- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Social Movements, Nonviolent Resistance, and the State

About this book

This volume probes the intersections between the fields of social movements and nonviolent resistance. Bringing together a range of studies focusing on protest movements around the world, it explores the overlaps and divergences between the two research concentrations, considering the dimensions of nonviolent strategies in repressive states, the means of studying them, and conditions of success of nonviolent resistance in differing state systems. In setting a new research agenda, it will appeal to scholars in sociology and political science who study social movements and nonviolent protest.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Social Movements, Nonviolent Resistance, and the State by Hank Johnston in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

Analyzing social movements, nonviolent resistance, and the state

Among sociologists and political scientists, the field of social movement and protest research has grown in a relatively short span of time to become a central and vibrant social science subdiscipline. This rise was spurred by the increase of mostly nonviolent protest in North America and Europe as a way of doing politics, that is, contentious politics – noninstitutional collective action that arises when politicians are unresponsive to citizen demands. Since the huge student, antiwar, and civil rights mobilizations of the 1960s and 1970s, the social movement sector has expanded greatly (Meyer and Tarrow 1998; Dalton 2002; Dodson 2011; Rucht 1999; Soule and Earl 2005). Today, the nonresponsiveness of politicians and policymakers fuels movements as diverse as Black lives movement, #MeToo, and Trumpism in the US.

Similarly, beginning with small steps about the same time, most notably with the seminal scholarship of Gene Sharp (1973) and Johan Galtung (1969), there has been a slow but steady growth of academic interest in nonviolent strategies and peaceful tactics of challenge and resistance to the state – typically repressive states that limit citizen freedoms.1 Again, much of the interest in this area is among sociologists and political scientists and includes many scholars – like myself and most of the contributors to this volume – who bridge the field of nonviolence and social movements via research interests in resistance against repression. Studies of nonviolence have increased in recent decades as autocratic regimes have toppled worldwide, and research shows the utility of nonviolent tactics in successfully achieving regime change (Ackerman and DuVall 2000; Chenoweth and Stephan 2011; Karatnycky and Ackerman 2005; Martin 2007; Nepstad 2015a; Schock 2005, 2015). This volume brings together essays of several scholars whose important work has advanced both the nonviolence field and its intersection with social movement research.2

It is not coincidental that these two research foci have flourished in tandem. As Kurt Schock indicates in chapter three, they developed during a historical epoch when strategies of regime change transitioned from violent anticolonial and Marxist-Leninist-Maoist insurgencies to movements of resistance that were mostly nonviolent. Especially important were the movements that brought about the transformation of high-capacity Leninist socialist states, as well as several successful challenges to lower-capacity autocratic states in Asia and South America (Boudreau 2004; Schock 2005). These sea changes in regime and governance have provided the social sciences with the raw data to gauge the effectiveness of nonviolent resistance. Much of these data are quantitative indicators in the international studies tradition, plus an emerging body of protest data (as the dependent variables) based on developments in database construction and machine reading of media reports, a methodological trend in the social movements field during this same period.3 Domestically, in North American and Western European countries, democratic institutions and political norms have adjusted to broad social changes in class and economic structures to produce what have come to be called “social movement societies” (Meyer and Tarrow 1998), or the “movementization of society” (Melucci 1989), where protest is recognized and accepted as another means of doing politics – and, importantly, most of these activities are nonviolent as a matter of course. Whether they are intentionally so, as in the principled nonviolence à la Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., is a question we will examine in this volume as we probe different state contexts. Its second section offers several important and provocative considerations of regime contexts, how these affect mobilization, and the data used to analyze challenges.

This introductory chapter probes the intersections between these two research foci and their empirical groundings in democracies and nondemocracies, and especially this last category where so much of the nonviolence literature has focused. It is worth pointing out that repressive contexts are less studied in the literature of the social movements field. Indeed, an informed estimate would locate 80% of the field’s research in Western liberal democracies and not repressive states – for obvious reasons of frequency of occurrence. Methodological risks also restrict the kinds of data available for repressive states, which tends to limit eyewitness reports from events in the streets and plazas. There are, of course, exceptions (cf., Bayat 2013; Fu 2018; Lee and Zhang 2013; Johnston 2005; O’Brien and Li 2006; Perry 2002; Stern and Hassid 2012; Straughn 2005 – plus Moss and Clarke in this volume), and by taking the two research strategies in tandem, large databases and street-level observation, we can advance the field in significant ways, as the collection of reports in this volume demonstrates. Moss’s chapter six, Clarke’s chapter eleven, plus my own empirical observations in this introductory essay, all take grassroots foci to engage the state side of the equation. Case’s chapter deconstructs nonviolent protest events in repressive regimes with fine-grained observations about tactics, as does Isaac’s in the twentieth-century US South.

More generally, the pages that follow will probe what the study of nonviolence can gain from the theoretical and methodological insights of the social movement field. Its narrative rests, above all, on the recognition that nonviolent movements are social movements, and that peaceful resistance is a form of contentious politics. The tools of analyzing the latter can and should be useful in understanding and situating the dynamics of the former. The themes of this chapter and those that follow all highlight that there is a strong syncretism between the two foci, and that that the analysis of one enriches the analysis of the other in ways that, we hope, will change conversations and research agendas for years to come. Let us begin by stepping back and making a few general observations about the overlaps between the two fields.

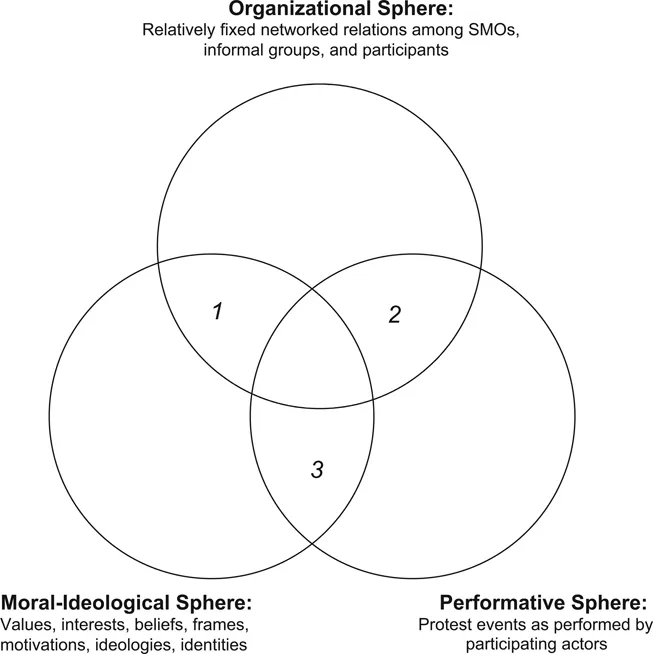

Dimensions of social movement analysis

Charles Tilly was a prescient analyst of the history of protest and politics and a leading theorist of contentious politics. He had little to say about nonviolence as a strategy, but a lot to say about the highly relevant concept of protest repertoires, their historical evolution, and their relation to the state – and, of course, nonviolent tactics are one element of the modern protest repertoire. In years of the field’s early growth, he recognized that how analysts approach a protest movement not only shapes what they see but also directs attention to overlaps in conceptual and methodological perspectives. In his theoretical treatise on protest and the state, From Mobilization to Revolution (1978 : 8–9), Tilly suggests that there are three fundamental dimensions to the study of social movements: (1) the protest actions that make up a movement’s repertoire; (2) the ideas – including moral precepts – that define injustices, guide protests, unify members, and ultimately form the basis of collective identity; and (3) the groups and organizations that make up the movement by mobilizing and participating in the events. Forty years after Tilly penned these observations, we can broaden the scope of these three analytical dimensions to better reflect new findings and how the field has advanced, for example recognizing advances in network analysis in the organizational sphere, movement frames and collective identity in the moral-ideological sphere, and emotions and strategic adaptation in the performative sphere. There is a movement-centric quality to this three-part analysis, which we will expand in the next section by considering other actors in the field of contention, but for now, let us consider Figure 1.1 (next page), which updates Tilly’s original analysis.

Groups, organizations, networks

As depicted by the top circle in the figure, a focus on mobilizing organizations must now include the fundamental network structure of a social movement (Diani 1992; Diani and McAdam 2003; della porta and Diani 2006), not just the focus on social movement organizations and their resources characteristic of the 1970s and 1980s. In other words, a focus on social movement structure means recognizing that there are numerous groups and organizations in the movement’s orbit, networked by interpersonal and organizational linkages but also divergent in their overall assessment of what is to be done and how – an observation that invokes the other two dimensions. This means that, when we speak of nonviolent movements, some constituent groups may be firmly shaped by the discipline of nonviolent practice, but others may be less committed. There are empirical cases, as discussed by Benjamin Case in chapter ten, when protest movements characterized as “basically nonviolent” from a 30,000-foot perspective often have outbreaks of property destruction, fights, and violent confrontations with police. Moreover, there are outlier and renegade groups on the radical flank, whose consequences for the movement have been chronicled by Haines (1988). These variations are reflected by the overlapping segment two in the upper-right of Figure 1.1, which represents the intersections among the different organizations and how actions are actually performed in the street. The analyst interested in explaining these variations is invariably directed toward the center of the figure where dimensions of the ideas and meanings that unite groups and bind network configurations are brought into the analysis. Of this central intersection of ideas, organization, and performance, the chapters in this volume will have much to say.

Figure 1.1 Analytical dimensions of social movements

Source: Adapted from Tilly 1978: 9.

The moral-ideological sphere

This is a dimension of social movement analysis that was underrepresented by resource mobilization and political process theories of the 1980s and 1990s, but resurrected in part by the popularity of the framing perspective (Snow and Benford 1988, 1992; Snow et al. 2014, 1986). Distinct from the theoretical concepts of the organizational dimension – social movement organizations (SMOs), their resources, structure, networked relations, ties to the state, notably elite accessibility – here we have factors such as moral and ideological commitment, collective identity, prognostic and motivational frames, and interpretative processes, that is, ways of looking at movements as mental constructs that precede action and guide it. This dimension of movement analysis was prevalent during the collective behavior phase of the field’s development 50 years ago, when concepts such as grievances, relative deprivation, and social-psychological processes of meaning articulation drove the field’s research. As Turner argued (1996), the rise of the resource mobilization perspective tended to obscure the moral dimension – throwing the baby out with the bathwater, so to speak – but recent dynamic and processed-oriented approaches better recognize that two dimensions are in recursive relationship, the relative importance of which is determined by the empirical case under consideration.

In the study of nonviolent movements, the realm of ideational constructs is absolutely central because herein reside the guiding principles of the struggle, whose normative guidance and moral authority vis-à-vis the state are key elements of how contention unfolds (Abu-Nimmer 2003; Barash and Webel 2009; King 1999; Magid 2005; Nepstad 2015a). Also, the role of religious beliefs in nonviolent movements resides here. Policy-oriented movement campaigns guided by faith or organized by faith-based groups are certainly not uncommon but are underrepresented when looking at the empirical distribution of contentious politics in the democratic West (but see Austin 2012; Nepstad 2004; Hondagu-Sotelo 2008; Wood 2002) and the distribution of research in the field of social movement and protest studies.

Protest performances

Tilly described the third dimension as the protest event, the performance of marches, demonstrations, and site occupations that are the defining activities of social movements and their fundamental means of attracting the attention of political elites. In my updated version of Tilly’s diagram, I lay stress on the performance aspect of this event-action dimension to reflect developments in cultural sociology. The concept of social performance is central to the contemporary analysis of culture in the social sciences, whereby the action is analyzed in association with its interpretations among those who witness it and/or are engaged with it. This is a recursive process of creating culture, that is, the production of meaning through the interaction of the actors and the audience (Alexander and Mast 2006; Eyerman 2006; Alexander 2011; Johnston 2011a, 2016; Norton 2004). In a cultural-analytical sense, therefore, protests should not be analyzed solely in terms of movement events, but also by how they are interpreted by various audiences and onlookers, and their (performative) reactions to it.

The movement-centric character of the figure means that the full cast of players in protest performances, the onlookers, the counterprotesters, the police, the military, and other agencies of social control (especially relevant in repressive regimes) are underrepresented, and that the dynamic unfolding of movement performances is not adequately accounted for without bringing in “the other side” of the equation. In social movement analysis, the starting point of protest performances is the normative understandings of appropriate action that are part of the modern repertoire (Tilly 1978, 1995, 2006, 2008). In democracies, this includes normative understandings of the “other side” as well, most notably, the agents of social control who usually respect the right to protest – within limits, but, of course, not always. This means that the reportorial performances are dynamic and emergently interactive. These initial understandings of both sides are “brought to the street,” where they are acted upon and strategically modified. Sometimes there occurs forcible constraint and even violent repression. This dynamic also holds regarding nonviolent protest, and it is in the protester-state dynamic that the power of nonviolent action most acutely unfolds in repressive states. Let us...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Notes on contributors

- 1 Analyzing social movements, nonviolent resistance, and the state

- PART I Nonviolence and social movements: elaborations

- PART II Nonviolence and social movements: engagements

- Index