modernization in the first years after the revolution. The author describes everyday life in the city, - the features of permanent interest such as mosques, gardens, fountains, the traces of Byzantium and the quays of the Golden Horn as well as the feasts, custom's, festivals and holidays that once enlivened Constantinople but are now only a memory. The work concludes with an account of the revolution and of the effects of World War I on the city. This is a portrait of the Istanbul that all travellers hope to find - and still can, in the pages of this book.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Constantinople by Dwight,H.G. Dwight in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CONSTANTINOPLE OLD AND NEW

I

Stamboul

IF literature could be governed by law — which, very happily, to the despair of grammarians, it can not — there should be an act prohibiting any one, on pain of death, ever to quote again or adapt to private use Charles Lamb and his two races of men. No one is better aware of the necessity of such a law than the present scribe, as he struggles with the temptation to declare anew that there are two races of men. Where, for instance, do they betray themselves more perfectly than in Stamboul? You like Stamboul or you dislike Stamboul, and there seems to be no half-way ground between the two opinions. I notice, however, that conversion from the latter rank to the former is not impossible. I cannot say that I ever really belonged, myself, to the enemies of Stamboul. Stamboul entered too early into my consciousness and I was too early separated from her to ask myself questions; and it later happened to me to fall under a potent spell. But there came a day when I returned to Stamboul from Italy. I felt a scarcely definable change in the atmosphere as soon as we crossed the Danube. Strange letters decorated the sides of cars, a fez or two — shall I be pedantic enough to say that the word is really Jess? — appeared at car windows, peasants on station platforms had something about them that recalled youthful associations. The change grew more and more marked as we neared the Turkish frontier. And I realised to what it had been trending when at last we entered a breach of the old Byzantine wall and whistled through a long seaside quarter of wooden houses more tumble-down and unpainted than I remembered wooden houses could be, and dusty little gardens, and glimpses of a wide blue water through ruinous masonry, and people as out-at-elbow and down-at-the-heel as their houses, who even at that shining hour of a summer morning found time to smoke hubble-bubbles in tipsy little coffee-houses above the Marmora or to squat motionless on their heels beside the track and watch the fire-carriage of the unbeliever roll in from the West.

I have never forgotten — nor do successive experiences seem to dull the sharpness of the impression — that abysmal drop from the general European level of spruceness and solidity. Yet Stamboul, if you belong to the same race of men as I, has a way of rehabilitating herself in your eyes, perhaps even of making you adopt her point of view. Not that I shall try to gloss over her case. Stamboul is not for the race of men that must have trimness, smoothness, regularity, and modern conveniences, and the latest amusements. She has ambitions in that direction. I may live to see her attain them. I have already lived to see half of the Stamboul I once knew burn to the ground and the other half experiment in Haussmannising. But there is still enough of the old Stamboul left to leaven the new. It is very bumpy to drive over. It is ill-painted and out of repair. It is somewhat intermittently served by the scavenger. Its geography is almost past finding out, for no true map of it, in this year of grace 1914, as yet exists, and no man knows his street or number. What he knows is the fountain or the coffee-house near which he lives, and the quarter in which both are situated, named perhaps Coral, or Thick Beard, or Eats No Meat, or Sees Not Day; and it remains for you to find that quarter and that fountain. Nevertheless, if you belong to the race of men that is amused by such things, that is curious about the ways and thoughts of other men and feels under no responsibility to change them, that can see happy arrangements of light and shade, of form and colour, without having them pointed out and in very common materials, that is not repelled by things which look old and out of order, that is even attracted by things which do look so and therefore have a mellowness of tone and a richness of association — if you belong to this race of men you will like Stamboul, and the chances are that you will like it very much.

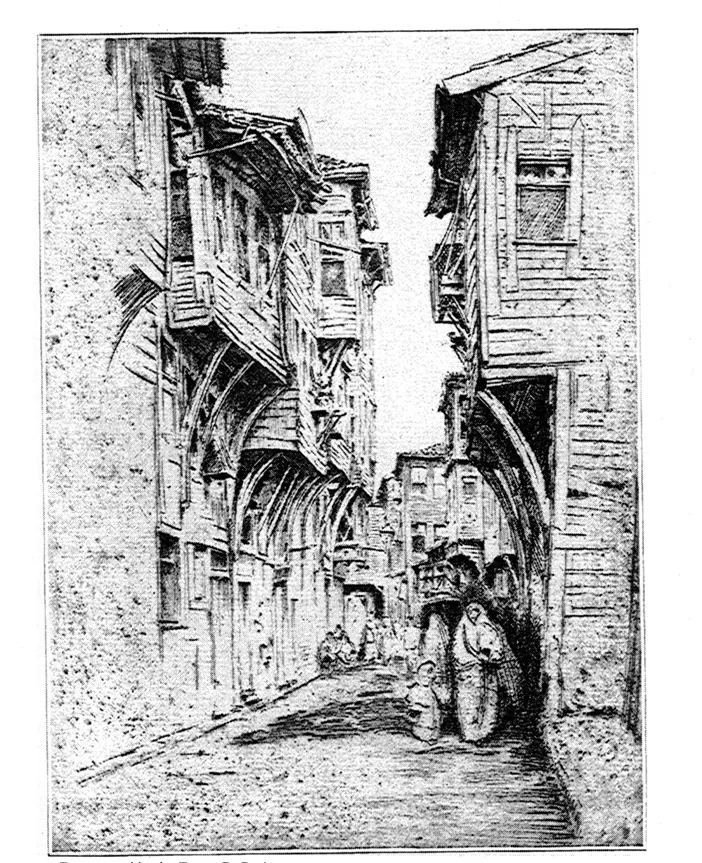

You must not make the other mistake, however, of expecting too much in the way of colour. Constantinople lies, it is true, in the same latitude as Naples; but the steppes of Russia are separated from it only by the not too boundless steppes of the Black Sea. The colour of Constantinople is a compromise, therefore, and not always a successful one, between north and south. While the sun shines for half the year, and summer rain is an exception, there is something hard and unsuffused about the light. Only on certain days of south wind are you reminded of the Mediterranean, and more rarely still of the autumn Adriatic. As for the town itself, it is no white southern city, being in tone one of the soberest. I could never bring myself, as some writers do, to speak of silvery domes. They are always covered with lead, which goes excellently with the stone of the mosques they crown. It is only the lesser minarets that are white; and here and there on some lifted pinnacle a small half-moon makes a flash of gold. While the high lights of Stamboul, then, are grey, this stone Stamboul is small in proportion to the darker Stamboul that fills the wide interstices between the mosques — a Stamboul of weathered wood that is just the colour of an etching. It has always seemed to me, indeed, that Stamboul, above all other cities I know, waits to be etched. Those fine lines of dome and minaret are for copper rather than canvas, while those crowded houses need the acid to bring out the richness of their shadows.

Stamboul has waited a long time. Besides Frank Brangwyn and E. D. Roth, I know of no etcher who has tried his needle there. And neither of those two has done what I could imagine Whistler doing — a Long Stamboul as seen from the opposite shore of the Golden Horn. When the archaeologists tell you that Constantinople, like Rome, is built on seven hills, don’t believe them. They are merely riding a hobby-horse so ancient that I, for one, am ashamed to mount it. Constantinople, or that part of it which is now Stamboul, lies on two hills, of which the more important is a long ridge dominating the Golden Horn. Its crest is not always at the same level, to be sure, and its slopes are naturally broken by ravines. If Rome, however, had been built on fourteen hills it would have been just as easy to find the same number in Constantinople. That steep promontory advancing between sea and sea toward a steeper Asia must always have been something to look at. But I find it hard to believe that the city of Constantine and Justinian can have marked so noble an outline against the sky as the city of the sultans. For the mosques of the sultans, placed exactly where their pyramids of domes and Iance-Iike minarets tell most against the light, are what make the silhouette of Stamboul one of the most notable things in the world.

From an etching by Ernest D. Roth

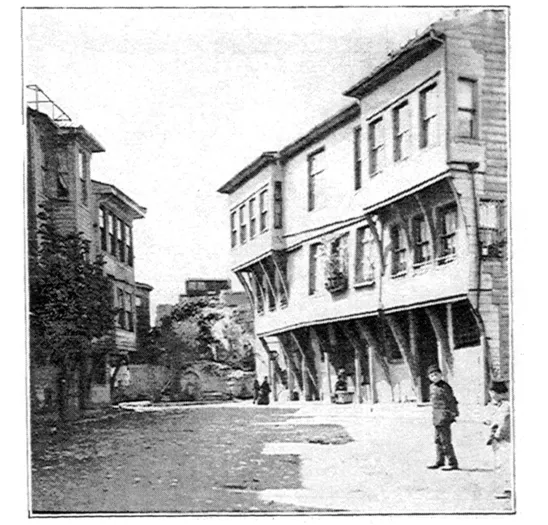

A Stamboul street

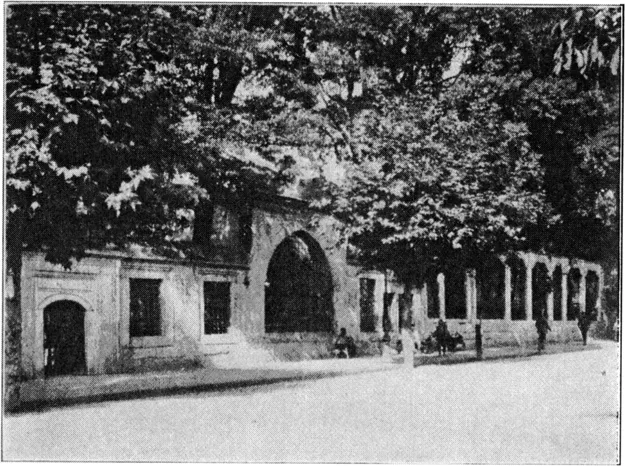

Of the many voyagers who have celebrated the panorama of Constantinople, not a few have recorded their disappointment on coming to closer acquaintance. De gustibus ... I have small respect, however, for the taste of those who find that the mosques will not bear inspection. I shall presently have something more particular to say in that matter. But since I am now speaking of the general aspects of Stamboul I can hardly pass over the part played by the mosques and their dependencies. A grey dome, a white minaret, a black cypress — that is the group which, recurring in every possible composition, makes up so much of the colour of the streets. On the monumental scale of the imperial mosques it ranks among the supreme architectural effects. On a smaller scale it never lacks charm. One element of this charm is so simple that I wonder it has not been more widely imitated. Almost every mosque is enclosed by a wall, sometimes of smooth ashler with a pointed coping, sometimes of plastered cobblestones tiled at the top, often tufted with snapdragon and camomile daisies. And this wall is pierced by a succession of windows which are filled with metal grille work as simple or as elaborate as the builder pleased. For he knew, the crafty man, that a grille or a lattice is always pleasant to look through, and that it somehow lends interest to the barest prospect.

There is hardly a street of Stamboul in which some such window does not give a glimpse into the peace and gravity of the East. The windows do not all look into mosque yards. Many of them open into the cloister of a medresseh, a theological school, or some other pious foundation. Many more look into a patch of ground where tall turbaned and Iichened stones lean among cypresses or where a more or less stately mausoleum, a türbeh, lifts its dome. Life and death seem never very far apart in Constantinople. In other cities the fact that life has an end is put out of sight as much as possible. Here it is not only acknowledged but taken advantage of for decorative purposes. Even Divan Yolou, the Street of the Council, which is the principal avenue of Stamboul, owes much of its character to the tombs and patches of cemetery that border it. Several sultans and grand viziers and any number of more obscure persons lie there neighbourly to the street, from which he who strolls, if not he who runs, may read — if Arabic letters be familiar to him — half the history of the empire.

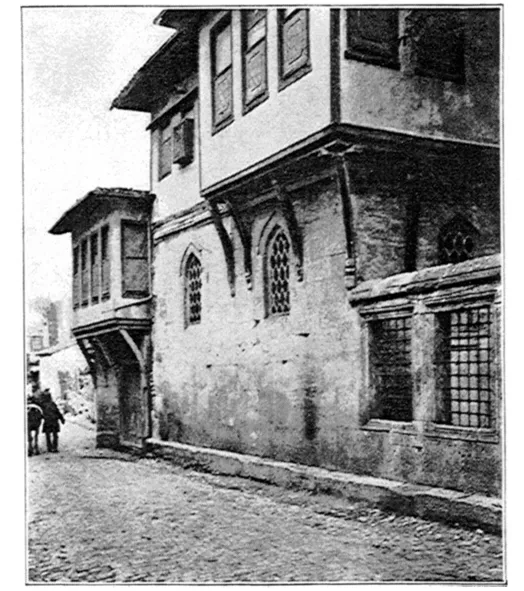

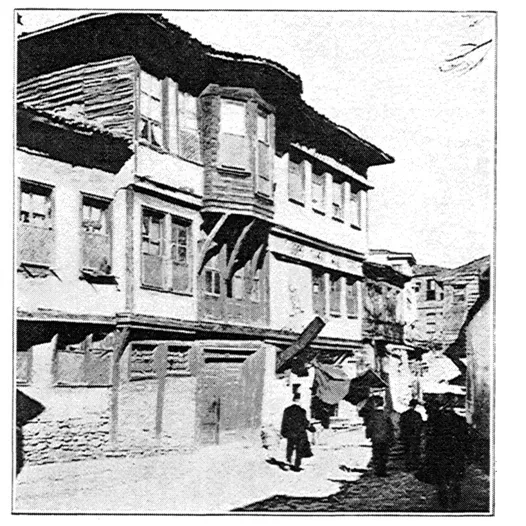

Of the houses of the living I have already hinted that they are less permanent in appearance. Until very recently they were all built of wood, and they all burned down ever so often. Consequently Stamboul has begun to rebuild herself in brick and concrete. I shall not complain of it, for I admit that it is not well for Stamboul to continue burning down. I also admit that Stamboul must modernise some of her habits. It is a matter of the greatest urgency if Stamboul wishes to continue to exist. Yet I am sorry to have the old wooden house of Stamboul disappear. It is not merely that I am a fanatic in things of other times. That house is, at its best, so expressive a piece of architecture, it is so simple and so dignified in its lines, it contains so much wisdom for the modern decorator, that I am sorry for it to disappear and leave no report of itself. If I could do what I like, there is nothing I should like to do more than to build, and to set a fashion of building, from less perishable materials, and fitted out with a little more convenience, a konak of Stamboul. They are descended, I suppose, from the old Byzantine houses. There is almost nothing Arabic about them, at all events, and their interior arrangement resembles that of any palazzo of the Renaissance.

Divan Yolou

The old wooden house of Stamboul is never very tall. It sits roomily on the ground, seldom rising above two storeys. Its effect resides in its symmetry and proportion, for there is almost no ornament about it. The doorway is the most decorative part of the façade. Its two leaves open very broad and square, with knockers in the form of lyres, or big rings attached to round plates of intricately perforated copper. Above it there will often be an oval light filled with a fan or star of swallow-tailed wooden radii. The windows in general make up a great part of the character of the house, so big and so numerous are they. They are all latticed, unless Christians happen to live in the house; but above the lattices is sometimes a second tier of windows, for light, whose small round or oval panes are decoratively set in broad white mullions of plaster. For the most original part of its effect, however, the house counts on its upper storey, which juts out over the street on stout timbers curved like the bow of a ship. Sometimes these corbels balance éach other right and left of the centre of the house, which may be rounded on the principle of a New York “swell front,” only more gracefully, and occasionally a third storey. leans out beyond the second. This arrangement gives more space to the upper floors than the ground itself affords and also assures a better view. If it incidentally narrows and darkens the street, I think the passer-by can only be grateful for the fine line of the curving brackets and for the summer shade. He is further protected from the sun by the broad eaves of the house, supported, perhaps, by little brackets of their own. Under them was stencilled of old an Arabic invocation, which more rarely decorated a blue-and-white tile and which nowadays is generally printed on paper and framed like a picture—“O Protector,” “O Conqueror,” “O Proprietor of all Property.” And over all is a low-pitched roof, hardly ever gabled, of the red tiles you see in Italy.

The inside of the house is almost as simple as the outside — or it used to be before Europe infected it. A great entrance hall, paved with marble, runs through the house from street to garden, for almost no house in Stamboul lacks its patch of green; and branching or double stairways lead to the upper regions. Other big halls are there, with niches and fountains set in the wall. The rooms opening out on either hand contain almost no furniture. The so-called Turkish corner which I fear is still the pride of some Western interiors never originated anywhere but in the diseased imagination of an upholsterer. The beauty of an old Turkish room does not depend on what may have been brought into it by chance, but on its own proportion and colour. On one side, covering the entire wall, should be a series of cupboards and niches, which may be charmingly decorated with painted flowers and gilt or coloured moulding. The ceiling is treated in the same way, the strips ol moulding being applied in some simple design. Of real woodcarving there is practically none, though the doors are panelled in great variety and the principle of the lattice is much used. There may also be a fireplace, not set off by a mantel, but by a tall pointed hood. And if there is a second tier of windows they may contain stained glass or some interesting scheme of mullioning. But do not look for chairs, tables, draperies, pictures, or any of the thousand gimcracks of the West that only fill a room without beautifying it. A long low divan runs under the windows, the whole length of the wall, or perhaps of two, furnished with rugs and embroidered cushions.

A house in Eyoub

A house at Aya Kapou

Other rugs, as fine as you please, cover the floor. Of wall space there is mercifully very little, for the windows crowd so closely together that there is no room to put anything between them, and the view is consciously made the chief ornament of the room. Still, on the inner walls may hang a text or two, written by or copied from some great calligraphist. The art of forming beautiful letters has been carried to great perfection by the Turks, who do not admit — or who until recently did not admit — any representation of living forms. Inscriptions, therefore, take with them the place of pictures, and they collect the work of famous calligraphs as Westerners collect other works of art. While a real appreciation of this art requires a knowledge which few foreigners possess, any foreigner should be able to take in the decorative value of the Arabic letters. There are various systems of forming them, and there is no limit to the number of ways in which they may be grouped. By adding to an inscription its reverse, it is possible to make a symmetrical figure which sometimes resembles a mosque, or the letters may be fancifully made to suggest a bird or a ship. Texts from the Koran, invocations of the Almighty, the names of the caliphs and of the companions of the Prophet, and verses of Persian poetry are all favourite subjects for the calligrapher. I have also seen what might very literally be called a word-picture of the Prophet. To paint a portrait of him would contravene all the traditions of the cult; but there exists a famous description of him which is sometimes written in a circle, as it were the outline of a head, on an illuminated panel.

The house of the pipe

However, I did not start out to describe the interior of Stamboul, of which I know as little as any man. That, indeed, is one element of the charm...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Of His Book

- Table of Contents

- Illustrations

- Chapter I Stamboul

- Chapter II Mosque Yards

- Chapter III Old Constantinople

- Chapter IV The Golden Horn

- Chapter V The Magnificent Community

- Chapter VI The City of Gold

- Chapter VII The Gardens of the Bosphorus

- Chapter VIII The Moon of Ramazan

- Chapter IX Mohammedan Holidays

- Chapter X Two Processions

- Chapter XI Greek Feasts

- Chapter XII Fountains

- Chapter XIII A Turkish Village

- Chapter XIV Revolution, 1908

- Chapter XV The Capture of Constantinople, 1909

- Chapter XVI War Time, 1912—1913

- Masters of Constantinople

- A Constantinople Book-Shelf

- Index