![]()

1 Introduction

‘Sorry, we’re closed’

On 13 May 2017, The Economist magazine published an article with the above caption, which referred to what the magazine called ‘the carnage in American retailing’. Shopping malls in the US have dramatically reduced in size, number, and patronage. The footprint of American malls has shrunk by 11.5 per cent, while sales have plummeted by more than 23 per cent since 2006. It is predicted that 800 department stores will be closing down soon. As more and more Americans shop online and overseas, jobs are being lost both in the retail sector and in auxiliary industries such as finance and commercial property development (The Economist, 2017a, pp. 54–56).

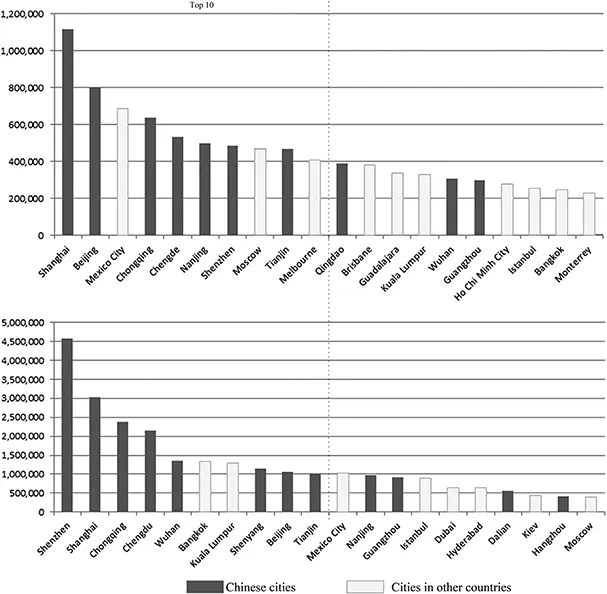

The situation in China is the exact opposite to what the Americans are experiencing. China is now the fastest growing shopping mall market in the world. In 2014, China, alone, contributed half of the world’s newly opened shopping malls (XinhuaNet, 2015). Shopping malls are springing up in many Chinese cities. According to CBRE (2017), a global commercial real estate service and consulting company, among the top 20 cities in the world for shopping mall completions in 2016, ten were in China, and seven of those ten Chinese cities were among the top ten (see Figure 1.1, top). What is more, when it comes to the overall floor area of shopping malls under construction, Chinese cities also dominated the world’s top ten by the end of 2016 (see Figure 1.1, bottom), which means the number of shopping malls in China continued to rise in recent years.

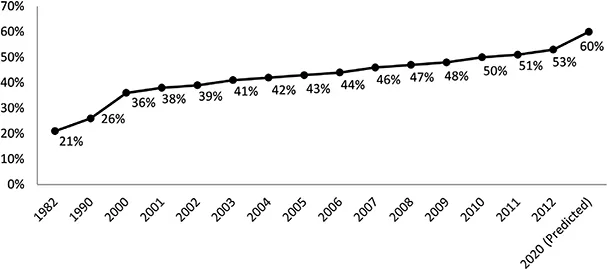

The expansion of shopping malls is part of what is called the ‘new urbanism’ in China (He and Lin, 2015). Four features of this socio-economic transformation require particular emphasis. First, the increasing level of urbanisation in China is unprecedented. In 1982, the share of urban population in China was only 21 per cent; now, according to the ‘National New-type Urbanisation Plan’ released by the State Council of China on 16 March 2014, more than 53 per cent of the Chinese population is urbanised (see Figure 1.2). The equivalent journey took the UK 100 years to make and the US 60 years to complete (The Economist, 2014), but China only took 33 years for this journey. In 1949, China only had 69 cities. By 2015, approximately 600 new cities had been built in the country (Shepard, 2015). The size of urban areas in China, as a result, doubled from 20,214.2 km2 to 45,565.8 km2 between 1996 and 2012. At the same time, the population density of urban area surged from 367 persons per km2 to 2,307 persons per km2 (NBSC, 1997, 2013).

Figure 1.1 Top 20 cities in the world for shopping mall completions in 2016 (top) and top 20 cities for shopping mall under construction by December 2016 (bottom) (square metres).

Source: adapted from CBRE (2017).

Second, the annual investment in real estate development in this process is dramatic. In 1996, real estate investment was only 843,983 million yuan; now it is over 22,364,545 million yuan, an increase of more than 25 times. From 2010 to 2014, the amount of investment in urban construction in Wuhan, a relatively small Chinese city (only 38.7 per cent the population of Shanghai), has been comparable with the UK’s entire expenditure on urban infrastructure in the same period (BBC News, 2014). However, the story of Wuhan is just the tip of the iceberg. In 2013 alone, the local government of Chongqing, another inland city and the youngest directly controlled municipality in China, spent 296.2 billion yuan on infrastructure and 301.3 billion yuan on real estate development. Both are dramatically higher than Wuhan, which spent 130.1 billion yuan on infrastructure and 190.6 billion yuan on real estate development that year. Meanwhile, in the same year, the total investment of Shanghai, which invested 104.3 billion yuan in infrastructure and 282.0 billion yuan in real estate development, is 20 per cent higher than Wuhan (China Business News, 2014). Because of these huge investments, China is building cities as well as real property development at a tremendous speed and on a mind-boggling scale. It is estimated that China has built a new skyscraper every five days in the past few years (BBC News, 2014). Between 2000 and 2014, 66 skyscrapers that are taller than 250 metres were completed in China, while in the US, the figure was only 12 in the same period (The Economist, 2014). Nevertheless, China seeks to further advance its urbanisation process. Urbanisation serves as a ‘gigantic engine’ for China’s economic growth, says Keqiang Li, the prime minister of China (Xie, 2012). So, as shown in the official urban development plan, China’s urbanisation level is being directed to reach 60 per cent by 2020 (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 China’s urbanisation level from 1982 to 2012, and predicted level in 2020.

Source: based on Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and the State Council of P.R. China (2014)

It is now accepted that the massive urban growth in China is heavily driven by neoliberalism (Harvey, 2007; Xu and Yang, 2010b), which is the third feature of the new urbanism in China. One core feature of Chinese neoliberalism is the marketisation of urban land. According to official data, between 2005 and 2012, about 19,746 km2 of land in China was sold to land developers.1 Meanwhile, speaking of the expenditure on urban construction, development and management, Hao Peng, the Director of the Urban and Rural Construction Commission of Wuhan, said only a small part of the investment is from the government (China Business News, 2014). His statement can be supported by the official data, which show that 54 per cent of infrastructure construction financing is from non-government sources (Chen, 2013) and, in 2013, up to 83.17 per cent of the fixed assets investment2 was from non-government sources.3 The next decade is very likely to witness a further increase of these ratios, because the central government has recently expressed its strongest support for the market, declaring the market force must play a ‘decisive role’ in China’s future growth at a plenum of the Central Committee in late 2013.

Fourth, in addition to the sheer size and level of urban population, investment, and marketisation, Chinese urbanisation is also taking place within distinctive political-economic and social-cultural contexts which are not only different but also qualitatively differentiated from what pertains in the West (Hassenpflug, 2010). David Harvey (2007, p. 120) describes this fourth feature as neoliberalism ‘with Chinese characteristics’. For example, in comparison with the West, Chinese urbanisation has more concentrated decision-making power, fewer landowners with whom to negotiate, and hotter speculative property markets in which there are great income disparities between existing and potential residents (Abramson, 2008). These conditions make it easier to consolidate land in China. As a result, urbanisation in China appears to be typified by megaprojects. The large-scale project-led urbanisation has created unprecedented building and population densities and absolute scale of urban changes in large Chinese cities which pose what Miao (2001, pp. 3–4) describes as special challenges to prevailing ‘Western’ notions of urbanity and the public realm by concentrating development decisions in the hands of an increasingly global and speculative class of investors and their designers (Abramson, 2008; Marshall, 2003; Olds, 2001).

In contrast, Western societies have had a longer experience of the market economy. Indeed, as Harvey (2014) points out, the private property rights that presuppose a social bond between that which is owned and a person who is the owner and who has the rights of disposition over which they own serve as the foundation of any market transaction. Western societies, as a result, have a long tradition of being apprehended and organised by distinguishing things that are public and things that are private (Benn and Gaus, 1983a; Edward, 1979). Meanwhile, the social bond between individual human rights and private property lies at the centre of almost all contractual theories of government in the West (Harvey, 2014). However, China is experiencing a transformation from a public ownership-based centrally planned economy to what Le-Yin Zhang (2006) calls a ‘market socialism’ economy in recent decades. Predictably, this process has resulted in Chinese society and cities developing relatively ambiguous property rights (Harvey, 2007, 2011a; Zhu, 2002; Lai and Lorne, 2014). It was only in 2007 that the first Property Law was implemented in China to clarify what rights people exactly have on their private property. But most of these efforts are focusing on macro-scale issues, including property structure, rural–urban land conversion, and land compensation. By contrast, at a micro-scale, everyday rights to get access and use the streets, plazas, and other urban spaces, namely ‘the publicness of the city’, remain unclear (Flock and Breitung, 2016; He and Qian, 2017; Wang and Chen, 2016).

Meanwhile, in non-Western traditions, the urban streets have much less political significance than in the West (Qian, 2014). For instance, before modern times, the public debates in China usually happened in some indoor spaces such as teahouses and guilds, rather than on the streets. Only in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, when the Treaty Ports were established at several Chinese cities after the Opium Wars between China and Britain, did political campaigns and debates begin to occur on the streets. Chinese urbanism has also been hugely influenced by the Western style of urbanism. Increasing openness to external engagement, the rise in the influences of Westerners and others in China, and China’s own aspiration as a global power all contribute to the social interactions between China and the rest of the world. These differences, understandably, can result in a special cultural understanding of the publicness of the city, and unique institutional and legal arrangements to deal with its relation with urbanisation in China.

These four features of the new urbanism in China have collectively led to the rise of new urban spaces in Chinese cities, especially shopping malls. However, only little research has been done about those new forms of urban space and, as a result, the dynamics and political economy of the production of these new urban spaces and the socio-economic implications brought about by them remain unclear. In 2015, a special issue in Urban Studies was devoted to the study of such spaces (He and Lin, 2015). The editorial of this special issue summarises China’s new urban spaces that have already been studied in the mainstream research, such as hi-tech and eco-industrial zones (Walcott, 2002; Zhang et al., 2010), new CBD and commercial space (Gaubatz, 2005; Marton and Wu, 2006; Yang and Xu, 2009), new residential space featuring Western-style single-family housing and gated communities (He, 2013; Pow, 2007; Wu and Webber, 2004; Xu and Yang, 2010b), cyberspace and new public space shaped by the internet and communication technologies (Puel and Fernandez, 2012; Yang, 2003), and new immigrant communities (Li, Ma and Xue, 2009; Lyons, Brown and Li, 2008). On this basis, this special issue seeks to update existing studies by adding studentified villages in the city (He, 2015), urban planning exhibition halls (Fan, 2015), and underground residence (Huang and Yi, 2015) to this list. However, the issue misses the most controversial of such spaces: pseudo-public spaces. Meanwhile, as part of the ‘Dialogues among Western and Chinese Scholars’ series, the journal of Modern China published a special issue (Vol. 37, No. 6) in 2011 focusing on the new urban development experiment in the Chinese city of Chongqing. This special issue, however, completely overlooks the rise of pseudo-public spaces and its consequences in Chongqing.

More recently, in 2017, Urban Studies published a virtual special issue to take stock of progress in Chinese urban studies to date. Apart from identifying four well-established research areas – namely (1) globalisation and the making of global cities; (2) land and housing development; (3) urban poverty and socio-spatial inequality; and (4) rural migrants and their urban experiences – He and Qian (2017, pp. 828–829), in the editorial of this special issue, also highlighted three emerging new research frontiers of urban China studies which are ‘not yet well represented in the journal or elsewhere, but of potentially great significance in the further comprehension and theorisation of Chinese urbanism’: (1) urban fragmentation, enclaves and public space; (2) consumption, middle class aestheticisation and urban culture; and (3) the right to the city and urban activism. As Nicholas Jewell’s (2016) recent book, Shopping Malls and Public Space in Modern China, makes clear, the rise of shopping malls is intimately connected with these three research themes. Jewell’s book, however, mainly tries to provide insight into the evolution and transformation of the shopping mall as an architectural typology through looking into China’s architectural modernity. The main aim of his book, as Jewell (2016, p. 4) himself makes clear, is to offer ‘a richer set of ideas about what a shopping mall may be.’ However, from a spatial political economy perspective, the following important questions have not been answered: why can shopping malls emerge and expand rapidly in the particular socio-political and economic context of China? How does the rise of shopping malls affect the publicness of Chinese cities? And what are the economic, environmental and socio-spatial consequences of this process for Chinese cities? To answer these questions, this book focuses on pseudo-public spaces in Chinese shopping malls.

Shopping malls and pseudo-public spaces

The shopping mall is a building typology that is deeply rooted in Western modernity. Its origin can be traced back to the nineteenth century. The period between 1820 and 1840 saw the construction of 15 retail arcades in Paris (Koolhaas, Chung, Inaba and Leong, 2001). Those arcades significantly changed the social life of Paris. Walter Benjamin (2002) recognises those arcades as the precursor of a fundamentally new kind of space, an indoor dream world of seductive commodities, or, in other words, a dream world of mass consumption. Spatially, thanks to technological progress in iron and glass that enable previously unimagined structures and roof spans, the arcade project ‘originates and is defined as a glass-covered passageway that connects two busy streets lined on both sides with shops’, as described in the Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping (Koolhaas et al., 2001, p. 230). The spatial structure of the arcade was fully manifested by the Crystal Place – an iron-glass structure built in London to house the Great Exhibition of 1851 – which provided an immense space in which to gather vast crowds under a single roof for the purpose of viewing goods. The iron-glass structure exemplified ‘the open display of commodities in a spectacular environment pre-empted the modern shopping experience’ and, in this way, generated a new architectural prototype (Koolhaas et al., 2001, p. 229).

After the 1851 London Great Exhibition, the spatial structure of the Parisian arcade and the barrel-vaulted ceiling, garden-like interior and sensory stimulation that emerged in the Crystal Palace became popular models to build retail spaces. However, it takes approximately 100 years for the shopping mall to take its definitive shape. By the 1940s, American cities faced oppressive congestion in the downtown area as well as the spectre of endless ribbon development on commercial highway strips (Hardwick, 2003). Against this backdrop, Victor Gruen, concerned about the damage caused by cars and looking for an antidote to suburban sprawl, published an influential book, Shopping Towns USA, in 1960. Gruen sees shopping malls as the means to provide America’s car-dependent suburban population with some of the benefits and amenities of urban life. He argues that the pedestrian mall should be built in suburbs with ample automobile parking around them. Importantly, in his book, Gruen (1960) proposes some far-reaching shopping mall design principles.

Gruen’s key design principle and the most significant innovation is the ‘dumb-bell’ structure of the shopping mall. This architectural form consists of a single internal shopping street (an arcade) with two large ‘anchor stores’ at either end of the route. The route is lined with a string of smaller shops. The ‘anchor stores’ are usually a branch of a national chain of department stores, whose appeal lies in the diversity of goods that they sell and in the assurance of quality possessed by their brand name. The ‘anchors’ act as ‘magnets’ to draw customers past the smaller shops. In this way, as Kim Dovey (1999, p. 126) reminds us, ‘new mall structure generated high pedestrian densities with high rental value. This added value lay in the potential to seduce the passing consumer into impulse consumption.’ Although it is hard to find an example that is built following the dumb-bell principle in its pure form, the manipulative control over the pathway from the car park to the anchor stores remains evident in most shopping malls built in the US in the second half of the twentieth century (Dovey, 1999). In this sense, Gruen’s book served as the benchmark for the evolution of the shopping mall, assuming an almost biblical significance f...