1

Early life

The uneasy social transition in mid-nineteenth-century Maharashtra pivoted on Mumbai, the British power centre, rippling out into the rest of the region. Within its purview came the nearby seaport of Kalyan, about forty miles northeast of Mumbai, once bustling with coastal and maritime trade and legendary for its prosperity. But the town’s fortunes had dropped steadily with the decline of Maratha power in 1818, and were matched by the family of Ganpatrao Joshi, whose ancestors had formerly been rewarded with a great landed estate by the Peshwa. The once stately family mansion was now reduced to dilapidation. The loss of political patronage contingent upon the transfer of power to the British had impoverished the aristocratic Brahmin family, which still enjoyed a high status as the landed gentry of Kalyan.1

Ganpatrao’s kinship network encompassed the erstwhile Maratha power centre, Pune itself, through his marriage to Gangabai after the early death of his first wife, who had left behind a son. Gangabai had spent her childhood with her widowed mother at the house of her maternal uncle, a reputed Ayurvedic physician named Balshastri Mate of Pune, and it was to this house that Gangabai went to deliver her daughter Yamuna, later to be renamed Anandibai. This was unusual in that customarily only the first child was delivered at the mother’s parental house, whereas Yamuna was the fifth of Gangabai’s nine children. Of these only four survived: daughters Kashi, Yamuna, and Sundara, and son Vinayak.2

Born on 31 March 1865, Yamuna was the proverbial ‘unwanted daughter’. The chubby and attractive baby grew up in a largely conventional social milieu, albeit with somewhat reversed parental roles. Instead of being the usual strict and aloof father, Ganpatrao was generally indulgent, while Gangabai proved to be a harsh mother whose lack of affection was compensated for by Yamuna’s maternal grandmother, who was part of the extended family and to whom Yamuna was greatly attached. Under her loving care, which included a nutritious diet unusual for girls, Yamuna grew into a strapping girl who once defeated an older male cousin in a friendly wrestling bout – an achievement which earned her the nickname of malla, or ‘wrestler’.

Influenced up to a point by progressive ideas about women’s education, Ganpatrao enrolled Yamuna in the small school which was run in one section of their large mansion. However, this was probably motivated by a desire to keep her out of mischief, rather than to educate her, as Yamuna was an active and strong-willed child who spent all her time playing games either with the neighbourhood children or by herself. In spite of her half-hearted school attendance, the little girl proved to be bright enough to master reading and writing, much to Ganpatrao’s delight. At a time when a man was discouraged by custom from showing his attachment to his children,3 he was wont to show off her reading skills to his invariably conservative and therefore shocked visitors.

The tensions which circumscribed Yamuna’s relationship with her mother did not stem entirely from the unwelcome disciplinarian maternal duties, but were perhaps rooted in Yamuna’s characteristic obstinacy and obduracy, or her being yet another unwanted daughter, or some other personal frustration which Gangabai usually vented through physical violence. Her harshness seems to have been disproportionate. On one occasion, when Yamuna had failed to return home from school at the usual time and was discovered playing with a girl next door, having missed school altogether, the distraught Gangabai rushed out and dragged her home, abusing and kicking her all the way. That this was not an exceptional outburst born of acute anxiety was later confirmed by the adult Yamuna’s letter in a moment of relived physical and emotional anguish:

My mother never spoke to me affectionately. When she punished me, she was wont to use not just a small rope or thong, but always stones, sticks, and live charcoal. Fortunately my body does not bear any scars, and her severe beatings did not leave me maimed, crippled, or deformed. By the grace of God, my limbs survived intact! But oh! the agony of those memories! I don’t say this as a result of the emotional distancing which comes about with the passage of childhood. Truly she never understood the duties of a mother, nor did I experience the love which a child naturally feels for its mother. This memory hurts me a great deal. A child which harbours fear for its parents cannot possibly feel affection for them, and a child which feels love for its parents does not fear them. Unfortunate indeed is the child which has missed a happy childhood. I feel perfectly certain that, having understood the problem, I would be able to solve it. If I ever have a child myself, I will teach people by my own example how children should be brought up.4

The emotional scar was predictably permanent in an era when a girl’s short-lived childhood passed unnoticed into wifehood and when household duties as part of gender socialisation were transformed without a pause into marital responsibilities, although Yamuna seems to have remained a dutiful daughter all her life.

Perhaps as an escape from this unhappy reality, Yamuna was prone from childhood to occult experiences. Once in a dream she saw a remote ancestor whom she had never seen, and who was identified by the much-impressed Ganpatrao, to whom she narrated the dream the next day. He then seemed to have developed a special respect for Yamuna’s power to have these visions, which were to continue throughout her life.

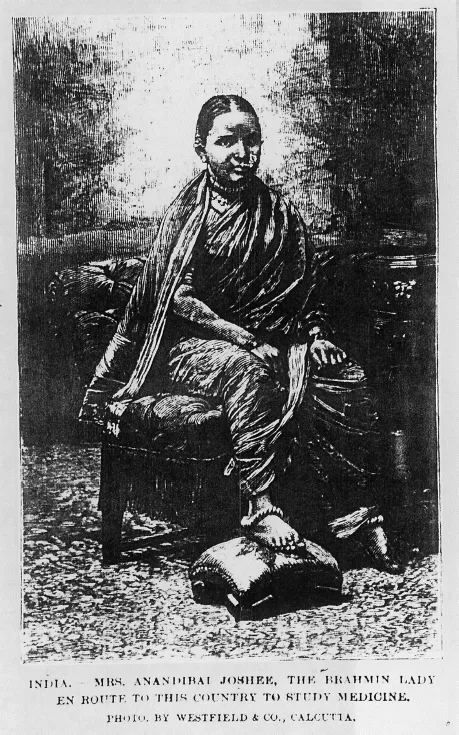

Although possessed of a certain charm, Yamuna was no beauty. Her looks were further affected by an attack of smallpox at the age of five, which left her face slightly scarred, her ‘wheatish’ complexion darkened, and her hearing slightly impaired. Her broad face, with a somewhat flat nose; generous mouth; small deep-set eyes; and large, prominent forehead, was always cheerful and smiling. A short but well-formed figure and long hair improved her appearance. But in the days when a girl’s marriage prospects hinged entirely on fair-skinned good looks – especially among Chitpavans, who cherished the distinctive combination of a fair skin and grey-green eyes – or a large dowry, Yamuna’s frame, which made her old for her age, posed a decided problem. At nine she had already become a liability for her parents in view of the mandatory pre-pubertal marriage for upper-caste girls on pain of social ostracism. Handicapped by his inability to pay a dowry, Ganpatrao started a long and hard search for a suitable groom under considerable social and psychological pressures which affected Yamuna as well.

It was thus considered a stroke of good fortune when an acquaintance brought news of a prospective bridegroom in the person of Mr Gopal Vinayak Joshee, a widower of about twenty-six and postmaster at the nearby port-town of Thane.5 A widower was allowed – in fact enjoined – to marry at any age, while a widow was forbidden remarriage; the bride was in all cases pre-pubertal because of society’s moral anxiety that her budding sexuality would lead her astray unless it was yoked to marriage. A couple mismatched in age hardly raised eyebrows, and it would be a few decades before child marriage and the age of consent became reform issues.

A chance visit brought Gopalrao to the post office at Kalyan, and some women of the Joshi family went to the building to peep at him through the rear door and approved of him. Gopalrao was then invited to ‘view’ the girl at the home of a Brahmin family under Ganpatrao’s patronage, and indicated his cryptic approval without the customary ‘interview’, his only condition being that he should be allowed to educate his bride without interference from her family – a condition unhesitatingly accepted by the desperate Ganpatrao. The betrothal took place immediately and an auspicious date was set for a prompt wedding.

Gopalrao then left for his home town of Sangamner ostensibly to fetch his parents, but in reality to dodge the wedding he had not taken seriously. This incidentally was the first of his many eccentricities that gradually unfolded. When he failed to present himself for the ceremony, much to the chagrin of the bride’s family, the priest who had acted as the mediator was dispatched to start fresh negotiations, and was able to persuade Gopalrao to finalise and appear at the next auspicious date. The marriage was finally performed on 31 March 1874 (which happened to be Yamuna’s ninth birthday) and Miss Yamuna Ganpatrao Joshi became Mrs Anandibai Gopalrao Joshee.6

*

Underneath the twenty-six-year-old Gopalrao Joshee’s (1848–1912) vacillation lay not just his usual eccentricity and inconsiderateness, but also some real cross-pressures and frustrations, especially his ambition to make a mark on the reform scene by educating women and, if possible, by marrying a widow. Interestingly, his personal narrative can be pieced together from various sources, especially from his later and partly autobiographical journalistic writings which friendly newspapers saw fit to publish, such as the English-language Mahratta of Pune.7

As a mature adult he sketched his childhood, with its cross-pressures and shortcomings, which obviously went into the making of a volatile and eccentric personality. By then he had come a long way, socially and emotionally, from his orthodox Brahmin upbringing in the small town – in his view the ‘village’ – of Sangamner, and his obsessive ritualism inspired by his father.

In my boyhood I was very orthodox and superstitious like the rest of the Hindus. My holy thread was so sacred to me … [that if I lost it] I became restless and uneasy as if I had committed a great sin… . I began to fast on the 12th of each fortnight as the day of my favourite deity – Shiva… . Besides this I used to observe two other fasting days. My mother did not like this, but she could not help [it], having no chance to interfere… . If it were not for my father’s devotional life, I would not have been driven to such rigid observances and practices at such an early age.8

Gopalrao offers a vivid description of his appearance on these occasions of fasting and worship: the body smeared with ashes; black beads on his head, neck, and wrists; seated on a tiger skin, burning camphor and incense; waving a platter of lights before the Shiva image, with articles of worship and the requisite flowers and leaves scattered around him. This Hindu orthodoxy was inevitably to clash with the gradually encroaching Westernisation. Like countless similarly situated boys, Gopalrao found his vernacular schooling to be a source of deep inferiority when faced with the confidence bred by a privileged English education:

It was my idea that howsoever learned one was in his own vernacular, he was ignorant if he did not know English.9

How anxious I was to learn [the] ABC of the English tongue, I cannot tell. My energies were exhausted on the acquisition of this new language. Nothing but this was before me. To bespeak and write [English] was my great ambition. I thought I would be a prodigy if I knew that.10

The intensity of the ambition was fuelled by the visit of his old school friend who had gone to Mumbai and learnt English.

He had become a gentleman and I had remained a fool. His expression and style of walk[ing] and stand[ing] were altogether refined. He appeared to me a ‘Bada Sab’ [a high-status man]. Though I was his schoolmate yet I had not the courage to go before him, because I looked like a villager, a jungly [unrefined] fellow. I was full of remorse and mortification… . [and thought of] suicide.11

The feeling of worthlessness was aggravated by his father’s derogatory comparison of young Gopal with this clever and smartly turned out Mumbai friend. Gopal was stung into a resolve to overcome the numerous and obvious difficulties to acquire an English education. But, like most children, he was afraid of speaking to his father and strategically used the mediation of his mother by threatening dire consequences if he was not sent to Pune to learn English. The father, burdened with the responsibility of maintaining a household of about six, finally yielded to pressure and borrowed money to send Gopal to Pune for a year. With a meagre allowance, Gopal could afford only the Mission School in Ravivar Peth, Pune, attended by about four hundred boys. The enormous pressure to do well proved counter-productive; he became sick and returned home. This boyish lack of perseverance was perhaps natural in view of the acute financial pressures, although impulsive behaviour and an inability to take a firm stand continued to characterise him in adult life.

Meanwhile, his burning desire to learn English remained. He approached a relatively affluent older cousin for support and funding, but the cousin transferred the matter to Gopal’s mother-in-law. He had been married at eleven to a girl of five from the Ketkar family of Nashik; now he became ‘a caged son-in-law’ and was forced to submit to constraints and discipline for the first time.12

Earlier, Gopal’s orthodox father had been progressive enough to include his daughter – Gopal’s older sister Mathura – in the Marathi lessons he gave the boy at home. The intelligent girl outshone Gopal in studies, and this had angered him once enough to tear up her books in a fit of envy.13 However, the experience also revealed to him how bright and receptive girls could be, and he later tried to teach his unenthusiastic wife at home, finally prevailing upon his brother-in-law Bapusaheb Ketkar, alias N.G. to continue until she was able to drop him routine letters when he was away. She remained a conventional woman and died early, leaving behind a son who was probably raised by the Ketkars. Gopalrao’s close friendship with Bapusaheb Ketkar long survived his wife’s death.

Armed with an English education from Nashik, Gopalrao first got a job as a subordinate of the Inspector of Post Offices, was later appointed as a clerk at the General Post Office at Mumbai, and subsequently was given independent charge of the post office at Thane. During the mental...