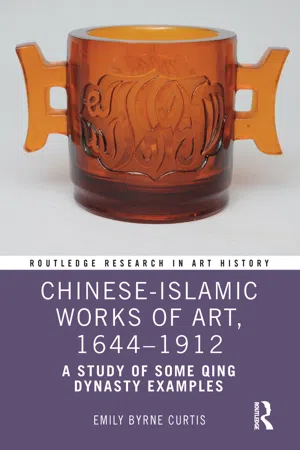

![]()

1 The arrival of Muslim artisans in China

Background

During the Later Jin period (後晉, 936–946), the first official dynastic history (zhengshi 正史) of the Tang dynasty 唐 (618–907) was compiled by a team of scholars headed by Liu Xu 劉昫 and Zhang Zhaoyuan 張昭遠. This chronicle was originally known as the Tangshu (唐書, Book of the Tang).1 However, in 1044, the Renzong emperor (仁宗, r. 1022–63) ordered that the work be revised. Elements of myth or superstition in the text were to be expunged and the style of prose altered to a less florid one, while new sections of a more practical nature were added.2 In order to differentiate between the two versions, the more recent edition was called the Xintangshu (新唐書, New History of the Tang) and the original history became the Jiutangshu (舊唐書, Old Book of the Tang). What is of particular interest is that both histories contain descriptions of Arabia (食窯, Da Shi) as well as of Persia (波斯, Bosi), and go on to give a short explanation of the Islamic religion. They also provide several references to the existence of Arab settlers in China during the Tang period.3

For instance, during the An Lushan rebellion (安史之亂, An Shi Zhiluan) in c.756–63, Caiph Al-Mansur sent over 4,000 Arab mercenaries to assist the Xuanzong emperor (唐玄, r. 712–56) in his efforts to suppress the uprising. Afterwards, some of these soldiers are believed to have settled in Northern China and married Chinese women. These histories also mention the existence of a well-established and extensive Arabic trade in Guangzhou (廣州, Canton), where the Muslims lived in a special quarter, was governed by Qur’anic law, with a kind of extra-territoriality imposed by Chinese authorities.4 Other Muslim autonomous communities could be found in cities such as Yangzhou (揚州) and Kaifeng (開封). As we have seen, although an Islamic minority existed in China, their social status was that of foreigners in one of two categories: they either provided military assistance or traded in luxury goods and medicines. No mention is made in any of the historical accounts of any Muslim artisans or craftsmen working in China. A pronounced change to this situation occurred towards the end of the thirteenth century, when the Mongols arrived in China under the leadership of Kublai Khan (忽必烈 , r. 1260–94).

Kublai was the first non-Chinese emperor to conquer all of China, and if one counts the Mongol Empire at that time as a whole, his realm reached from the Pacific to the Black Sea, from Siberia to modern-day Afghanistan – one fifth of the world’s inhabited land area.5

According to Chinese historical precedent, a new ruler’s official title made reference to an ancient region in China. However, in this instance, Kublai’s title would have referred to a place outside of the country and served as a constant reminder to the Chinese people that the new dynasty was an alien one. Kublai astutely avoided this dilemma by naming the dynasty Yuan, ‘the origin’ (元朝, 1271–1368), which not only alluded to its appearance in the I Ching (易經) or Book of Changes but also formed part of the phrase 大哉乾元 (da zai qian yuan), in which qian referred to Heaven and the Emperor.6

Textiles

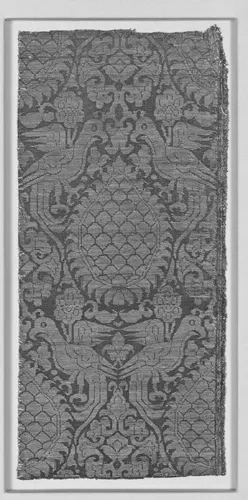

Kublai quickly assumed the role of patron of the arts, either from acute political awareness or for some other reason, and he generously supported all members of the artistic community.7 Artisans were especially valued, and he already possessed a sizeable body of craftsmen. The Mongols had a policy of carefully separating them out from the rest of their conquered populations.8 Regarding them as booty to be apportioned out, these skilled craftsmen were then transported, often over long distances, and set to work in new imperial workshops. Since textiles formed a central part of the Mongols’ political culture, it is not too surprising to learn that in Yuan China, ‘large numbers of West Asian and Chinese weavers’ could be found ‘working side by side’ turning out silk brocaded with gold thread. This was the fabled nasij cloth (panni tartarici; Fig. 1.1).9

Fig. 1.1 Textile fragment of woven silk and gold threads on a blue satin ground, the second half of thirteenth century to fourteenth century, l. 14 inches (35.6 cm), w. 6 ½ in. (16.5 cm.) Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Friends of Islamic Arts, 1996, no. 1996.286. *Public Domain*

Mongol rulers were quite taken with this fabric; Genghis Kahn is reported to have enthusiastically greeted merchants who came with ‘garments of gold brocade’, and even proclaimed them to be role models for his military officers. At this time, nasij was only produced in several locales in western Asia. However, by efficiently consolidating all the necessary resources such as gold, silk, and skilled craftsmen into one imperial manufactory, Kublai transformed it into an international commodity.10

The custom of using buttons to fasten one’s garments was another one of the innovations the Mongols apparently brought with them into China.11 A button may be defined as ‘a knob or flattened piece of some substance’, and it could be made out of a wide variety of materials.12 In China, this device is known as a toggle (墜子, zhuizi), which when passed through a loop certainly facilitated matters and provided an alternate method for closing one’s garments.13 The toggle also became a characteristic of traditional Chinese dress. Portraiture has been of little help in trying to trace toggles’ origin and development since, until recent times, it was limited to depictions of nobles, officials, and their wives in formal attire. Another possible reason for the paucity of Chinese pictorial or written records for the toggle is that they associated it with the ‘barbarians’ (the Mongols) from beyond the frontiers. The lack of reliably dated examples for this period is another issue, although one example in the Bieber collection may be confidently dated to 1901. This date is stamped on a British Trade dollar which was reused as a toggle. In this adaptation, Arabic script was added to the lappets of the cloud collar motif (see Chapter Four), on what originally had been the reverse side of the coin, with the figure of Britannia as Queen of the Seas depicted on the other side.14 While most of the toggles that dated to the late Qing period seem to have been worn by farmers, hunters, woodcutters, and the like, this is a topic which would benefit from further study.

Metalwork

The conquests of Genghis Kahn had resulted in the reopening of the roads between eastern and western borders. ‘A flood of Mohammedans of all kinds, Arabs, Persians, Bokhariots, converted Turks – and doubtless Uigurs – passed freely to and fro, and scattered themselves gradually over China in a way they had never done before’.15 This ‘flood’ included people traveling freely along the roads in Yunnan Province (雲南省), where, according to Marco Polo, one came upon ‘merchants and artisans’ in its principal city of Dali (大理市).16 As discussed above, the craftsmen who had been brought into China from other areas of the Mongolian empire had introduced new skills to the textile industry. An influx of skilled artisans in metalwork seems to have had the same effect in Yunnan.

Yunnan province is situated in a mountainous area which contains substantial mineral wealth. With deposits of ores such as copper, lead, zinc, tin, iron ore, and silver, these natural resources were used to make a wide variety of metal wares. Examples of bronze vessels are known, with some of them reinterpreting the forms and decorations found on Chinese archaic ritual vessels, while adding patterns and motifs that are entirely of their time.

The first piece to consider is an incense burner of cast bronze in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum (No. 198-1899). It is catalogued as being in the form of a shallow bowl with two monster-head handles (probably taotie masks, 饕餮, see Chapter Two), standing on three feet which were also ornamented with masks of ‘monsters’. The side is engraved with two panels of inscriptions on a punched ground and has two rows of bosses imitating rivets. Accompanying the burner is a wooden stand on three feet carved to imitate bamboo stems (Fig. 1.2).17

Fig. 1.2 Bronze Incense burner with relief Arabic inscription, Xuande mark on base (1426-35). Collection of the V&A Museum, no. 198-’99, h. 38.1 cm, w. 31.115 cm. Chinese Art, Stephen W. Bushell, vol. 1, 1906, fig. 43. *out of copyright*

Underneath the incense burner is a seal indicating that it was intended ‘For worship of the tutelary gods on the inner altar’ and the reign mark of the Xuande emperor (宣德, r. 1426–35), surrounded by two dragons in relief. The characters for the Arabic inscription are described as being in a ‘debased’ form, probably signifying ‘There is no God but God and Muhammad is his prophet’. As mentioned in Chapter Three and discussed further in Chapter Nine, the Arabic characters may have been rendered in Sini or Xiao’erjing script. Furthermore, the incense burner’s seal clearly indicates that it wa...