![]()

Part I

Managing complexities in research and in the field

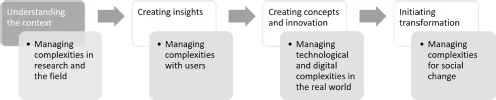

Step 1: understanding the context

Introduction

Part I of this book discusses how design is used in practical research when researchers encounter complexities emerging from the interplay of social interactions, historical and societal narratives, or ethical or emotional issues within the environments in which they work. Designers have cross-cutting, facilitative and supporting roles in development processes. This role positions them to manage complexities both when conducting their research and when carrying out practical work in the field. The chapters in Part I illustrate some research strategies and design methods for tackling such issues. Together, they present the first step of the design process for managing complexities.

Understanding the context is the first step of the design process presented in this book for managing complexities. In this step, designers generate understanding about the contexts in which they work. These contexts may be any practical work situation or research environment. The chapters in this section focus on designers entering the field. The aim of this step is to enable designers to understand the challenges and practicalities of everyday life, which will facilitate identifying new methods and discovering new possibilities for managing complexities through design. The first step is predominantly about creating trust and understanding around issues that are relevant and important to the communities with which the researcher is working. An important part of this process is carefully designing the role of facilitation and the methods for inclusion, participation and dialogue with communities.

![]()

1 Digital storytelling

Designing, developing and delivering with diverse communities

Hilary Davis, Jenny Waycott and Max Schleser

Digital storytelling in context

Since the mid-1990s, digital storytelling has been widely used as a participatory approach to enable people from various backgrounds to create and share short audio-visual narratives. For example, it has been promoted as an educational activity for developing skills in digital literacy and creativity (Schleser, 2012a), as a tool for supporting social work practice (Lenette, Cox, & Brough, 2015) and as an opportunity for intergenerational knowledge exchange in indigenous communities (Edmonds, 2014). Digital storytelling can take many forms and ultimately refers to any narrative created and shared using digital tools. However, the term ‘digital storytelling’ is often used to refer specifically to a participatory method that results in ‘a 2- to 5-minute audio-visual clip combining photographs, voice-over narration, and other audio (Lambert, 2009) originally applied for community development, artistic and therapeutic purposes’ (de Jager, Fogarty, Tewson, Lenette, & Boydell, 2017, p. 2548).

In community research and advocacy settings, digital storytelling has been particularly popular as a facilitated workshop activity to engage members of marginalised communities and encourage them to share their experiences (e.g. Schleser, 2014 a; Gubrium, Fiddian-Green, & Hill, 2016). Such projects often draw on the resources and processes developed by Joe Lambert and colleagues, who founded the Center for Digital Storytelling (Lambert, 2009, 2013; see de Jager et al., 2017, for a review). This process is participatory: storytellers are empowered to craft their own stories. Nevertheless, although the emphasis is on empowering storytellers, co-design is central to many of these projects: storytellers and researchers/facilitators work together to design visual narratives. This is meant to be a horizontal, non-hierarchical process, where the power imbalance between researchers or facilitators and participants is somewhat mitigated by the active role participants take in crafting their stories. However, this non-hierarchical participatory process can be difficult to achieve in practice (de Jager et al., 2017; Waycott, Davis, Warr, Edmonds, & Taylor, 2017). Researchers or facilitators may have a particular agendum or obligation to funding bodies, making it difficult to take a neutral stance when helping to craft participants’ stories. As co-designers, facilitators play a mediating role in the construction of meaning in the digital story (Waycott et al., 2017). Furthermore, multiple stakeholders may be involved, especially in digital storytelling projects that incorporate a community development or advocacy element; participation in the design of digital stories can, therefore, be complex and multi-layered. Ultimately, however, digital storytelling projects often aim to give voice to people who are otherwise disempowered (Waycott et al., 2017). This chapter will demonstrate that the co-design element of workshops is key to tackling issues of complexity when working with both individuals and groups of people from marginalised and diverse communities. We explore this further in the case studies that follow.

A key benefit of digital storytelling for this purpose is its inherent flexibility; that is, the use of a visual arts-based method allows participants to choose the story they wish to tell, define how they tell it and select data which they feel best represent their story. For instance, storytellers may include elements such as still photos, music, moving video and alternate methods of narration (e.g. voice-over, written text, note-cards). The flexibility of this methodology is that it allows storytellers to report on mundane, everyday experiences or highly emotional and subjective experiences (as illustrated by many of the examples ahead). Further, it allows people more comfortable with oral or visual storytelling practices to craft and tell their story using music, images or art, for example, rather than being limited to the written word. This resonates with particular cultures that emphasise oral traditions of storytelling (see Castleden, Daley, Sloan Morgan, & Sylvestre, 2013; Edmonds, 2014). The use of these additional elements may have a significant emotional impact on audience members. For example, audiences have reported emotional responses to digital stories that explored the everyday lives of people who are primarily housebound, with audience members commenting in particular on objects and places portrayed in visual form (Waycott & Davis, 2017). The ability to connect storyteller and audience is viewed as one of the strengths of digital storytelling (Gubrium, Krause, & Jernigan, 2014; LaMarre & Rice, 2016) and is perhaps one of the reasons it has been embraced as a means of sharing the stories of people from within diverse or marginalised communities. In the remainder of this chapter, drawing on digital storytelling projects in diverse and marginalised communities, we consider whether co-design might be redundant in today’s mobile and social media-rich world. Ultimately, we argue that co-design still has an important role to play in digital storytelling with diverse and marginalised communities.

Digital storytelling within diverse or marginalised communities

In this chapter, we use the term ‘diverse and marginalised communities’ broadly to refer to people whose voices are rarely heard in mainstream media. This can include people from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds, people from migrant or refugee communities, older or younger people and those experiencing physical or mental health conditions. This section of the chapter explores examples of digital storytelling used with marginalised or diverse groups. Our intention is not to create an all-encompassing list of digital storytelling projects that fall under these categories. Rather, we illustrate how digital storytelling techniques have been used to represent and support community representations of self.

The systematic review by de Jager and colleagues (2017) of digital storytelling in research included stories based on Lambert and colleagues’ digital storytelling process. The majority of research papers included in their study focused on marginalised community groups. They noted that some of the appeal of digital storytelling for use with marginalised groups is its ability to present the perspective or views of ‘counter narratives’ or ‘alternative interpretations of the world’ that challenge dominant views (p. 250). This is particularly the case for work that explores aspects of identity which are usually associated with stigma or social inequity. Examples of such stories include issues of gender, ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation (e.g. people who identify as LGBTIQ) or health stigma (e.g. people with HIV/AIDS or mental health issues; see, e.g., de Vecchi, Kenny, Dickson-Swift, & Kidd, 2017).

Other counter narratives refer to a sense of place or space in times of significant hardship, such as stories of women farmers ‘inside the farm gate’ impacted by drought, bushfires and other environmental and social factors in rural Australia (Farmer Health, n.d.). Some digital storytelling projects are concerned with either a sense of loss of place or transition between places and spaces, such as digital storytelling projects concerned with the experiences of people with refugee and immigrant status (Brushwood Rose & Granger, 2013; Lenette & Boddy, 2013). Historias de Migracao – Stories of Migration explores a Portuguese-speaking community in Stockwell, South London, England. The project, a collaboration between DigiTales and The University of Greenwich, England, explores urban exclusion for this community, reflecting on and sharing personal narratives (Digi-Taled, n.d.b). In addition, a range of projects connect with harder-to-reach populations, such as those experiencing homelessness (Woelfer & Hendry, 2010) low socio-economic status (Kent, 2015; Walsh, Rutherford, & Kuzmak, 2010) or rurality (Wake, 2012). Finally, there are digital stories concerned with personal or hidden spaces not usually seen by the outside community, such as reflections on life in institutional care or incarceration. Hidden Voices, for example, was a programme of expressive arts workshops in youth clubs and community centres in Sussex, England. The purpose was to raise awareness of the ‘hidden sentence’ faced by one of society’s most invisible groups – prisoners’ families (partners, carers, parents and particularly young people and children). A key aim was to highlight the impact of family imprisonment on well-being, relationships and life changes and to provide a platform for the promotion of the stories – and voices – of young people affected (Digi-Tales, n.d.a).

In our previous work, we have separately contributed to a number of projects that involved creating digital stories, or some form of digital media, with members of marginalised groups. Davis and Waycott, for example, created digital stories with three people who were housebound because of chronic illness. The stories provided an opportunity for the three storytellers to explore their life histories (before and after becoming housebound), to showcase meaningful objects in their homes and to share what it was like to be housebound. Participants’ stories were shared with community members through public displays of their digital stories at local events organised by their community health providers (Davis, Waycott, & Zhou, 2015; Waycott et al., 2017). This storytelling process was valuable for exploring the sense of connection or disconnection that the storytellers felt with their local community and exploring issues of loss – of mobility, family and work – while balancing this against memories of the past and hopes and dreams for the future (Waycott & Davis, 2015; Waycott et al., 2017). The stories provoked empathetic responses from members of the local community and from community health workers. Health workers noted that the visual format of these narratives created a powerful tool for advocating on behalf of their housebound clients (e.g. to demonstrate to the local government the importance of mobility issues when planning local infrastructure) and for educating the local community about chronic illness.

Schleser has conceptualised and conducted workshops which embrace smartphone filmmaking and use storytelling to work with organisations representing diverse community groups and in a range of social programmes as a form of creative engagement. These include the Local Mobile Filmmaking Workshops (Schleser, 2012a, p. 398) in East London communities with FutureVersity, Southwark Playhouse and B3 Media, initiated and facilitated through the FILMOBILE (see Schleser, 2010). This approach has recently been extended to encompass digital storytelling with people over the age of 60 in Melbourne, Australia, who created and showcased mobile digital stories focusing on their sense of place and space (McCosker et al., 2018; Digital Participation, n.d.). Figure 1.1, illustrates elements of the 60+ Online project, e.g., attending workshops, creating storyboards, and filming and editing digital stories using smartphones and tablets.

Figure 1.1 60+ online digital storytelling workshops.

Other initiatives have included projects with the community groups Spirit of Rangatahi (Schleser, 2014a), the Pasifika Youth Empowerment Program (Schleser, 2016), the NGO National Council for Woman (Schleser, 2012 b online, Rarotonga) and festivals such as Festival for the Future, East End Film Festival, Edge of the City (all in the UK), HeART beat (Russia) and Digital NatioNZ (New Zealand). The aim of these workshops was to create a bottom-up approach that enabled and empowered participants and that may potentially create sustainable social impact. In the projects with Spirit of Rangatahi and Pasifika Youth Empowerment Program, the aim was to create digital stories highlighting an insider perspective. The digital stories were shared in community forums and provided a means for the groups to showcase how they wanted to be represented. In both iterations, it was the first time that participants had worked with smartphones for storytelling. Both projects ran over multiple workshop sessions and included using a social media storytelling template created for this purpose (Schleser, 2015), engaging participants in filming and editing the digital stories and finally showcasing inspirational mobile and smartphone films. The editing sessions were conducted on the participants’ smartphones and in a collaborative editing process. A number of free apps (such as Adobe Clip and/or Adobe Spark Video) allowed participants to explore editing and learn the craft of storytelling.

These workshops incorporated a youth leadership framework. The community groups selected youth to be trained prior to the workshops. In the community workshops, these youth then trained their peers, with Schleser acting as a facilitator, narrative advisor and technician. Thus, the workshops provided a means to create an alternative representation of young people for the community in Wellington (New Zealand) and Rarotonga (in the Pacific). Edmonds (2014) followed a similar approach of engaging mentors from within the community to support digital storytelling with indigenous youth in Australia.

The key focus of the Pasifika Youth Empowerment Program was to tackle youth obesity by providing alternative lifestyle choices for Pacific youth. A team of researchers (Schleser & Ridvan, 2018) developed the Pasifika Youth Empowerment Programme (YEP), which consisted of five interactive learning modules in which 15 Pasifika youth (18–24 years) from Wellington, New Zealand, participated. The digital story approach developed by Schleser for this project was used to capture youth views and cultural perspectives and highlight their knowledge of environmental drivers of obesity. It demonstrated how young people can become important public health advocates within their communities. Similarly, Gubrium and colleagues conducted digital storytelling workshops with young women from a minority ethnic group with the aim of understanding and improving sexual health among members of that community (Gubrium et al., 2016).

The community project Spirit of Rangatahi demonstrates how young Pacific people can use smartphones as creative tools and learn how to use digital storytelling to create digital self-representations. The project developed a framework for youth leadership (through peer-to-peer learning) and sustainable digital literacy skills. The young filmmakers, aged 11 to 17, were invited to be part of the International Mobile Innovation Screening at Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision in Wellington, New Zealand, in 2014 (Schleser, 2018; see also ...