1 Introduction

What is the driving force of capitalism – consumption or profit? If it is consumption, then a shotgun or a rifle is just like any other private good, used for personal security or ‘pleasure’ (e.g. hunting), while a fighter jet or a nuclear missile is a ‘public good’, providing national security. If the driving force of capitalism is profit, then arms are again not so different from other private goods, but perhaps with one crucial advantage: they may be more functional than civilian goods in that they can reinforce political and economic hegemony and are either rapidly used or rendered obsolete, which guarantees endless demand, thereby helping to absorb surplus. This book adopts the latter approach, in which the driving force of capitalism is profit. The book stands at the junction of defence economics and Marxist economics, examining the effect of military expenditures (milex hereafter) on the rate of profit, an indicator of the health of capitalist economy.

Defence economics is a subfield of economics that studies the causes and consequences of conflicts and military production (e.g. milex).1 The term militarism2 is a wider concept, with social and political roots. In addition to high milex, the term refers to the dominance of military power and values over society and governance, including but not limited to the exaggeration of external and internal threats as a means of justifying a large military and/or high milex, the adoption of aggressive foreign policies and repressive internal security measures, and the extensive use of militarist symbols and procedures3 (Smith, 2009, p. 28). Thus, there are several ways the military influences society, which requires environmental, philosophical, psychological, sociological, and feminist perspectives to fully understand the causes and consequences of the military. Taking an economic perspective, this book employs various quantitative methods to perform a modest task: to examine the effect of milex on economic performance from a Marxist perspective. Although there has been an ever-growing literature on the effect of milex on economic growth, there have been very few studies examining the role of milex on profitability. Therefore, this book aims to fill this gap by providing comprehensive evidence on the mechanisms by which milex affects the rate of profit, thereby aiming to contribute to ‘quantitative Marxism’.

A brief history of military expenditure

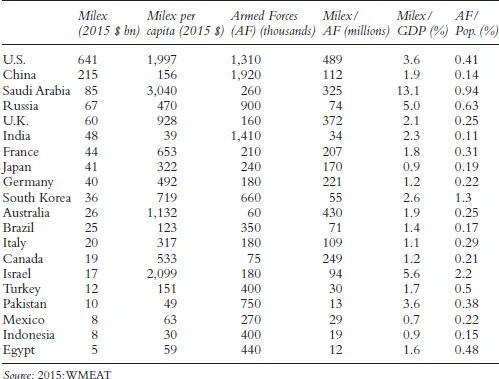

Global milex in 2017 was $1.74 trillion, or about $229 per person per year. As Smith (2009) noted in reference to earlier data, this is a tragic figure when one considers that there are several hundred million people living on less than a dollar a day. In fact, the 10 countries with the highest milex accounted for 73 percent of the total (SIPRI, 2018): the U.S., China, Saudi Arabia, Russia, the U.K., India, France, Japan, Germany, and South Korea. Table 1.1 presents some valuable figures for the top 20 spending countries in 2015, based on the U.S. World Military Expenditures and Arms Transfers (WMEAT).

Table 1.1 shows some important indicators of milex. High milex per capita is notable in the cases of Saudi Arabia, the U.S., Israel, and Australia. Milex per capita shows the cost of milex per person. The ratio of milex to the armed forces may be considered a rough measure of the capital intensity of the military (Smith, 2009, p. 93). The ratio of armed forces to the population shows the proportion of people who serve in the military. It is important to observe the indicators of milex and the military burden (e.g. the share of milex in GDP) together. For instance, although China is the second largest spender, the ratio of milex to GDP is just 1.9 per cent, below several countries with high ratios, such as Saudi Arabia, Israel, Russia, Pakistan, the U.S., South Korea, India, and the U.K.

Table 1.1 Military spending in 2015

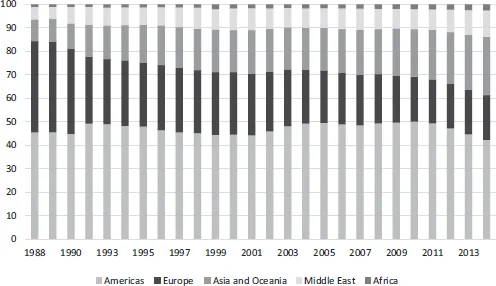

Figure 1.1 shows regional share of milex in total world milex. Whereas the share of the Americas, the highest-spending region, has declined slightly (considering its enormous size), there have been remarkable increases in Asia and Oceania, the Middle East, and Africa, corresponding with a substantial decline in Europe. The share of the Americas declined from 45.5 percent to 42.3 percent from 1988 to 2014. The increase for the same period in Africa was nearly 1.5 times, from 1.1 percent to 2.5 percent. Similarly, the increase in the Middle East was more than two times, from 5.3 percent to 11.2 percent, and in Asia it was about three times, from 9.3 percent to 24.9 percent. These increases corresponded with a significant decline in Europe, from 38.9 percent to 19.1 percent.

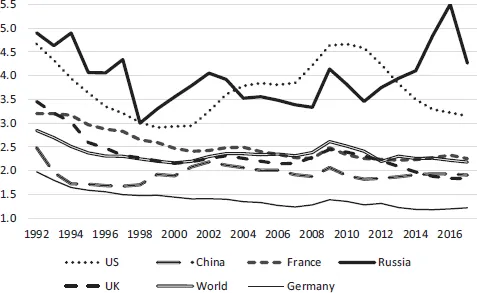

Figure 1.2 shows the share of milex for major countries during the Cold War era. There are two notable patterns. First, while there has been an overall decline in the military burden in the last decade, Russia has sustained its high spending ratio. Second, except for the U.S. and Russia, there has been a steady decline in the military burden in other major countries. Although the end of the superpower conflict led to an initial decline in milex, conflicts in the post–Cold War era became intra rather than interstate (D’Agostino et al., 2016).

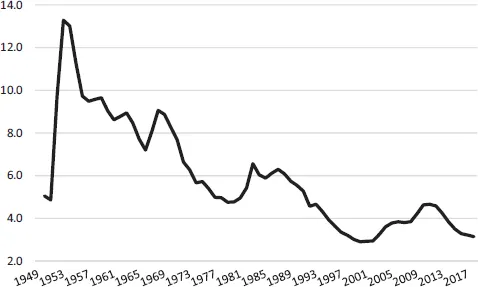

Table 1.1 shows that U.S. milex in 2015 was $641 billion, which is nearly three times that of the second highest spender, China, and larger than the next nine biggest military spenders combined.4Figure 1.3 shows the U.S.’s military burden for 1949–2017.

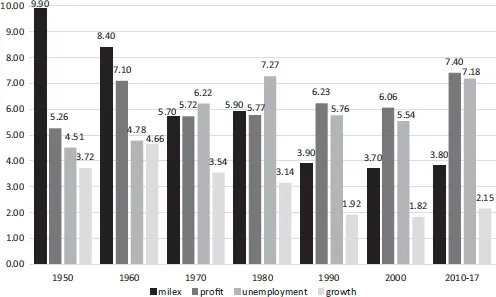

Figure 1.3 shows that milex in the U.S. rose to as high as 13 percent in 1953 due to the Korean War, followed by a steady decline until the Vietnam War. After that, milex declined to 4.8 percent in 1979. This downward trend was broken due to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1980 and the election of President Reagan, which pushed milex to the peak of 6.3 percent in 1986. The end of the Cold War led to a steady and significant decline in milex as a share of GDP, dropping to 2.9 percent in 1999–2000. This was followed by a steady increase throughout the 2000s, triggered by the September 11 attacks and the subsequent global war on terrorism. Currently, milex has again decreased since the 2010s, falling to 3.1 percent in 2017. Figure 1.4 shows this general pattern in terms of average spending over decades along with the other main variables in the study: profit rate, unemployment, and economic growth.

Figure 1.1 Regional share of milex

Figure 1.2 Milex share in GDP – selected countries (%)

Figure 1.3 U.S. milex share in GDP (%)

Profit rates both in the U.S. and other major economies rose in the post–WW II era up until the mid-1960s. This rise was followed by a fall until 1982 when profit rates recovered again during the neo-liberal period. After a short fall from 1997 to 2001, profit rates once again rose in the credit boom up to 2005–6. In the 1970s, there was a substantial transfer of profit from the non-financial to the financial sector in the U.S., which continued at an increasing rate under the full neo-liberal paradigm (Bakir and Campbell, 2013).

A sizeable literature has examined the effect of milex on economic growth and unemployment in the U.S. and other major countries. While there is an evident positive effect of milex on unemployment (Tang et al., 2009), the effect on economic growth is inconclusive. One part of the literature finds a negative effect, suggesting that milex impedes economic growth because it crowds out productive spending, such as public and private investments and education. Another part of literature argues for a positive effect. According to this view, milex leads to fiscal expansion and higher aggregate demand, thereby increasing employment and output if there is spare capacity, while technology-intensive military production may have a spill-over effect on the civilian sector. Overall, the literature provides inconclusive evidence due to various factors, such as degree of utilisation, how milex is financed, and externalities from milex (Dunne et al., 2005, pp. 450–451).

Figure 1.4 U.S. milex share in GDP (decadal averages)

Strategic and economic motives for military expenditure

There are three main economic views regarding conflict (Smith, 2009). First, according to the materialist view, wars between countries as well as civil wars in poor countries result from the battle for natural resources like oil, water, or diamonds. Second, the liberal5 view suggests that free trade and economic integration lead countries to reduce their milex, which in turn promotes peace and prosperity as they avoid conflict spirals and devote more resources to social spending. Wars, on the other hand, cause large budget deficits because of increasing milex and declining tax revenues due to disruptions in trade. The origin of the liberal approach goes back to Immanuel Kant’s view that citizens governed by effective, democratically representative regimes that promote individual freedoms and rights become less willing to sacrifice themselves in military conflicts. Democracies are also less likely to go to war with each other: the so-called democratic peace or peace dividend.6 Third, the mercantilist-Leninist view, on the other hand, can be best summarised by the famous aphorism of Carl von Clausewitz, the 19th-century Prussian general and military theorist, that “war is the continuation of politics by other means”. According to the orthodox Marxist view, however, war is the product of the capitalist system, a product to protect itself because the system must expand its markets. As Luxemburg noted, the direct coercive power provided by the military and the ideological influence of militarism were key mechanisms of primitive accumulation in the history of capitalism (Rowthorn, 1980). War creates additional demand, helps to eradicate stock surpluses, and counteracts the tendency of profit rates to fall.

There are several strategic and economic motives for milex (Smith and Smith, 1983), with three aspects of the strategic requirement for milex in capitalist systems. First, capitalist states must protect the international capitalist system from external threats, such as communism or radical Islamic terrorism. Second, military power is used to sustain the hegemony of core nations over peripheral capitalist countries and to regulate the rivalry between core countries. Third, states use military power (and promote militarism) against internal threats to protect the social order. Core countries also build organic ties with the militaries of peripheral countries by providing (or selling) arms, training, and advisers, making the military in less-developed countries highly functional in terms of guarding and advocating capitalist ideology, even when they are not in government (Smith and Smith, 1983, p. 43). For example, military coups in Chile, Turkey, and several other Latin American countries facilitated radical switches to the neo-liberal model.7 Similarly, after the forcible liberalisation of Arab socialist or Islamic countries, the neo-liberal agenda was achieved by privatising public assets as cheaply as possible, opening domestic markets to foreign companies, and exporting low-priced commodities to Western markets (Galbraith, 2004, p. 299).

External or internal threats are considered major determinants of milex. In this sense, during the Cold War, the key determinant of the milex in both the U.S. and U.S.S.R. was the arms race. In an arms race, both countries spend more but neither can increase their security.8 Arms races also occurred between India and Pakistan, Greece and Turkey, North Korea and South Korea, and China and Taiwan. However, even in the absence of external and internal threats, countries may prefer to have high milex for status reasons because a powerful state is commonly associated with having a strong military. In this sense, the military-industrial complex (MIC) theory offers an institutional perspective to understand milex and conflict. The MIC, a concept popularised by U.S. President Eisenhower, refers to a coalition of vested interests across the bureaucracy, the armed forces, and large arms producer firms. (See Chapter 3 for a detailed discussion.) This symbiotic coalition, which has an autonomous structure within the state, promotes and lobbies for high milex in the name of ‘national security’ by using actual or perceived internal or external threats. In fact, even within the military there is rivalry between the army, navy, and air force for more power and resources, pushing their own agenda regarding new weapons in the case of the U.S. (Smith, 2009, p. 27). At the global level, NATO, a part of the MIC, also favours higher milex.

Economic effect of military expenditure

To analyse the effect of milex on the economy, neoclassical economists use the tools of production possibility frontier (PPF), opportunity cost, and cost-benefit analysis. Basically, the state, a rational actor, tries to maximise the national interest by measuring the marginal benefits and marginal costs of milex.9 The ...