1 Managing Attachment

Developing a Unified Framework for Attachment in the Workplace

Successful organizations evolve. Today, evolution happens at a blistering pace. The workplace seems to change daily with new technology, while innovative business models and disruptive competition create pressures from all sides. An increasingly diverse workforce confronts a multitude of organizational demands that must be met simultaneously or the organizational objective slips from successful to survival. Each small shift in the workplace adds new challenges, requiring larger shifts in the organizational landscape. Collectively, these issues create real existential pressures on organizations.

At the same time, organizational leaders report that making these kind of evolutionary steps, or even incremental steps, is more difficult than ever. Why? Why do organizations recognize the pressing need for growth and development, but struggle to evolve? Leaders at all levels ask the same question—What is keeping my organization from moving forward?

It appears as if there is a factor inherent in organizations that restricts the organization’s ability to adapt and thrive. There is—it is the People. No matter how fast a business wants to move, it can only move as fast as the people contributing to the business. Moreover, the behavior of people is THE critical element in determining organizational success. In order to move organizations forward, leaders must understand their employees and what creates and maintains the connection between employees and the organization. That is what this book is about.

In the development of our human nature what seems most important is the hereditary origins of those tendencies that serve to bind us together into groups, to form networks, to give us an affinity for those who are similar to our group and a suspicion of those who are different, to be comforted and proud of familiar relationships, to cooperate and collaborate with group members, to give and receive favors, and to exchange information. These were among the factors necessary to build cohesiveness, and “are among the absolute universals of human nature” (Wilson, 2012, l. 895).

From our earliest beginnings, human survival was based on our “attachment” to a group. This proved to be a protective adaptation, providing security to individuals living in a difficult and often dangerous environment. It was under these conditions that human nature developed, and it is from this remote past that our instincts, our traditions, and our beliefs evolved. These very qualities are so deeply embedded in our natures they persist in our minds today. The influence undoubtedly has both direct and indirect relationship on the evolving organizational culture (Sanford, 1987). The bonding that led to group formation was a protective adaptation of individuals living in a dangerous environment. We are the products of that environment. We will explore these issues further in Chapter 2.

Many leaders look at workplace engagement and employee satisfaction as signals, but there are deeper roots that create workplace bonds—the bonds that we naturally make with other people, but also with organizations and with our working environment. These bonds are called attachments. Attachment resides within the brain of each person and connects us to others, to the world around us, and to the organizations within which we work. The bottom line is, attachments are a biological response driven by the unique instincts of each individual to find tangible or intangible objects to “lean on” for support. In a best-case scenario, as infants, it enhances our survival; as children and adolescents it aids in the development of our independence; and as adults it provides us with the security we need to stretch our abilities and creativity.

Attachments are of critical importance to organizational health. Attachment behavior represents a need for individuals to maintain proximity to a specific object. This object can be a physical (such as a leader or a technology) or it can be an abstract concept (such as a mission or creed). With the removal of the object or a threat to one of these objects, organizations unintentionally trigger an attachment response within individuals. This response is the unwillingness of the individual to lose proximity to the object. It explains why some people succeed in an organization and others do not. Why leaders connect with certain team members, but not others. Attachments serve as the foundation on which organizational culture is built. Attachment behavior describes why it can be so hard for individuals to adapt to change, but also holds the key to making change more effective.

If organizational evolution is the goal, effective attachments represent the critical path to success. Attachments can be leveraged to drive organizational evolution, but attachments can also set roadblocks and barriers that hinder change. As leaders set out to improve organizations, they are not changing a singular entity, but rather they are involving the entire set of individuals who collectively comprise the organization. Each individual is going through their own invisible version of attachment struggle, and the behaviors associated with this struggle are the real reason an organization will either succeed or fail, especially when dealing with change initiatives.

This book suggests a new way of understanding attachment as an influential component and a powerful tool for managing organizations in our ever-shifting organizational landscape. Historically, much of the work around attachment explores parent-child relationships, but this book introduces a collective view involving adults in the workplace. By taking the view of a single employee’s attachment behavior and viewing this effect as a collective across the organization, we demonstrate the complexity and the nuance of attachment in the workplace and also the opportunity inherent for leaders to build more effective organizations.

What Is Attachment?

The attachment process is most commonly associated with children. Attachment behavior is an instinctive part of our species’ nature that begins in early infancy and is complemented by the protective behavior of the mother. Attachment behavior is mediated by a system of neurophysiological processes that in the course of development are transformed into a series of internal working models about others, the self, attachment objects, and the world that surrounds the child. As infants move away from birth, they begin to experience an attachment to their parent, and this drive to form attachments follows them throughout their lives

Although much of Bowlby’s work focused on mother/child attachments, he went to considerable effort to emphasize the role and different nature of attachments in adults (Bowlby, 1969, 1980). Bowlby’s beliefs that adult attachments were an important part of the adult experience is well documented; however, their attachments are focused differently and in more directions. While research on adult attachments was slow in its development, it is now actively proceeding in many directions (Weiss, 1994).

Noer (1993) was one of the first to look at this space with his work on “survivor’s syndrome”. This detailed the experiences of those left in the workplace after many of their co-employees had been furloughed or “let go”. Harvey (1999) followed this with a history of the work by Spitz and Wolfe in Romanian orphanages. He used their work to describe the symptoms of loss in organizations as the “Anaclitic Depression Blues”. Further work in this area was initiated by Grady (2005), and continues in the works of Grady and Grady (2008, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2017) and Grady. (2014).

The impact of loss was acknowledged by Bowlby (1980), but with the emphasis on the possible benefits of a healthy recovery (Bretherton, 1992). “It is a characteristic of the mentally healthy person that he can bear this phase of depression and disorganization and emerge from it … with behavior, thoughts and feelings … reorganized for interactions of a new sort” (Bowlby, 1980, p. 245–246). Grady and Grady (2012, 2017) reaffirm this link between organizational change as loss, resultant instability, and a period of grieving. When handled appropriately by organizational leadership, this grieving process can lead to individual renewal and potential for growth in the organization.

Therefore, adult attachment can now be considered the stable tendency of an individual to make substantial efforts to seek and maintain proximity to and contact with one or a few specific individuals or objects that provide the subjective potential for physical and/or psychological safety and security. This “stable tendency is regulated by internal working models of attachment … built from the individuals’ experience in his or her interpersonal world” (Berman & Sperling, 1994, p. 8). Now living in the 21st century,

attachment figures in adult life need not be protective figures, but rather they can be seen as fostering the attached individual’s own capacity for mastering challenge… [today] the role of the attachment behavior system require us to examine the role of secure base … and their connections to attachment representations.

(Crowell & Treboux, 1995, p. 297)

Attachment in the Workplace

The early attachments found in infancy and childhood evolve into more complex forms of attachment. Adolescent attachments may include relatives, teachers, supervisors, leaders or idealized figures; and in adults, these and a variety of other groups, objects, locations, cultural ideals, symbols, and artefacts become attachments.

Once an attachment is formed it becomes an important element in the person’s mental models which in turn plays a major role in the person’s social-behavioral system. These behavioral systems may be positive or negative depending on how the person’s early experiences have played a determining role in the nature of their attachment. An individual’s approach to attachment is called an Attachment Style. At a minimum, there are two attachment styles: secure and insecure. However, we prefer a more nuanced four-style attachment approach described by Scrima, Rioux, and DiStefano (2017). This approach describes these attachment styles as secure, preoccupied, dismissive, and fearful.

Research confirms that workplace attachment style in an individual is similar to their adult attachment style. The research also supports classifying workplace bonds as attachment bonds and provides a connection between adult and workplace attachment styles (Scrima, Rioux, & DiStefano, 2017). These attachment styles remain consistent for individuals, but vary as the individual interacts with organizations.

Some organizations may attract certain personalities because of a natural connection between an employee’s attachment style and the characteristics of the organization (Scrima, DiStefano, Guarnaccia, & Lorito, 2015). Conversely, some organizations may inadvertently attract individuals whose attachment style does not support the organization’s effectiveness. Of course, there is also a scenario where the individual is well aligned until the organization makes a change. Given the important role that attachment plays in supporting an individual employee in an organization, it suggests that it would be beneficial if organizational leaders and HR practitioners enhanced their understanding of attachment styles.

Attachment Realms in the Workplace

Attachment starts in the behavioral systems and instinctual responses in the brain of each person. This leads to the creation of a unique attachment style that is impacted by many factors around the individual. There is an entire ecosystem of activity happening around each person that either supports attachment and connection or creates tension and disconnection. These factors impact not only whether a person creates attachments, but also how individuals create attachments.

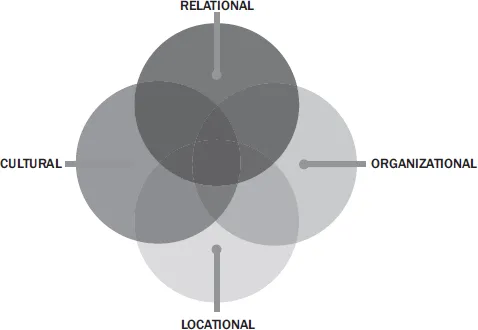

We break these factors of the ecosystem into four realms of attachment. Each individual creates connections (or may avoid connections) with an organization within one or more of these four realms. The four realms are relational, organizational, locational, and cultural. Within an organization an individual’s attachment objects can be positioned in one or more of these realms, some of which may be formed across more than one realm. For example, an employee in an organization may have an attachment to someone in leadership. This would be both a relational and an organizational attachment and is depicted by the area of overlap exclusive to the relational and organizational spheres in Figure 1.1. This figure is also a visual representation of these four realms and their relationship to today’s workplace. It provides an image of the complex and possible overlapping nature of attachments generated by an employee’s brain. The characteristics of these realms are provided next in some detail in preparation for their use later in separate chapters.

The relational realm of attachments involves those formed with other people. Relational attachments evolve within the individual beginning in infancy and follow them throughout life. The relational realm moves with the individual into the workplace and determines their ability to form relational attachments to organizational leaders, supervisors, work groups, and co-workers. (The non-overlapping area of the relational sphere indicates personal attachments that are not related to the organization). The relational realm has potentially profound implications for the efficiency and commitment of the workforce. Some employees create such strong attachments with individual leaders that to the employee the leader is the organization and without the leader the employee loses connection to the organization. However, not all individuals form relational attachments easily. Some adults with different attachment styles or attachment preferences may tend to move away from any or all relational attachments.

Figure 1.1Four Realms of Attachment

Relational features are an important factor in determining the quality of the work life within an organization. Attachment theory, and more specifically attachment styles, provides an interesting source of information as relates to personnel performance, well-being, and development. For example, employees with secure attachment styles are more willing to form quality relationships, are more positive towards their work, and express fewer anxieties. In addition to a secure attachment style, there are also preoccupied, dismissive, and fearful attachment styles. Those with preoccupied attachment styles are less performance oriented, express fear of rejection, and are insecure with respect to their performance. Personnel with dismissive attachment styles are more task focused, tend to avoid relationship building, and less satisfied than those who are securely attached. Personnel with fearful attachment styles tend to be distrustful, hypervigilant, and self-protective (Boatwright et al., 2010). Distinction between these individuals can be assessed through the use of the Attachment Style Index (ASI) (Grady & Noakes, 2018).

The organizational realm represents the attachments that an employee makes with the organization. These can be relational, but may also be associated with other elements of the organization. This could include structural elements, such as the routines and rigors of the organization’s process (think military). It could also be an attachment to the product produced by the organization. Often people want to work for a company because they enjoy the products from that company (such as Apple). There are also many subtle and symbolic qualities such as artefacts, images, and reputation within the organization.

However, organizational attachments can be less tangible; for example they...