![]()

1 A tale of two saints

The politics of blasphemy in Pakistan

In August 2015, I was at the end of my research trip to Pakistan, where I had been immersed in the details of dozens of cases of blasphemy. The trip had taken an emotional toll on me: I had grown up hearing stories about the compassion and mercy shown by the Prophet to his enemies, and could not square that with so many cases of obvious injustice committed in the name of protecting his honor. On a whim, I decided to visit the tomb of Illum-ud-Din (1908–1929) in Miani Sahib, a large graveyard in the middle of Lahore. Like hundreds of other shrines in the Indian subcontinent, the path to the grave of Illum-ud-Din is lined with stalls selling the necessary accoutrements for visiting the saints – rose petals, garlands, and incense sticks. Illum-ud-Din’s tomb looked like many other such shrines dotted along the subcontinent, except that this one prominently displayed a copy of the deceased’s arrest report for murder, and newspaper clippings discussing his trial. Illum-ud-Din was a 19-year-old carpenter who killed a Hindu publisher, Mahashay Rajpal, for publishing a book called Rangila Rasul.1 By paying for this crime with his life, Illum-ud-Din became a shaheed (martyr) for the cause of Namoos-e-Risala (the honor of the Prophet). There are a dozen hagiographies published in Urdu lionizing Illum-ud-Din as both a ghazi (warrior) and a shaheed (martyr).2

In January 2017, I found myself on the road to another gravesite, ostensibly that of another saint, Mumtaz Qadri. In 2011, Qadri assassinated Salman Taseer, the Governor of Punjab, for the supposed crime of dishonoring the Prophet Muhammad by advocating the reform of blasphemy laws. Qadri was in turn executed for murder in 2016, but he received widespread support for his action. Salman Taseer is perhaps the most famous target of the vigilante terror stemming from the blasphemy laws in Pakistan, but he was not its first or last casualty. I approached Qadri’s grave with some reservations: for over two years I had been examining the devastated lives of numerous victims of Pakistan’s blasphemy laws, and I felt that visiting the grave of a perpetrator of this violence might be disrespectful to them. However, my misgivings morphed into curiosity when I saw the scores of people who had come to honor what was, from their perspective, the shrine of an ashiq-e-Rasool (devotee of the Prophet), and were listening solemnly to a soulful hymn sung by a blind cleric.

Figure 1.1Entry gate of Miani Sahib Cemetery, Lahore: Illum-ud-Din Devotee of the Prophet

Figure 1.2 Tomb of Illum-ud-Din

Figure 1.3Entry gate to Mumtaz Qadri’s Tomb, Bara Kauh, Islamabad

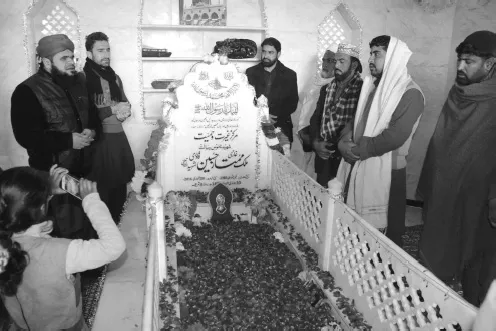

Figure 1.4 Mumtaz Qadri’s Tomb

These two figures provide us with a beginning and end of a tangled tale of how a set of statutes, the so-called blasphemy laws, became so sacred in Pakistan that criticizing them could make one a target for murder. The supporters of Qadri call him ‘the Illum-ud-Din of our time,’ but there are significant differences between the actions of the two assassins and in the reactions they elicited from the Muslim community. Illum-ud-Din killed Rajpal because of his publication of the book Rangila Rasul, which deliberately mocked the Prophet. Salman Taseer had proclaimed his love for the Prophet, but had criticized the vague wording and highly problematic implementation of Pakistan’s blasphemy laws. Illum-ud-Din had taken his action at a time when resurgent Hinduism, represented by the proselytizing movement Arya Samaj, was adding to the insecurity of the Muslim minority in colonial India. At the time of Qadri’s action in 2011, however, Islam was the official religion of the Pakistani state. Governor Taseer had come to the defense of Aasiya Bibi, an impoverished Christian woman who was sentenced to death for blasphemy on the basis of questionable evidence, and who posed no threat to the sanctity of the Prophet or the integrity of the Muslim nation. That is precisely the charge made against her, however, by the numerous books, articles, and newspaper op-eds that defended Qadri’s murder of the governor.

The purpose of this book is to understand how we got here. Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) 295-C is central to this story, although it is not its beginning. Passed in 1986 by the military government of General Zia-ul-Haq, PPC 295-C punishes with death or life imprisonment any person who “by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representation or by any imputation, innuendo, or insinuation, directly or indirectly, defiles the sacred name of the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him).”3 PPC 295-C has its origins in the Indian Penal Code (IPC) statutes passed by the British colonial government before independence, and particularly in IPC 295-A, passed in 1927, which imposes a three-year prison term or fine for anyone who “by words, either spoken or written, or by signs or by visible representations or otherwise, insults or attempts to insult the religion or the religious beliefs of that class.”4

But the statutes themselves are only a manifestation of the complex social and political dynamics that have made blasphemy laws such a Gordian knot for the Pakistani state that even after one of its own officials was assassinated, and even after dozens of its citizens were killed by mobs, the laws remain sacrosanct and impervious to reform efforts. This chapter outlines the beginnings of the path that led us to this point. I start by focusing on Chapter XV of the Indian Penal Code, Offenses Relating to Religion, which was enacted by the British colonial state. This will provide the foundation for our discussion of Pakistan’s blasphemy statutes, illustrating how ‘native religion’ was understood and managed by the colonial state, and how this history impacted the post-colonial state of Pakistan. I move next to the circumstances that led to the expansion of these statutes, and in particular to IPC 295-A in 1927. This statute can be directly tied to the publication in 1924 of Rangila Rasul, a book that was considered a ‘scurrilous attack’ on the Prophet Muhammad. The event was central in making a saint out of Illum-ud-Din, and it is illustrative of the competitive and turbulent public arena in which various Islamic groups competed vigorously for the right to define ‘true Islam.’ Finally, I discuss one of the results of Pakistan’s expansion of blasphemy statutes in the 1980s: Taseer’s murder and the widespread (although not universal) veneration of Qadri.

What is remarkable about the casting of Illum-ud-Din and Mumtaz Qadri as saints is that they come to this status ostensibly by protecting a set of laws that were first made by the British colonial government and were later expanded by the military regime of Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq. This is paradoxical, because the Sufi tradition in Islamic history calls for moving beyond human law to an understanding of the essence of God through the mediation of the saints and the comprehension of the ultimate truth and oneness of God. A prominent feature of Muslim history has been “the struggle to arrive at a coherent working relationship in society between the respective truth-claims of law and Sufism”5 (a struggle we will see below in the ongoing contestation between Barelvis, on the one hand, and Deobandis and Ahl-e-Hadith, on the other). Moreover, Pakistan’s blasphemy laws are not sharia laws, no matter what their proponents might claim.

What, then, can we make of Sufi-inflected groups claiming the status of sainthood for two young men who murdered ostensibly out of love for the Prophet? To say that blasphemy laws are Western and modern and have nothing to do with Islam is inadequate, because those who killed on behalf of these laws, and the millions more who approved of their actions, believed that they were serving the cause of Islam. To say that these two young men killed because Islam is an intolerant religion is inadequate, because it gives us no way of understanding how it is that Christianity, once known for its religious inquisitions, became tolerant, while Islam, historically known for its ability to accommodate differences, became so intolerant. Pakistan’s history saw the entanglement of two different traditions: sharia as it was practiced before the arrival of the British, and the English laws made for the colony. This brought together two sets of “deeply rooted, historically conditioned attitudes about the nature of law, about the role of law in society, about the proper organization and operation of legal system, and about the way that law is or should be made, applied, studied, perfected, and taught.”6 Contemporary blasphemy laws in Pakistan, as a result, are neither purely Islamic nor purely modern-secular.

The original legal framework for blasphemy laws, as set by the British, was grounded in the colonial understanding of how best to manage a religiously diverse population sensitive to apparent injury to their religious sentiments. After the Muslims of the subcontinent had a modern nation-state of their own, the colonial legal framework stayed mostly intact, but now Islamic concepts were brought into the legal arena and were used to justify expanding the blasphemy statutes. The bitter fruit produced by the selective incorporation of ‘Islamic’ laws into Chapter XV of Pakistan’s Penal Code has earned the country much notoriety – but it also provides a revealing look at the broader dynamic of the consequences for Muslim politics when a truncated and reframed sharia is functionalized to serve the interests of the state, or of political actors.

Colonial secularity and the ‘religious passions of the natives’

For the chroniclers of Illum-ud-Din’s life and death, the passage of IPC 295-A in 1927 was the singular service he rendered to the sanctity of the Muslim community in the subcontinent. This is a problematic assertion, however, since the statute was passed almost two years before Illum-ud-Din murdered Rajpal. I will take up that issue shortly, but let’s first briefly examine the origin of Chapter XV, Offenses Relating to Religion, in the 1860 Indian Penal Code drafted by Lord Macaulay. Section 295 of this Chapter prohibited the destruction, damage, or defilement of any place of worship or any object held to be sacred by any class of person; a note clarified that ‘objects’ did not include animate objects, and thus “killing a cow by a Muslim within sight of public road” could not be prosecuted.7 This proved to be highly problematic. In 1888, when a court declared that cows were not sacred objects, Cow Protection Societies sprang up in in most parts of India, and became one of the most highly charged symbols of Hindu nationalism.8 Section 296 prohibited the disturbance of any lawful performance of religious worship or ceremonies; section 297 prohibited trespass of any place of worship or cemeteries with the intent to wound the feelings of any person, or of insulting the religion of any person; and section 298 prohibited uttering any word or making any sound or gesture or placing an object in the sight of a person with the deliberate intent to wound his religious feelings.

I want to highlight two points from the discussion that surrounded the passage of these statutes. First is what I term ‘colonial secularity,’ by which the British colonial government adopted a policy of neutrality towards religion, not because they were importing secular English norms into the colony, but because neutrality was seen as the most pragmatic means of managing religious passions in India. Lord Macaulay argued that the inclusion of laws preventing injury to religious sentiments was crucial because “there is, perhaps, no country in which the Government has so much to apprehend as in India, from religious excitement among the people.”9 He goes on to say that “the religion may be false, but the pain which such insults give to the professors of that religion is real. It is often as real a pain and as acute a pain as is caused by almost any offense against the person, against property, or against character. Nor is there any compensating good whatsoever to be set off against the pain.”10 But there were also others, such as a certain Mr. Thomas, who worried that if “the Criminal Courts were to be at all times open to the zealots of different sections on every trifling occasion the result would be to foster bigotry, and to keep the religious animosities of sects at its height, as well as to interfere with individual security and peace.”11 Mr. Thomas was right to worry: the availability of legal remedies was eagerly seized upon by partisans of various kinds to argue their case for religious injury.

Second, the discussion around the statutes makes it clear that England itself was a Christian nation where there was no separation between church and state. Discussing blasphemy and English law, the document states that in England, blasphemous words “were not only an offense to God and religion, but a crime against the laws, state, and ...