International Rivalry and Secret Diplomacy in East Asia, 1896-1950

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

International Rivalry and Secret Diplomacy in East Asia, 1896-1950

About this book

East Asia was a major focus of struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War of 1945 to 1991, with multiple "hot" and "cold" conflicts in China, Korea, and Vietnam. The struggle for predominance in East Asia, however, largely predated the Cold War, as this book shows, with many examples of the United States and Russia/the Soviet Union working to exercise and increase control in the region. The book focuses on secret treaties, 26 of them, signed from the mid-1890s through 1950, when secret agreements between China and the USSR, including several concerning the Chinese Eastern Railway, gave Russia greater control over Manchuria and Outer Mongolia. One of the most important was negotiated in 1945, when Stalin signed the Sino-Soviet Friendship Treaty with Chiang Kai-shek and the Chinese Nationalists, that included a secret protocol granting the Soviet Navy sea control over the Manchurian littorals. This secret protocol excluded the US Navy from landing Nationalist troops at the major Manchurian ports, thereby guaranteeing the Chinese Communist victory in Northeast China; from Manchuria, the Chinese Communists quickly spread south to take all of Mainland China. To a large degree, therefore, this formerly undiscussed secret diplomacy set the underlying conditions for the Cold War in East Asia.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

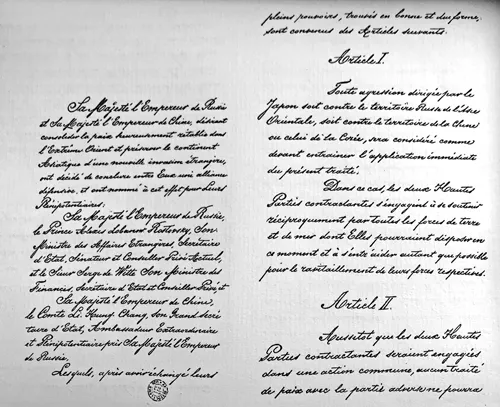

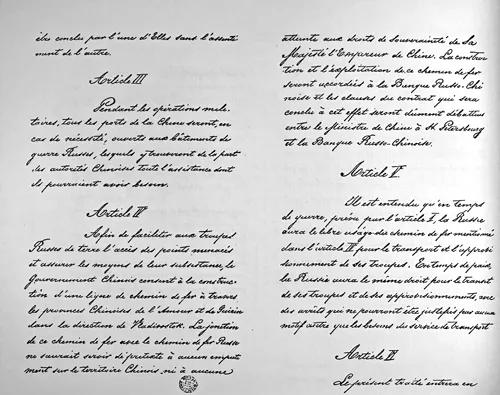

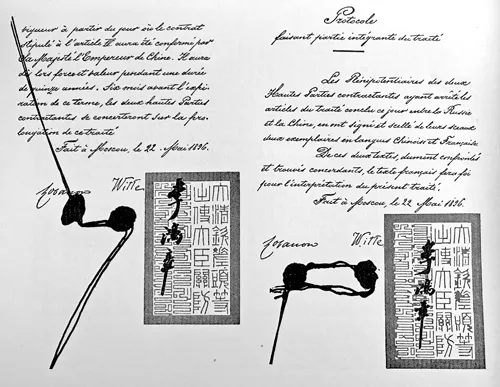

Treaty 1

3 June 1896—Sino-Russian Treaty of Alliance

Notes

Treaty 2

28 April 1899—Anglo-Russian agreement

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- Preface: territorial ownership as a guarded state secret

- Acknowledgments

- A word about sources

- Author

- Introduction: the international impact of secret diplomacy

- Treaty 1 3 June 1896—Sino-Russian Treaty of Alliance

- Treaty 2 28 April 1899—Anglo-Russian agreement

- Treaty 3 6 September 1899—Open Door Policy notes

- Treaty 4 5 September 1905—Portsmouth Peace Treaty

- Treaty 5 30 July 1907—Russo-Japanese secret protocol

- Treaty 6 4 July 1910—Russo-Japanese secret protocol

- Treaty 7 25 June 1912—Russo-Japanese secret protocol

- Treaty 8 7 June 1915—Sino-Russian-Mongolian tripartite treaty

- Treaty 9 3 July 1916—Russo-Japanese secret treaty of alliance

- Treaty 10 2 November 1917—Lansing-Ishii agreement

- Treaty 11 24 September 1918—Sino-Japanese Shandong agreement

- Treaty 12 30 April 1919—US-Japanese Shandong note

- Treaty 13 25 July 1919—Karakhan Manifesto

- Treaty 14 31 May 1924—Sino-Soviet secret protocol

- Treaty 15 20 September 1924—Soviet-Zhang Zuolin secret protocol

- Treaty 16 20 January 1925—Soviet-Japanese convention

- Treaty 17 20 January 1925—Bessarabia secret protocol

- Treaty 18 22 December 1929—Sino-Soviet Khabarovsk treaty

- Treaty 19 23 March 1935—CER protocol

- Treaty 20 21 August 1937—Sino-Soviet non-aggression treaty

- Treaty 21 23 August 1939—Molotov-Ribbentrop treaty impact on Asia

- Treaty 22 13 April 1941—Soviet-Japanese neutrality pact

- Treaty 23 11 February 1945—Yalta agreement

- Treaty 24 14 August 1945—Sino-Soviet friendship treaty

- Treaty 25 22 August 1945—General Order Number One

- Treaty 26 14 February 1950—Sino-Soviet friendship treaty

- Selected Bibliography

- Index