On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, were murdered in Sarajevo. At the time, few would have predicted that a month later, Austria-Hungary would declare war on Serbia, the nation it believed was behind the assassination of the heir to the Habsburg crown. The Habsburg government hoped that this would be the beginning of a third Balkan war, but officials were cognizant of the fact that it could escalate into a wider European conflagration. That was exactly what happened.

The question of the origins of the Great War is really two questions: (1) Why did Austria-Hungary decide to go to war against Serbia? (2) Why did this decision lead to a world war instead of a third year of fighting in the Balkan peninsula? Both are important questions with complex answers. The chapter on Austria-Hungary addresses the first question, and the rest of this book offers an answer to the second question. This work will not reveal previously undiscovered archival material. Rather, it is an attempt to evaluate recent work on these questions that has been done and do it without the preconceptions that have created some blind spots in how we think about the origins of the war.

In the United States, the World War One Historical Association began their commemoration of the centennial of the war in November of 2013 with a symposium, “The Coming of the Great War,” at the National World War One Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. The symposium serves as a good reference point to discuss the state of scholarship on the origins of the First World War.1 The symposium began with Holger Herwig providing what can fairly be considered the standard assessment of responsibility: “Historians by and large agree that Imperial Germany bore a major responsibility for starting World War I. By fully backing Austria-Hungary’s play against Serbia after the assassinations at Sarajevo of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie on 28 June 1914, Berlin assured that what might have been a third Balkan war instead expanded into a general European war.”2 The judgment is not limited to historians. Political scientist Frank C. Zagare frames the issue in this way: “A second important question is whether the crisis in Europe was inevitable, whether Austria-Hungary and Germany could have been deterred from instigating a crisis in Europe.”3

Enmities between lesser powers can have unexpected and far-reaching consequences when outside powers choose sides to promote their own interests. In the years before World War I, Russia chose to become Serbia’s protector, both in the name of Pan-Slavism and also to extend its influence down to Istanbul and the straits leading out of the Black Sea. When Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, Germany, feeling it had to support Austria-Hungary, declared war on Russia, even at the risk of a world war. Because of alliances and friendships developed over the previous decades, France and then Britain were also drawn in to fight alongside Russia. Thus the war turned almost at once into a wider one.4

All the works squarely place the blame on Germany for transforming what could have been a local conflict into a European conflagration. These propositions reinforce the Treaty of Versailles and Article 231, commonly referred to as the War Guilt Clause, which blames Germany for the war and its damages, thus laying the legal and moral groundwork for reparations. Both Herwig and MacMillan support the idea of German aggression and responsibility for the escalation of a third Balkan war into the First World War. However, MacMillan’s comment is particularly problematic. She writes, “When Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, Germany, feeling it had to support Austria-Hungary, declared war on Russia, even at the risk of a world war.” What she omitted from this statement is the fact that Russia had begun the process of mobilization against both Germany and Austria-Hungary before the latter declared war on Serbia and more than five full days before Germany declared war on Russia. Moreover, the contention that France was drawn into the war frames the issue in such a way as to make France appear as a secondary, if not passive, participant in the events leading up to the war. This is a standard view in the Anglophone world; but it is also a view that needs to be reassessed and revised.

In February of 2014, the BBC News Magazine online offered “World War One: 10 interpretations of who Started WWI.”5 Of the ten people asked—Max Hastings, Richard J. Evans, Heather Jones, John C.G. Röhl, Gerhard Hirschfeld, Annika Mombauer, Sean McMeekin, Gary Sheffield, Catriona Pennell, and David Stevenson—only Richard Evans does not blame Germany in some fashion. He places the greatest responsibility on Serbia. The other nine include Germany, seven include Austria-Hungary, three include Russia, and two blame all six nations (Austria-Hungary, Germany, Britain, France, Russia, and Serbia).

The debate over responsibility (or guilt) started before the Versailles Treaty was even signed. In his useful summary of the historiography of the topic up to 1990, John Langdon reports that the French delegation had suggested Article 231 (the “war-guilt clause”) to stress Germany’s responsibility for the war and to justify reparations.6 It was no coincidence that Articles 232–234 addressed the question of reparations and Germany’s culpability. The cry of German chancellor Philipp Scheidemann—“The hand will wither that signs such a treaty”—was indicative of Germany’s understated reaction to the treaty as a whole and Article 231 in particular.7

Langdon’s work provides a standard interpretation of the historiographical path of responsibility for the outbreak of the war. Immediately after the war governments provided edited (and selected) papers to justify their actions leading up to the war. For the Entente powers, especially France, this was used to justify the French position that they had fought a defensive war. The French historian Pierre Renouvin embodied the link between history and politics. He served on the editorial staff that compiled and released the Documents diplomtiques français (1871–1914). In 1925, he published Les origins immédiates de la guerre, which remained silent on the importance of Poincaré’s visit to St. Petersburg and reasserted that the lion’s share of the blame falls on the Central Powers.8 At almost the same time, a counter position, arguing for collective responsibility, emerged. This position has unusually been referred to as “revisionist.”9 Understandably, World War II played a role in reducing interest in World War I. But that would change in the 1960s, with the publication of Fritz Fischer’s two works, Griff nach der Weltmacht and Krieg der Illusionen.10 Fischer places the blame squarely on Germany’s shoulders and draws a direct line from Wilhelmine Germany to the Third Reich. There are few today who would still embrace all of Fischer’s conclusions, but his work and the work of his students and his students’ students continue to receive a sympathetic hearing in the Anglophone world.11

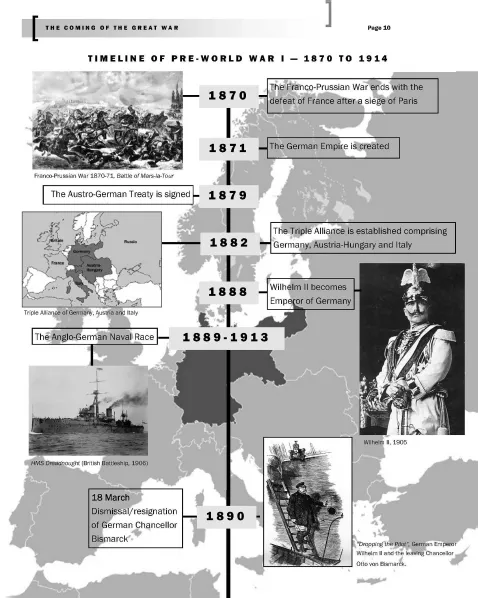

Winston Churchill was probably not the first person to say that history is written by the victors, but that certainly appears to be the case when it comes to writing about the Great War. The previously cited examples reflect the need to frame the war around the theme of German aggression. To give one more example, the symposium magazine referred to earlier included a time line for events leading up to the war (see Figure 1.1). Where does the magazine see fit to start the time line? It begins with the 1870–1871 Franco-Prussian War. By starting the time line with the Franco-Prussian War, the problem of the First World War is framed in terms of German aggression and expansion. A strong new nation appeared on the European scene, and it had upset the balance of power. It was only a matter of time before Germany was at war again. This starting point reflects a Western bias and keeps the focus on Germany as the cause for rocking Europe’s boat. Even the image used in the background of a dark Germany, distinct from the rest of Europe, suggests that Germany is the problem. Strangely, the Russo-Turkish War of 1878 is nowhere to be found on this time line. This omission is important because it had a direct impact on the destabilization of the Balkans. One provision of the treaty ending the conflict (Treaty of Berlin) established the rights of Austria-Hungary to administrative authority over Bosnia and Herzegovina with the understanding that at a later date the Habsburg Monarchy could incorporate the provinces directly into their empire. If war is at least in part the result of the breakdown of international consensus, the vast majority of 19th-century historians would point to the Crimean War as the event which first challenged the concert system that had prevailed since the end of the Napoleonic Wars. But like the Russo-Turkish War, it is not to be found on this time line. One reason is that it would not implicate Germany (or Prussia); the other reason is a reflection of the Western European bias. Western Europe is the center; thus Eastern Europe and the Near East are at the periphery.12

Figure 1.1 First page of the time line in World War I 2013 Symposium: The Coming of the Great War (Kansas City, MO: World War One Historical Association, 2013), 10.

The Western bias in the coverage of the war has the unintended consequence of diminishing the importance of actions in Eastern Europe (and beyond) in how the Anglophone world thinks about and presents the Great War. The British Council recently released a report entitled “Remember the world as well as the war. Why the global reach and the enduring legacy of the First World War still matter today.”13 Its executive summary notes, “The UK’s public knowledge of the First World War is quite limited.”14 The report’s framing of the war and its findings reveal the blinders that the Anglophone world tends to have on its perspective on the war. For example, this is how the report describes Russia’s entry into the war: “Russia’s decision to embark on military operations in mid-August 1914 opened up the Eastern Front and bought its Western allies welcome breathing space in Belgium and France.”15 The misrepresentation packed into this statement is stunning as well as revealing. A reasonable interpretation of this statement is that Russia entered the war late to help its Entente partners, again putting the focus on the Western Front. It would also be incorrect. Great Britain was not hoping that Russia would enter the war and open an Eastern Front. It was already open before Britain declared war. Russia was the first to mobilize for war in late July, not mid-August, and hoped that Great Britain would come to its aid and take some of the pressure off of Russia on the Eastern Front—it was confident of French support, as will be discussed later. To have a statement so misleading and so focused on the West in a document that was designed to emphasize the global scope and impact of the war is difficult to fathom.

The report reveals another example of the tunnel vision that unfortunately appears so embedded in the British understanding of the war. In what the report calls a “case study,” an anecdote is told about a Hammamet Conference held in Tunisia in 2012 to discuss the “Arab Spring.”

The opening speaker of the conference, a senior adviser to the Tunisian prime minister, talked of the need to build trust and understanding between his region and the UK. But he did not start with the here and now. Instead, he went back 100 years, when millions of people became embroiled in a global conflict that would come to be known as the First World War. He focused on two events in particular. Firstly, the 1916 Sykes—Picot Agreement, which proposed the division of much of the Middle East into British and French spheres of influence. Secondly, the 1917 Balfour Declaration: a letter by the British Foreign Secretary which paved the way for the creation of the state of Israel and the associated ongoing conflict with the Palestinians.

So, to their surprise, many of the UK delegates in Tunisia last year found that these two documents—almost forgotten in the UK—hold strong currency in a region they were visiting with the intention of forming relationships. As in this example, these historical events can in some circumstances fuel the opposite: resentment and distrust.16

The report mentions at several points that many in the UK may be surprised to find that some have negative views towards the UK because of the war. Perhaps it is the conceit of the victor that allows for such a perspective. It is not a conceit that should influence historians, but it does appear to do so.

In The Projection of Britain, Philip Taylor writes, “Until the final decades of the nineteenth century, Britain’s supremacy in the world was considered to be so self-evident that there was felt to be little call for a programme of propaganda overseas.”17 This self-assuredness was perhaps just an international projection of the Victorian morality that associated financial success with moral correctness. The position rested on two assumptions that could not be questioned: the centrality of Britain in t...