![]()

Part I

![]()

Chapter 1

The “publish or perish” adage has been revised to “publish in English or perish” in many parts of the world. The importance of publishing in English even when that is not the researcher’s native language is seen in Asia, Latin America and Europe (Englander & Uzuner-Smith, 2013; Flowerdew, 2013; Hyland, 2015; Solovova, Vieira Santos & Veríssimo, 2018). A recent study noted that researchers in Germany, France and Spain publish more papers in English than in their national languages (Huttner-Koros, 2015). The pressures to publish research in English have grown with changing economic ideologies that prize the globalization of knowledge and the so-called knowledge economy. In this book, we discuss the research publishing world that affects nations, universities and individual researchers. Within these contexts, there are growing efforts to mount pedagogical programs that support researchers who use English as an additional language (EAL) – whom we henceforth call plurilingual users of EAL – so that they can publish their research findings in international journals. The multiplicity of such pedagogical efforts has created a burgeoning field that has been called English for Research Publication Purposes (ERPP).

We have mindfully chosen to use particular terminology throughout this book, including the term plurilingual EALs, when referring a diverse group of scholars using English as an additional language from non-Anglophone geolinguistic contexts. This choice reflects the apparent preference of those in the field who self-identify as such, challenging problematic, deficit terminologies such as “non-native” speakers of English. Next, we use the term ERPP alongside the terms “scholarly writing for publication” and “scholarly research writing.” Using ERPP is problematic as it potentially privileges English over other languages in knowledge production, thus reifying the hegemonic global position English holds. However, the term also most accurately reflects research and writing activities conducted with the express intent of fostering English language publication, something the readership of this book is likely acutely interested in. Ultimately, we hope readers of this book will recognize that, though we use the term ERPP, we do so with a keen eye on challenging the global hegemony of English and promoting plurilingual perspectives, discourses, and epistemologies in knowledge production.

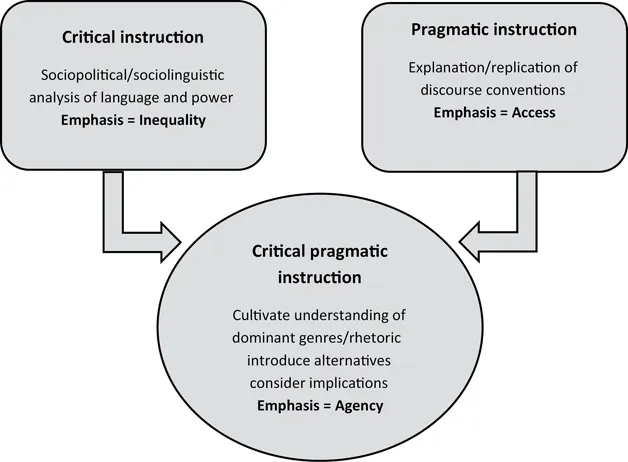

Throughout this book, we use terms such as “pedagogy,” “orientation,” and “approach” with their pluralized forms to draw attention to the possibility of multiple ways of creating and implementing teaching of ERPP. Additionally, we point out the difference in our use of these terms. An orientation informs rather than represents particular instructional approaches or pedagogies, the latter two terms we use interchangeably. It is our intent in this book to highlight critical versus pragmatic orientations that inform critical pragmatic instructional approaches to ERPP. We aim to operationalize a critical pragmatic approach by introducing a critical plurilingual framework and related pedagogies for classroom practice.

This book contributes to the field by providing an in-depth case study of one pedagogical program that is analysed within the larger context of the dominance of English in research publishing. When researchers in the field of English for Research Publication Purposes discuss other existing pedagogical programs, some call for a “critical-pragmatic approach” to the pedagogical agenda (Burgess, Martín & Balasanyan, forthcoming; Curry & Lillis, 2013; Flowerdew, 2007; Hanauer & Englander, 2013; Pérez-Llantada, 2012). In this book, we build upon these approaches to argue, for the first time in the literature, a thorough, research-driven proposal for how to deliver and operationalize a situated, critical, plurilingual approach under the umbrella of critical pragmatism. Readers of this book will come away with an exemplar of how the notion of critical plurilingualism can be foregrounded in assessing a case study of a pedagogical intervention. At least as important, readers will become equipped with a theoretically and empirically-informed basis for future design and delivery of (E)RPP instruction that can be applied and adapted to contexts beyond the examined case. Fundamentally, we substantiate the call to provide a critical-pragmatic approach to supporting plurilingual EAL scholars by establishing a theoretical framework for curricular development and classroom activities that may be adopted and adapted into new contexts. In this introductory chapter, we briefly lay out our position and our understanding regarding the impetus to publish in English.

The impetus to publish in English

In the disciplines of the sciences, and increasingly in the social sciences and humanities, value is awarded to research articles that appear in prestigious journals. Scholarly journals are considered to be the most prestigious when they are indexed in the Scopus and Thomson Reuters Web of Science databases. These are the journals that most often carry a high impact factor (note, this term is explained in Chapter 2). Almost inevitably, these are journals that publish their content in English. By publishing in English, a journal is more likely to be accepted into the prestige databases where there is a decided preference for English. The privileging of English is reinforced by gatekeepers such as Vice President James Testa of Thomson Reuters who wrote, “Going forward, it is clear that the journals most important to the international research community will publish full text in English” (Thomson Reuters, 2014, p. 12).

Recognition is awarded to scholars when publishing in a high prestige journal. This recognition occurs simultaneously at three scales. Recognition accrues to the researcher, to the institution of higher education where they work, and to the country in which that institution is located.

This phenomenon has become entrenched since the 1990s and the creation of neoliberal “knowledge” economies (Marginson, 2009). Knowledge has become a commodity (like labour and natural resources in former understandings of economy), and one means of counting this commodity is to count the number of research papers published in the prestige journals.

Because higher education institutions and countries are ranked based on their production of knowledge among other things, a researcher’s effort to publish in English should not be understood as motivated solely by a desire to disseminate new research to a wide scholarly audience, although this can be a fundamental part of their motivation. However, researchers are also motivated, even pressured, to publish in English language journals because of the effects on institutional and national prestige (Curry & Lillis, 2013; Englander & Uzuner-Smith, 2013). The dominance of English as the only highly valued language for knowledge dissemination on a global scale needs to be examined (Forsdick, 2018; Hyland, 2015; Lillis & Curry, 2010).

The effort to publish in English can be more burdensome for researchers who use English as an additional language, and who are based outside the “centre” countries of the United States, United Kingdom and so on (Ammon, 2001; Bennett, 2014; Bortolis, 2012). Writing in general is known to be more difficult and often less effective in a person’s second language (Silva, 1993). For non-native English users, writing and publishing in English at the level of research journals is, generally, a difficult endeavour that creates more anxiety and often results in less satisfaction than writing scholarly papers in the researchers’ first language (Hanauer & Englander, 2013; Pérez-Llantada, Plo & Ferguson, 2011). To respond to this perceived burden, and to boost the number of papers published by the university’s scholars and scientists, many universities around the world have implemented English writing and publication support programs. Among these supports, courses are sometimes initiated that are designed to assist emerging and established scholars who use English as an additional language in producing manuscripts that are accepted for publication in international, English-language journals.

It is against this background that we are interested in supporting scientists who seek to publish their research in English-language journals, recognizing the socio-politically situated context of plurilingual scholars – particularly those located in the world periphery and semi-periphery – as they engage in knowledge production.

Lens and orientation

As argued by Flowerdew (2007) and Hanauer and Englander (2013), a critical pragmatic approach to English for Research Publishing Purposes (ERPP) integrates two somewhat dichotomous orientations. A pragmatic orientation presumes that scholars should wholly adopt Western, English-language models of research papers and attempt to replicate these genres without discussion of the socioeconomic politics and ideology surrounding these choices (e.g., Day & Sakaduski, 2011). A critical orientation argues that scholars and instructors should consider the socioeconomic politics and ideology surrounding language choice and resist constrictive norms by facilitating fluid, dynamic language(s) use and local epistemological perspectives, thereby placing the onus on journal gatekeepers to embrace diverse and divergent forms of English language research papers (Benesch, 2001; Canagarajah, 2002a; Pennycook, 2010).

A critical pragmatic orientation to academic literacy “encourages students to assess their options in particular situations rather than assuming they must fulfill expectations. After considering options, they may choose to carry out demands or challenge them” (Benesch, 2001, p. 64). This agency awarded to writers is adopted by those who seek to define a critical pragmatic approach (see Figure 1.1); one that attempts to “synthesise the preoccupation with difference inherent in critical pedagogy and the preoccupation with access inherent in pragmatic pedagogy” (Harwood & Hadley, 2004, p. 366). It encourages international scholars to have “a critical mind set” (Flowerdew, 2007, p. 23), and at the same time, alert them “to the possible repercussions of some of the critical actions” (Flowerdew, 2007, p. 23).

While there have been calls among researchers of English for Academic Purposes and English for Research Publishing Purposes for “critical pragmatic” instruction, the means of operationalizing and delivering this approach has been largely unexplored in the current literature. We address this gap in this book. Through the close examination of scholars’ experiences in a scholarly writing for publication program, we develop a critical pragmatic theoretical framework for examining, assessing, and developing such programs with the ultimate goal of operationalizing a critical plurilingual approach to pedagogy. Falling under the umbrella of critical pragmatism, this book ultimately provides a critical, plurilingual approach to English for research for publication purposes that falls within the can be adopted or adapted by the reader into new contexts.

Author positioning

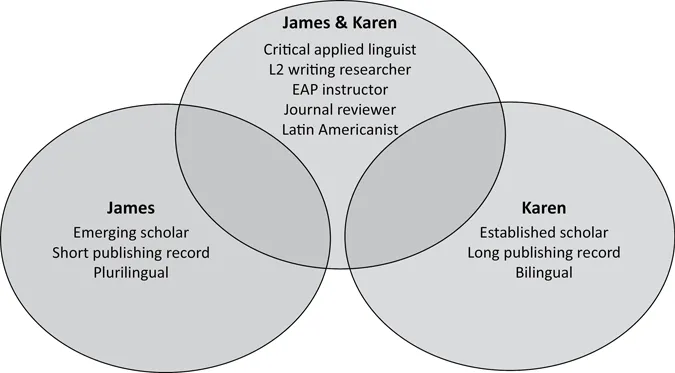

Karen, in her own words

I grew up in the United States and Canada speaking only English, despite my mother and grandparents speaking Hungarian. For some reason, my mother bought me records of children’s songs in Spanish when I was little, and perhaps that’s how my affinity for Latin America began (see Figure 1.2).

I studied how to teach English as a second language (TESOL) in the early 1980s as the field was coming into its own and taught immigrant adults and international students who came to Canada and the United States until I moved to Mexico in 1999. Living in the beautiful coastal town of Ensenada, I joined the faculty of a public university, the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, and got involved in the teacher education of future English-as-a-foreign-language students in undergraduate and graduate programs. My approach to teaching and curricular content was informed by communicative language teaching principles, social academic literacies, and, as a long-time social activist, critical pedagogy. At that time, I also started to really learn Spanish.

A critical event for me was when I received a request from the city’s scientific research institute to teach a course on how to write scientific articles in English to the institute’s researchers and doctoral students. I knew little about the area, but nonetheless, said “yes!” That began almost two decades of research and pedagogy about writing and publishing scholarly research on the part of plurilingual EAL scholars who live outside the English-dominant countries. This inquiry motivated me to enter into doctoral studies, conducted at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, where I examined how manuscripts written by Mexican scientists changed from an initial version that was criticized for its English when submitted to a journal to the later version which was then accepted for publication. Both systemic functional linguistics and second language identity theories including notions of agency and power were employed in the task.

Since that time, I have examined this phenomenon of plurilingual scholars writing for publication in English from many perspectives: language and publishing policy directives, pedagogical approaches, second-language composition processes, reception by reviewers and linguistic variation as it affects writing for publication practices. I have had the great privilege of frequently working in collaboration with colleagues of different disciplines, located in different parts of the world, and sometimes in my second language, Spanish. This research is very often informed by my critical stances. At the same time, my commitment to working with international scholars is informed by deeply held convictions of supporting access and equity so that the research and knowledge created by these scholars can be shared with the rest of the world. Thus, I also teach in programs that support emerging and established plurilingual scholars to write manuscripts in English for publication. Consequently, I have been searching for ways to perform the critical and the pragmatic ideals that more equitably support these scholars. I bear the paradox of knowing that supporting English-language publication can further endorse the hegemony of English and Anglophone paradigms and simultaneously limit the intellectual and epistemological resources afforded to other languages. I have undertaken the intellectual journey of writing this book as part of my effort to, in some small part, reconcile this paradox.

James, in his own words

I am an Anglo-dominant plurilingual scholar and educator. My teaching and research activities focus on English for academic/specific purposes. However, my interest in language owes itself more to language learning experiences in languages other than English. Building on my years of French immersion study in the sixth and seventh grades, I subsequently studied Spanish in high school (Canada) and university (United States). I started my teaching career as an English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teacher, working with adults using English as an additional language in Brazil, where I gained a high level of Portuguese fluency in the bars / cafes of Porto Alegre. During these early career years, I became increasingly aware of the asymmetrical relations of power in global English language teaching (ELT). While in Brazil, I benefited financially from my native English speaker privilege – ostensibly at the expense of my Brazilian ELT colleagues – and vowed to “cleanse” myself by researching the inextricable links between language and power. After completing an MA thesis investigating the political economy of ELT in Brazil, where I was heavily influenced by the work of critical applied linguists such as Jim Cummins, Alistair Pennycook, and Robert Phillipson, I became increasingly involved in supporting graduate students’...