- 350 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

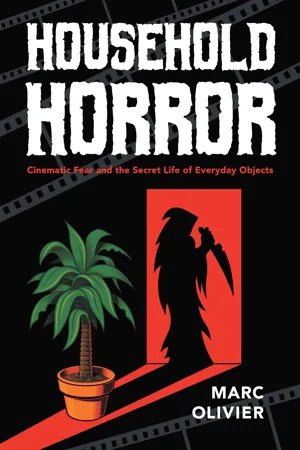

About this book

A scholar examines 14 everyday objects featured in horror films and how they manifest their power and speak to society's fears.

Take a tour of the house where a microwave killed a gremlin, a typewriter made Jack a dull boy, a sewing machine fashioned Carrie's prom dress, and houseplants might kill you while you sleep. In Household Horror, Marc Olivier highlights the wonder, fear, and terrifying dimension of objects in horror cinema. Inspired by object-oriented ontology and the nonhuman turn in philosophy, Olivier places objects in film on par with humans, arguing, for example, that a sleeper sofa is as much the star of Sisters as Margot Kidder, that The Exorcist is about a possessed bed, and that Rosemary's Baby is a conflict between herbal shakes and prenatal vitamins. Household Horror reinvigorates horror film criticism by investigating the unfathomable being of objects as seemingly benign as remotes, radiators, refrigerators, and dining tables. Olivier questions what Hitchcock's Psycho tells us about shower curtains. What can we learn from Freddie Krueger's greatest accomplice, the mattress? Room by room, Olivier considers the dark side of fourteen household objects to demonstrate how the objects in these films manifest their own power and connect with specific cultural fears and concerns.

"Provides a lively and highly original contribution to horror studies. As a work on cinema, it introduces the reader to films that may be less well-known to casual fans and scholars; more conspicuously, it returns to horror staples, gleefully reanimating works that one might otherwise assume had been critically "done to death" ( Psycho, The Exorcist, The Shining)." —Allan Cameron, University of Auckland

Take a tour of the house where a microwave killed a gremlin, a typewriter made Jack a dull boy, a sewing machine fashioned Carrie's prom dress, and houseplants might kill you while you sleep. In Household Horror, Marc Olivier highlights the wonder, fear, and terrifying dimension of objects in horror cinema. Inspired by object-oriented ontology and the nonhuman turn in philosophy, Olivier places objects in film on par with humans, arguing, for example, that a sleeper sofa is as much the star of Sisters as Margot Kidder, that The Exorcist is about a possessed bed, and that Rosemary's Baby is a conflict between herbal shakes and prenatal vitamins. Household Horror reinvigorates horror film criticism by investigating the unfathomable being of objects as seemingly benign as remotes, radiators, refrigerators, and dining tables. Olivier questions what Hitchcock's Psycho tells us about shower curtains. What can we learn from Freddie Krueger's greatest accomplice, the mattress? Room by room, Olivier considers the dark side of fourteen household objects to demonstrate how the objects in these films manifest their own power and connect with specific cultural fears and concerns.

"Provides a lively and highly original contribution to horror studies. As a work on cinema, it introduces the reader to films that may be less well-known to casual fans and scholars; more conspicuously, it returns to horror staples, gleefully reanimating works that one might otherwise assume had been critically "done to death" ( Psycho, The Exorcist, The Shining)." —Allan Cameron, University of Auckland

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Household Horror by Marc Olivier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

KITCHEN/DINING ROOM

1

REFRIGERATOR

THE KITCHEN IS A HUB OF DOMESTICATED MICROCLIMATES: the arctic cold of the freezer, the chill of the refrigerator subdivided into zones according to food type, the variable heat of the conventional oven, the misunderstood microwave radiation that bounces around a smaller oven, the circular hot zones of the stovetop, the storms of the dishwasher, and other no less dramatic shifts in temperature brought about by other appliances such as the coffee maker, the Crock-Pot, the pressure cooker, the ice cream maker, and the toaster. Heat and cold—or, more correctly, heat and various degrees of its absence—regulate essential functions of the domestic ecosphere. Each room of a house may be subject to heating and cooling systems not unlike those of ovens and refrigerators, but the kitchen harbors some of the most potent examples of matter impacted by energy transfer. The kitchen’s microclimates participate in sustaining, preserving, destroying, or otherwise altering organic life.

The Cold Womb

More often than not, the kitchen has been designated as a feminine space. Kitchen appliances, in turn, are often seen as extensions of the female body to which a range of temperatures and climatic conditions (ice cold, frigid, smoking hot, wet, dry, etc.) are disproportionately attributed. The colloquial expression for pregnancy “to have a bun in the oven,” though not complimentary insofar as it equates a pregnant woman with a household appliance, provides a telling example of a long-standing link between procreation, gestation, and kitchen technology. The phrase imagines the womb as an oven and, by the same logic, the oven as a womb, similar to “The Gingerbread Man” and other folktales of high-carb homunculi cooked up by women in the kitchen. Andrzej Zulawski’s Possession (1981), “a fairytale for grown-ups” according to the director, falls within that tradition, although instead of a bun in the oven, the story features a body in the refrigerator, and instead of piping-hot runaway baked goods, the woman of the house prepares a tentacular, glutinous golem through a miscarriage of groceries and bodily secretions expelled in the tunnels of the Berlin U-Bahn during an ecstatic trance.1 The aberrant offspring of a body in crisis disrupts a marriage, an affair, and two kitchens. When considered in relation to perishable food distribution, refrigerator-related household duties, and the desire of a woman to say “I” for herself, the miscarriage-birth emerges as an abject expression of identities both human and nonhuman, of a woman who runs hot and cold, and of refrigerators and their unspeakable contents.

“Possession is a fable whose moral I do not understand,” says Zulawski.2 And the director is not alone in his confusion. Possession was reportedly the most controversial film at the 1981 Cannes Film Festival.3 The French newspaper Le Monde wrote that it “traumatized” festival audiences.4 Invariably (and usually unfavorably), French critics linked the film to the Grand Guignol tradition of sensationalist theatrical horror, whereas Zulawski had imagined his work too serious to be mistaken for the disfavored genre.5 The French newspaper Libération called Possession “a cocktail of Polish obscurantism and Hitchcockian effects.”6 The New York Times characterized it as “an intellectual horror film,” adding, “That means it’s a movie that contains a certain amount of unseemly gore and makes no sense whatsoever.”7 Isabelle Adjani, rewarded at Cannes for her leading roles as both Anna (the woman who gives birth to, cares for, and copulates with the monster) and Helen (her kindhearted schoolteacher double), called the film “emotional pornography,” which, truth be told, is as good an explanation as any.8 Thoroughly rational attempts to unravel the plot are doomed because incomprehension is as essential to Zulawski’s project as it is to symbolist poetry or surrealism. During production, Zulawski often told people that Possession was a film about God—a concept that also escapes him. “I don’t know what God is,” says Zulawski. “I believe that if I did know, I wouldn’t make art.”9 Possession is not an atheistic attack on the notion of a divine being but rather a “quarrel against God” that Zulawski compares to a child crying to a father or an injured party facing a lawmaker.10

“Anyone can make a film, but making a film that has a soul is very difficult,” says Zulawski. “It is as if I were trying to make a golem.”11 And rumor had it, during preproduction, that Zulawski was in fact going to Berlin with Isabelle Adjani to make a film about a golem.12 Once the film was released, however, plot synopses forgot about the golem and attempted to couch the story along the lines of a bizarre bourgeois melodrama. Outlined as such, the plot follows Mark (Sam Neill) as he returns home from some sort of espionage mission in East Berlin to his wife, Anna (Isabelle Adjani), and son, Bob (Michael Hogben), in their West Berlin apartment, which faces the Berlin Wall. He soon learns that Anna has been having an affair with a man named Heinrich (Heinz Bennent). Fights ensue (so many that the Times called the film “a veritable carnival of nosebleeds”), the couple’s young son is neglected, Mark sleeps with Helen, and Anna cheats on both her husband and her lover with a cephalopodan six-foot phallic monster that she keeps in a love hideaway with a view of the Wall.13 The creature continues to transform as the body count rises. A head, hands, and feet soon stock the refrigerator shelves. The film spirals to its climax as the main characters ascend a staircase (meant to evoke Jacob’s ladder), and the drama ends in nothing less than the sounds of an impending apocalypse. The story is not your average tale of conjugal strife, but dialogue borrowed from Zulawski’s own failed marriage pierces through the narrative absurdity with the genuine agony of a relationship in crisis. Possession is indeed a domestic psychodrama, but it is also Zulawski’s film about the golem—not the clay golem of the director’s native Poland but something more intimate, something that must be understood in connection to banal domestic objects such as groceries and refrigerators.

Outlined to better represent nonhuman actors, Possession becomes a story of perishable groceries that participate in the creation of a golem. The creature not only materializes Anna’s emotions but also connects the cold chain network of food distribution to the home refrigerator as abject horror’s answer to the oven-womb. As absurd as it seems to consider how a kitchen appliance might react to a film (a thought experiment no less irrational than the film’s plot), one can imagine that if appliances could dream, then Zulawski’s golem, born from an oozing discharge of spilled milk, yogurt, eggs, and human bodily secretions—a half-baked, imminently perishable yet ever-thriving and metamorphosing entity—would surely haunt a refrigerator’s nightmares. Anthropomorphism aside, the refrigerator is an active prop in the film. Just as Anna and Helen are nearly identical human doubles with different souls, Anna’s two apartments have nearly identical refrigerators with radically different contents. The first holds eggs, milk, meat, and even clothing at one point. The second contains body parts and flowers from a lover. The first is often gripped by Mark, who admires and caresses its bright exterior when Helen sleeps over and cleans up. The second stuns and terrifies both Mark and Heinrich. Like all refrigerators, the appliances defy nature through climate control—an act of suspended animation or suspended decomposition depending on one’s point of view. Both of Possession’s refrigerators reside in apartments that face the Berlin Wall, which draws attention to how “cold” borderline conflicts can take on material forms.

In Possession, the refrigerator is a woman’s domain and serves as the primary signifier of domesticity, its failures, and its perversions. All of the characters seem to agree that a good woman keeps her refrigerator well stocked and clean. Helen, always clothed in white, is the picture of sanitary housekeeping. When Helen stops by to discuss concerns about Bob’s behavior at school, Mark puts her to work without a second thought. She gets Bob out of the bath, tucks him in bed, and then heads to the kitchen to clean up Anna’s mess. Mark enters the kitchen and runs his hand across the top of the refrigerator with a look of wonder. Twice he caresses the pristine cleanliness of the appliance while Helen washes the meat and blood from the electric knife that Anna had used earlier (in a domestic act that quickly spiraled into self-harm). Helen’s house, seen only at the end of the film, is modern, spacious, and impeccably clean. She feeds Bob a king’s breakfast on a gleaming white table. “Look at the kitchen,” says Zulawski to Daniel Bird in the DVD audio commentary. “It’s white. It’s clinical. We do try to make our surroundings clinically beautiful, clinically clear, or artistically clear, because we are lost. And this thread of being lost, lost, lost, lost, lost between the Berlins, the politics, the morals, it’s at the core of the film.”14 In an interview at the time of the film’s release, Zulawski explains that he associates the color white with Helen as a marker of “lucidity, goodness, heart” and the only real chance that Mark could have had to get out of his destructive relationship with Anna: “The more [Helen] was white, the more she colored the other story with intensity.”15 And yet when perfect Helen cleans up Anna’s mess in the kitchen and Bob asks Mark which woman he prefers, Mark replies, “Our mummy,” and Bob smiles. Like Zulawski, the father and son find clinical and artistic clarity less satisfying than colorful chaos.

Anna is almost never without bags of groceries. She is always stocking refrigerators but failing to do so properly. All of Anna’s domestic acts go awry even as her insistence on performing them intensifies. At one point, she gathers piles of clothes and shoves them into the refrigerator yelling, “I’m sorting out his things to take to the laundry!” Mark watches as she moves from stocking the fridge with clothes to emptying food from the cupboards. He tries to calm her. “But it’s my job!” she screams. “I’m better at it!” Anna’s many attempts at idealized domesticity are interrupted, malfunctioning, and short-lived. When Mark returns home from a confrontation with Anna’s lover, he finds Anna with Bob in the kitchen—a sentimental tableau of mother and child at a small table eating and singing “Baa-Baa Black Sheep.” But Mark’s arrival disrupts the scene, Bob exits the kitchen, and the fighting begins. While Mark yells, Anna continues to perform housework by madly putting things in the fridge. The argument ends violently, nosebleed oblige. Later, Anna returns and heads straight to the kitchen with bags of groceries. As Mark again yells at her, she unpacks meat, gets the electric knife and the meat grinder, and furiously cuts and grinds as if making hamburger were the most important thing in the world. Mark grips the refrigerator tightly while firing off accusatory questions. Anna turns the electric knife against herself—and Mark, after bandaging her neck, performs the same stunt on his arm. “It doesn’t hurt,” says Anna as she prepares to leave. A high-angle shot dwarfs Mark, who broods like a neglected child at Bob’s kitchen table. Outside, a private investigator trails Anna straight to the supermarket, where she buys two more bags of groceries for her other apartment. At Anna’s hideaway, foodstuffs become weapons. A broken wine bottle cuts the detective’s throat; yogurt in a bag becomes a makeshift mace to pummel a foe. Her refrigerator looks more like a morgue than a food-storage device.

Anna’s most intense perversion of refrigerator-linked duties occurs on a trip home from the supermarket. She carries a string bag filled mostly with milk, eggs, and yogurt—groceries that need refrigeration and that all clearly allude to fertility and procreation. She stops in a church and kneels before a statue of Christ on the cross, her string bag hanging at the level of her uterus. She lifts her eyes and moans almost like a woman in labor. This is the beginning of what she terms a miscarriage of “Sister Faith.” She exits the church and walks into the subway. Alone in the underground passage, she begins to convulse and scream in a fit as raw as anything in The Exorcist (1973). Her string bag, that external womb of eggs, yogurt, and milk, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: Kitchen/Dining Room

- Part II: Living Room

- Part III: Bedroom

- Part IV: Bathroom

- Conclusion . . .

- Filmography

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author