- 186 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Literacy of Play and Innovation provides a portrait of what innovative education looks like from a literacy perspective. Through an in-depth case study of a "maker" school's innovative design—in particular, of four early childhood educator's classrooms—this book demonstrates that children's inspiration, curiosity, and creativity is a direct result of the school environment. Presenting a unique, data-driven model of literacy, play, and innovation taking the maker movement beyond STEM education, this book helps readers understand literacy learning through making and the creative approaches embedded in early literacy classroom practices.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Literacy of Play and Innovation by Christiane Wood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

New Possibilities: The Potential of Makerspaces as Literacy—Play Learning Environments

This space is loud.

Children are talking, singing, and making muddled noises …

This rhythm and melody could be the sound of thinking, imagination, creativity, whimsy, or of an inventor. Some children are gathering materials of cardboard, tape, glue, and fasteners.

Others are tinkering—trying out their cardboard creations,

some only to find that the creation is not strong enough to sustain user testing or usability. Failure? Not at all—try and try again.

It is the process of iteration, one step in the design process.

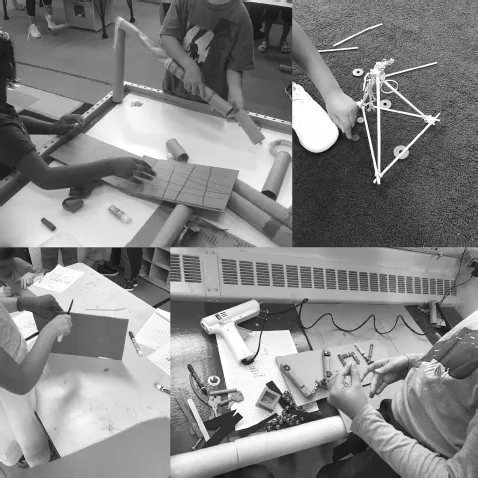

At first glance this early childhood classroom space may seem chaotic—but to the children it is a playful, meaning-making environment embodied with literate possibilities. The preceding description is taken from observational field notes in the Innovators Workshop, Bricolage Academy’s makerspace (Figure 1.1). In this space, children make things using material resources at hand such as cardboard, tape, paper, LEGOs, wires, circuits, and wood. In this makerspace, kindergarten, first, and second grade children plan, explore, tinker, design, iterate, and create things. Viewed as bricoleurs—tinkerers—children use the resources around them to build and create pulleys, catapults, marble walls, robots, cardboard creations, stories, songs, and drawings, among many other creative and imaginative things.

This makerspace is purposefully designed to spark children’s interest in problem creation and problem solving. It is a social space that encourages young children to question and wonder, engage in whimsical play, tinkering, and hard work, all to explore and learn about the world around them. Using predictable instructional routines and guided-scaffolded instruction, educators contribute to children’s content knowledge, provide children with opportunities to use a variety of tools and materials, and allow time and space for children to engage in playful exploration and experimentation. Through playful experimentation “tinkering” children begin to build their literacies, gain conceptual understandings, engage in deep content knowledge learning, and expand their collaboration and communication skills. In this makerspace, all children are viewed as bricoleurs—tinkerers who have the opportunity to demonstrate their cleverness as a learner, an expert, a meaning maker, and innovator in multimodal ways. Tinkering in the context of this book is literacy and can be defined as a multimodal, playful, exploratory, iterative style of making meaning. Tinkering helps us to understand the process by which children recombine elements to create new functions, and is the process through which children use and combine resources they have “at hand” as a means of finding workable, imperfect, approaches to a variety of problems or opportunities. Tinkering for children, then, is a process by which they individually and collaboratively use their cultural knowledge, resources, imagination, and objects around them to incorporate ideas and meaning making. I identify tinkering as a new literacy because the processes of designing include, and result in, multimodal forms of meaning making.

Figure 1.1 Children Making in the Innovator’s Workshop—Bricolage Academy’s Makerspace

Meaningful Literacies, Play, and New Pathways of Academic Achievement

Empowering children to expand their understanding of the world around them begins with new pathways of academic achievement. Literacy is not only essential to children’s personal achievement but it is also necessary for school and community success. Literacies embedded in every aspect of children’s education impact not only school cultures and the children and teachers who make up the classroom environment, but they also have an impact on the cultural, economic, and political factors that influence literacy development and attainment in the community at large. Engaging young children with meaningful literacies and opportunities to play positions them to become readers of the world around them as members of a community. For young children, literacy and play are the foundations of all learning and for this reason, understanding how literacy and play intersect with design and makerspaces becomes important as we explore the pedagogical value of making and creating cultures of innovation. There is a need to learn how children learn to make, and make to learn in early childhood learning environments (Peppler, Halverson, & Kafai, 2016).

Research on New Literacies (New London Group, 1996) in particular provides an interdisciplinary approach through multiple lenses and areas of inquiry to help understand and inform phenomena in contemporary classrooms. Currently, makerspaces and making and STEM activities are part of a growing trend in formal educational learning environments. Examining makerspace environments in formal school contexts is necessary to improve our understanding of what types of literacies children engage in and how literacy teaching and learning happens in these spaces. It is important to build this area of inquiry by examining literacy from both teacher and students’ perspectives. Literacy teaching and learning in classroom makerspace contexts includes both teachers’ and children’s knowing “which forms and functions of literacy support one’s purpose” (Coiro, Knobel, Lankshear, & Leu, 2008 p. 5). Therefore, examining the what and how related to literacy pedagogy and children’s literacy enactments in makerspace contexts becomes increasingly important.

The Literacy of Play and Innovation: Children as Makers, examines literacy and play as a foundation for innovation and equity in early childhood classrooms and makerspace contexts. The purpose of this book is to establish the connections between teachers’ pedagogical practices that promote literacy, equity, and innovation with the complexity of children’s literacy-play enactments as they make in classroom and makerspace environments. Literacy and play are well established in the research literature as a pathway to support learning for all children. This research draws upon various theoretical perspectives including sociocultural theories of literacy, multiliteracies, play, and constructionism to provide a diverse lens regarding our understandings of literacies from multiple perspectives. One aim of this book is to begin constructing a foundation for the important development of theories, models, and methods that will allow us to study the new and complex literacies in early childhood makerspace contexts. The questions that guide the research behind this book are: How does a school create a culture of innovation and equity that promotes skills, dispositions, and mindsets to empower all children? What does an innovative school context look like? How might we use literacy in early childhood classrooms as a foundation to promote and spark curiosity, encourage children to wonder, engage children in whimsical play and help guide and transform children’s clever ideas into something never thought possible? What literacy pedagogical practices guide the integration of design and innovation in classroom contexts? How do teachers create classroom environments that encourage play and innovation? What types of literacy are young children enacting when they play/work in classroom and makerspace environments? and, What do children do when they play/work in environments that support making?

This research provides a starting point for us to understand how classroom literacy practices coincide with the promise of the maker movement in ensuring all children have opportunities to become innovators, as well as uncover the potential of makerspaces as equitable literacy learning environments. The end goal is to provide readers with an understanding of where these ideas started and a vision for the future.

Background of the Research Project

To current concerns about our increasingly diverse student population and about the school’s effectiveness in serving those students, we collectively declare through vivid example the need for and the power of story.

(Dyson & Genishi, 1994, p. 6)

This book originated from my dissertation research of a case study regarding literacy, play and innovation. Echoing the preceding Dyson and Genishi (1994) quote, as an educator who has worked in urban early childhood, elementary, and middle school settings, my experiences working with diverse populations of teachers and children sent me on a quest to find ways in which marginalized children could benefit, learn, and be engaged in their education with hope to improve their future. It is my own reflective practice as an educator that leads me to think deeply about the realities of children’s and teachers’ lived experiences and find ways to improve literacy teaching and learning.

Inspired by the works of Dyson and Genishi (2009), Hassett (2008), and Wohlwend (2008) related to play and literacy; Berland, Martin, Benton, Petrick, and Davis (2013) and Resnick and Rosenbaum’s (2013) research on tinkering; and the work of Peppler et al. (2016) related to makerspaces, I set out to find a school that valued literacy, play, and new approaches to educating socioeconomically and culturally diverse populations of young children. Bricolage Academy’s mission and vision aligned with the goals of my dissertation study, and after reflecting on the original study I realized more in-depth research was necessary to uncover how classroom literacy practices and children’s literacy understandings operate within makerspace contexts, as well as the potential of makerspaces in early childhood contexts to function as equitable learning environments. For these reasons, I continued to research the primary classroom and makerspace contexts two years beyond my dissertation study. Focusing on a socioeconomically and culturally diverse population of young urban children, over the course of three academic years, I explored the multiple functions of literacy, children’s play, and making in kindergarten, first grade, second grade, and the makerspace learning contexts.

Setting

Bricolage Academy is a K–5 urban public charter elementary school located in the Bayou St. John near mid-city New Orleans, Louisiana. As a public charter school, families have the option to choose Bricolage Academy through a unified application processes put in place by the Orleans Parish School Board and Recovery School District. The unified application process is used to ensure access and school choice to all families and children citywide. This process has diversified the school’s demographics as Bricolage Academy attracts both White and African American children who live in neighborhoods throughout the greater New Orleans area, and are representative of both middle and upper-middle class socioeconomic status (SES) families, as well as low-income SES families.

As a recent addition to the New Orleans public school system, Bricolage Academy is embarking on its fifth year. Adding a new grade level each year, Bricolage Academy aims to become a kindergarten through 12th grade school over time. When I began to visit, Bricolage Academy was in its second year of existence and served kindergarten and first grade children. At that time, the school was located in a synagogue in Uptown, New Orleans. During the first year of the study, 150 students were enrolled: 43% girls; 57% boys; 48% White; 42% African American; 5% Hispanic; 2% Pacific Islander/Asian; 3% Multiethnic. Approximately 46% of all students were classified as economically disadvantaged. In the fall of the second year of the study, Bricolage Academy moved across town to Bayou St. John to occupy a former Catholic school building. During the second year, Bricolage Academy served children in grades K–2 and grew to 240 students. The population included approximately 43% girls; 57% boys; 51.3% White; 39% African American; 3.4% Hispanic; 3.8% Multiethnic; 2.1% Pacific Islander/Asian; and .04% Native American. Approximately 46% of all students are economically disadvantaged. In the third year, Bricolage Academy served 331 students in grades K–3. The population included approximately 41.1% girls; 58.9% boys; 51.1% White; 37.2% African American; 4.8% Hispanic; and 4.8% Multi-racial. On average, 40% of students qualify for free and reduced lunch.

Participants

The research participants in this study include Bricolage Academy’s CEO, Mr. Densen; the elementary school principal, Ms. Murphey; four teachers; one associate teacher; and the children in the participating teachers’ classrooms. The teachers in this study include Ms. Magnolia, the kindergarten teacher; Ms. Dauphine, the first grade teacher; Ms. Jackson, the second grade teacher; and the makerspace teachers—lead teacher, Mr. Toulouse; and associate teacher, Ms. Bienville. It is important to note that the names of the teacher participants and children have been changed. The school, geographical location, and administrators have been identified with permission.

Methodology

Using case study methodology (Yin, 2013), I spent extended periods of time in Ms. Magnolia’s kindergarten, Ms. Dauphine’s first grade, and Ms. Jackson’s second-grade classrooms during reading and writing workshop to capture each teachers’ pedagogical practices and observe the literacy enactments and play children engaged in during literacy time. I also spent extended amounts of time in Mr. Toulouse’s Innovator’s Workshop, Bricolage Academy’s makerspace classroom. I explored the multiple functions of literacy and was particularly interested in uncovering the ways that design thinking is implicitly or explicitly embedded in literacy pedagogical practices, children’s play, and how classroom environments are created to promote equity and access for all children to learn new skills, strategies, and dispositions while shaping a sociocultural message that all children are makers and can realize their individual potential through making.

The emphasis of the bounded case study (Creswell, 2013; Merriam, 1998; Stake, 2005) on historical economic and cultural forces allowed me to provide a detailed account of the children’s and teachers’ social activities, experiences, and meaning making. It also allowed me to gain understanding of the phenomena of literacy enactments through play, tinkering, and making. This research design helped me to understand significant characteristics that make Bricolage Academy unique as an elementary school. Over time, design and making became a natural part of the kindergarten, first, and second grade classroom environments, and in the Innovators Workshop. I was able to capture the details of pedagogical practices, meaningful interactions, and activities. According to Dyson and Genishi (2005), “the aim of such studies is not to establish relationships between variables (as in experimental studies) but, rather, to see what some phenomenon means as it is socially enacted within a particular case” (p. 10). School and classroom environments have their own culture that shapes behaviors and experiences as well as influences the way individuals generate meaning and make sense of their world. This case study methodology has helped me to gain other perspectives and to uncover the process through which the participants enact language and literacy and how teaching and learning happen through the flow of social participation (Dyson & Genishi, 2005).

I used a mix of data sources including field notes, digital photographs, video recordings, audio recordings, semi-structured interviews, classroom mappings, and artifacts (e.g., student work/productions, lesson plans, newsletters). The case studies were member-checked by the educators and every effort was made to accurately portray what they did.

To analyze the data, I looked to sociocultural theory as a tool to analyze the design of the school context and curriculum. This helped me to understand how Bricolage built off of the historical underpinnings and theories of play and early childhood literacy environments in the overall school design. Next, I looked to new literacy studies; specifically, the pedagogy of multiliteracies (New London Group, 1996), to interpret data gathered from observations during reading and writing workshop. I used the pedagogy of multiliteracies to guide my understanding of how teachers use available designs, designing, and the redesigned in their classroom literacy practice. I looked to constructionist theory (Papert, 1991) to examine the design of the learning environment in the makerspace, as well as to interpret children’s making and the artifacts they created. Finally, I looked to play theory drawing upon Bruner’s (1996) enactive, iconic, and symbolic modes of representation, to analyze the data that aligned with children’s play in the classroom contexts.

Children in our current globalized society require competence in a range of meaning making systems. These new literacies include processes of design and innovation, and there is an increasing need to transform inequitable distributions of literacies through new pedagogies that not only recognize making and design as forms of literacy, but also recognize the challenge to promote equity in the classroom. Looking through an early childhood lens, this research supports the idea that classrooms and makerspaces closely follow the literacy play-based curriculums imagined by educational theorists such as Froebel, Dewey, Montessori, Reggio-Emilio,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction: New Possibilities: The Potential of Makerspaces as Literacy—Play Learning Environments

- 2 The Spark of Mindful Design: Envisioning Equity in a Culture of Innovation

- 3 The Wonderings of the Krewe

- 4 The Whimsy of the Maker

- 5 The Cleverness of Innovation

- 6 Literacy for the Bricoleur

- Conclusion: Three Points of Access: Implications for Pedagogical Practices and Instructional Activities

- Appendix: Examples of Children’s Animal Prototypes

- Index