![]()

Chapter 1

Introducing the research

Introduction

When the English Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) (DCSF, 2008) was introduced, the purpose of the curriculum was to support children, from birth to five years, achieve the five Every Child Matters (ECM) outcomes. These were: Be Healthy, Stay Safe, Enjoy and Achieve, Make a Positive Contribution and Achieve Economic Well-being (DfES, 2003:6). In March 2012 the purpose of the EYFS changed to promoting provision that would ensure children are in a state of ‘school readiness’ when they start school (DfE, 2012). When the term ‘school readiness’ was explicitly referred to in the EYFS (DfE, 2012) I was a teacher in a Sure Start Children’s Centre (SSCC). Originally, in 2003, I was employed as the Sure Start Local Programme (SSLP) teacher and became the SSCC teacher when government Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) policies changed. (The historical developments in ECEC provision are discussed in Chapter 2.) Throughout my employment as teacher, I perceived the relationships between the ECEC setting and school personnel as fragile. An independent report, which explored the ECEC practices, confirmed my belief as it highlighted the contributing factors to the fragility of the relationship. These included the differences in ECEC practitioners’ and teachers’ ‘judgements on children’s attainment’ (Ellis, 2013:5) when they start school and ‘competing philosophies and differing interpretations of the EYFS’ (Ellis, 2013:5). Soon after the inclusion of the term ‘school readiness’ in the EYFS (DfE, 2012:2) I observed further tensions in the relationship between the ECEC setting and the school. Noticing the increased tension in this relationship, I was motivated to explore ECEC practitioners’ and teachers’ beliefs about school readiness and the relationships between them during children’s transition to school. As parents share the task of supporting children through the transition with ECEC practitioners and teachers, I believed it important they should be included in my doctoral thesis exploration.

The voice of the child

I made the conscious decision not to include the voices of the children, as I wanted to provide a space for the adults to listen to each other. This decision was not based on the belief that children are not able to contribute to research or that their voices should not be included in the planning for a transition. On the contrary, I view children as partners in the construction of knowledge and culture and as an ECEC teacher I always strove to create democratic learning environments. In practice the team and I designed systems so that children could ‘co-construct the curriculum and learning environment’ (Castletown Team, 2006) by building on their strengths and interests instead of their limitations. I also hold the view that starting school can be an exciting time for children and acknowledge that the transition from ECEC setting to school is a rite of passage for them (Brooker, 2008; Arnold et al., 2007). Becoming a school pupil is one of the ‘landmarks in the process of growing up’ (Brooker, 2008:27).

I am also aware that many of the children are familiar with the expectations of being a school pupil. I recall part of a conversation with Jasmine during a research visit to the ECEC setting (research journal 21st May 2013).

JASMINE: What are you doing here?

RESEARCHER: I am finding out about starting school.

JASMINE: I am going to start school in September. I am going to be a big girl, like my sister, have a book bag and learn to read.

Starting school

Parents generally share their children’s enthusiasm and are keen that their children adjust quickly to school and succeed within it (Whalley, 2001). Despite children’s excitement and the positive intentions of parents, starting school can be a difficult time for both. Research findings have highlighted that this transition can influence the child’s attitudes to school and school learning, which can last throughout their school career (Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 2000; Margetts, 2009). The understanding that the transition to school is a key point during children’s early years and can influence children’s educational outcomes (Educational Transitions and Change (ECT) Research Group, 2011) has led to global interest amongst politicians, academics and leaders in education. The inclusion of the term school readiness in the Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition’s revised EYFS (DfE, 2012), is evidence of the English politicians’ acknowledgement that starting school is a key experience in young children’s lives and education trajectory. From this perspective, it is likely that these politicians hold the belief that if children are ‘school ready’ they are more likely to have a successful transition to school.

In contrast, from an ecological perspective it is viewed that a healthy ecology, with supportive linkages between the settings in the mesosystem (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), will support the children’s transition to school (Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 2000). In a context where respectful relationships are established between the parents, ECEC practitioners and teachers (Gonzalez, 2005), the linkages in the mesosystem will be strengthened. The qualities of these respectful relationships are ‘mutual trust, positive orientation, goal consensus and a balance of power’ (Bronfenbrenner, 1979:216). Such relationships enable those in the relationship to communicate and share knowledge about children and their experiences. Sharing and using the information is likely to limit any differences between the home, ECEC setting and school. The reflections between the home, ECEC setting and school are likely to support the children’s transition to school. This perspective shifts the emphasis of ‘readying the child for school’ to the relationships between those supporting the child through the transition.

The research problem and questions

A challenge for those implementing the EYFS (DfE, 2012, 2017) framework and preparing children for school is that school readiness and associated terms are difficult to define and measure (McDowall Clark, 2017; Graue, 2006; Kagan & Rigby, 2003). Consequently, parents, ECEC practitioners and teachers are likely to have different beliefs and expectations of the term. Whilst definitions and expectations may vary, it is the political view that ‘good parenting’ and ‘high quality ECEC learning’ experiences contribute to children’s readiness for school (DfE, 2012). If children are viewed as not progressing in their school learning soon after they start, it can appear to teachers that children were not ready for school (WaveTrust, 2013). Such assessments can position parents, whose children are regarded as not ready for school, as ‘not good parents’ who require support to prepare their children to be ready for school (Field, 2010). If children had attended an ECEC setting, blame can also be apportioned to ECEC practitioners, as they also had not prepared the children for school (McDowall Clark, 2017). These views are likely to influence the relationships between those preparing and supporting children when starting school.

The increasing tensions in relationships between the school and ECEC setting since the changes to the EYFS (DfE, 2012) led me to ask the research questions:

- What are parents’, ECEC practitioners’ and teachers’ beliefs about school readiness and their roles in preparing children to be in the state of school readiness?

- What are the qualities of the relationships and interactions between parents, ECEC practitioners and teachers and how do these change as they prepare and support children during the transition to school?

- What opportunities are there to co-construct beliefs of the child, learning and each other’s role in the process during the transition?

The research approach

My understanding of knowledge construction align with socio-cultural theories (Rogoff, 2003). I believe people are social actors who as individuals, and with the groups to which they belong, construct knowledge and their beliefs in their historical and cultural context (Benzies & Allen, 2001). Therefore, when exploring participants’ beliefs and relationships I was keen to retain ‘the holistic and meaningful characteristics of real-life events’ (Yin, 2009:3). Thus, I drew upon features of case study research (Yin, 2009). Through the qualitative data generated I explored the beliefs held and the relationships between participants during the transition from ECEC settings to the school reception class.

The flexible design of the case study enabled me to respond to an issue that emerged, at a local level, during the research process. Initially, the case study comprised parents, ECEC practitioners, and teachers from the context I had worked. After generating the data, it became apparent, when evaluating the ‘sampling adequacy’ (Robson, 2011:154), that the limited participation of teachers had resulted in insufficient data representing their beliefs and experiences. Another case was sought, which led to the case study research consisting of two cases in two different geographical communities. Each case comprises of parents, ECEC practitioners and teachers. The relationships between the parents, ECEC practitioners and teachers and their beliefs about school readiness were the ‘units of analysis’ (Grünbaum, 2007:88) rather than the participants themselves.

Introducing the participants and contexts

Whilst each case was located in a different geographical community the neighbourhoods of each case were similar. Both were white working-class communities in the south west of England; the Indices of Multiple Deprivation states the Castleton neighbourhood is in one of the 5% of most deprived areas in England, and Townmouth is in the bottom 10% (Southward County Council and Southward NHS, 2011). Residents may therefore experience many of the issues related to poverty, such as poor mental health, addiction, isolation and so forth.

In both cases the ECEC setting and a primary school shared the same site. ECEC practitioners, parents and children would walk across the school site to enter the ECEC setting. At the time of the data collection both ECEC settings were part of a SSCC. The ECEC practitioners were line-managed by the SSCC leaders; the reception teachers were line-managed by the school head-teachers. In both cases some of the ECEC practitioners had worked in the preschools prior to the ECEC settings becoming part of the SSCC. To work towards equal representation from each of the groups, reception teachers from other schools, which the children moved to, were invited to take part in the research.

Castleton participants

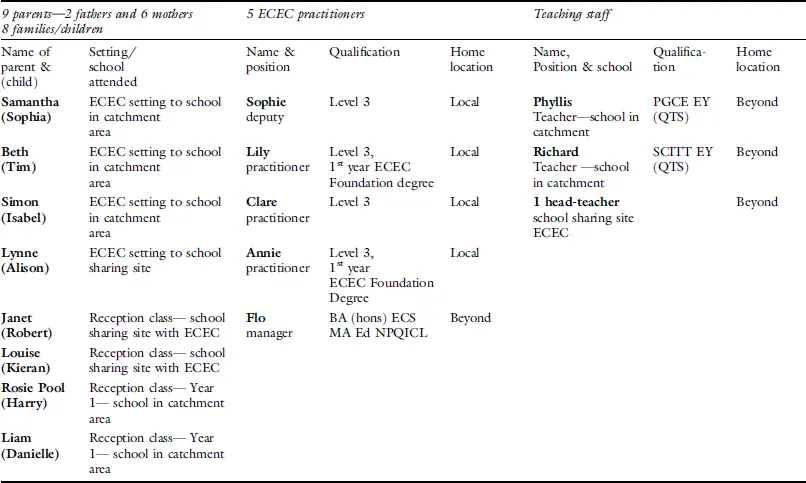

Table 1.1 introduces the Castleton case participants.

Table 1.1 Castleton participants

All parents and ECEC practitioners except the ECEC setting manager lived in the local neighbourhood. The ECEC manager, teachers and school leaders lived beyond the local neighbourhood. The ECEC setting manager had the Level 7 Masters in Education and the National Professional Qualification for Integrated Centres leadership qualification (NPQICL), all ECEC practitioners had a childcare qualification (level 3) and two of these ECEC practitioners were in...