Cross-Bordering Dynamics in Education and Lifelong Learning

A Perspective from Non-Formal Education

- 172 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Cross-Bordering Dynamics in Education and Lifelong Learning

A Perspective from Non-Formal Education

About this book

Education as a concept has long been taken for granted. Most people immediately think of schools and colleges, of classes and exams. This volume aims to highlight non-formal education (NFE) in its various forms across different historical and cultural contexts. Contributors draw upon their experience as educators and researchers in comparative education and sociology to elucidate, compare, and critique NFE in Asia, Europe, Latin America, and the USA.

By mapping out NFE's forms, functions, and dynamics, this volume gives us the opportunity to reflect on the myriad iterations of education to challenge preconceived limitations in the field of education research. Only by expanding the focus beyond that of traditional schooling arrangements can we work towards a more sustainable future and improved lifelong learning.

This book will appeal to researchers interested in non-formal education and comparative education.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part I

Dynamics of non-formal education

1

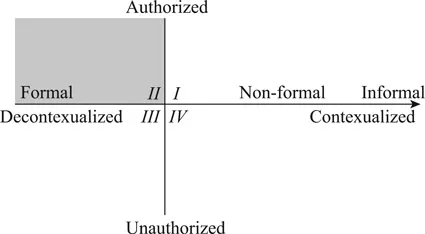

Boundaries and dimensions of NFE with strong formal school system in Japan

Introduction

1 The Japanese education system for the youth

1.1 NFE in formal schooling

1.2 Alternative schools

2 Adult education

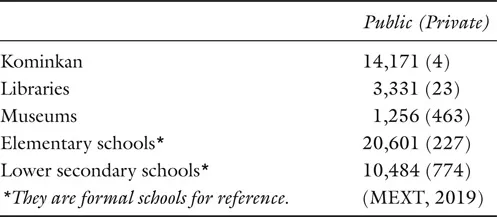

2.1 Social education system

2.2 Evening classes

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Series editor’s note

- Introduction: dynamics and analysis from non-formal education

- PART I Dynamics of non-formal education

- PART II Width and depth of non-formal education

- Index