1 Crowdfunding

An old story?

For centuries, creators experimented with a model collecting certain amounts of money from their patrons to pursue their new work, which is basically identical to the crowdfunding model today. In 1713, Alexander Pope, a famous 18th-century English poet and writer, set out to translate 15,693 lines of Homer’s Iliad, an honored ancient Greek poem, into English.1 Pope went through the crowdfunding model for launching this project. He crafted his pitch for attracting potential patrons for his project, saying: “This work shall be printed in six volumes in quarto, on the finest paper, and on a letter new cast on purpose; with ornaments and initial letters engraved on copper.”2 In return for appreciation in the acknowledgments and receiving the first edition of the book, 750 patrons pledged two gold guineas to sponsor his project even before he put a pen to it. It took five long years to finish the six volumes, but the reward was worth waiting: the greatest translation of Homer’s Iliad in English that has survived until to today.3,4 The patrons were listed in an early edition of the book, and it was presented to them as a reward. In addition, they might enjoy the pleasure of participating in the task of bringing a new creative work into the world. For himself, Pope could establish his absolute competitiveness among the talents of his time.

The crowdfunding model was also used in music as far back as the 18th century. In 1783, after a few years, Mozart picked a similar path as Pope.5 He had a plan to perform three new pieces of piano concertos at a concert hall in Vienna. He distributed an invitation to prospective patrons offering an earlier version of manuscripts to those who pledged – basically the same way that crowdfunding campaigns today offer contributors the chance to get the output into their hands first: “These three concertos, which can be performed with full orchestra including wind instruments, or only a quattro, that is with 2 violins, 1 viola and violoncello, will be available at the beginning of April to those who have subscribed for them.”6,7 Interestingly, like many crowdfunding campaigns today, Mozart failed on his first attempt to collect enough funding for his project. One year later he attempted again, and 176 patrons pledged enough funding to make it possible for his concertos to be performed. In addition to Mozart, Beethoven also relied upon the support of patrons for creating new pieces, for whom he provided private performances and earlier copies of works they commissioned for an exclusive period prior to their official publication.

Another early example of crowdfunding model can be found in one of the world’s most famous landmarks: the Statue of Liberty in New York.8 The Statue of Liberty was designed by French sculptor Frederic Auguste Bartholdi and financially supported by the government of France as a diplomatic gift to the United States. In 1875, due to the postwar vulnerability in France, a French politician, Édouard René de Laboulaye, proposed that the French government finance production of the statue and the United States provide the site, build the podium, and assemble pieces of the statue. By 1885, the Statue of Liberty arrived in New York in pieces, but the United States, specifically the New York government, had been unable to finance the budget for the podium and assembly of the statue. A committee named the American Committee of the Statue of Liberty was in charge of fundraising but fell apart, and New York Governor Grover Cleveland turned down using city funds to pay for it. Congress thus could not agree on a funding composition. Amid this unpredictability, other big cities, such as Boston, San Francisco, and Philadelphia, offered to settle the money for the podium in return for its relocation. New York had no feasible alternative before renowned publisher Joseph Pulitzer launched a fundraising campaign for raising $100,000 to support the project in his newspaper The New York World (The World). He promised to print the name of every contributor in The World, no matter how much amount of the money given. In five months The World raised $101,091 from more than 160,000 people, most of whom contributed less than a dollar.9 The statue could be finally dedicated on October 28, 1886.

Those projects from the old days would be representative crowdfunding campaigns among those initiated at Kickstarter if launched today. Basically, similar to the crowdfunding model, for certain projects with clear purpose, they raised money from a large pool of people; each pledged small to medium amounts of money. So, is crowdfunding today a replication of these old stories? Although there are undeniable overlaps between then and now, the crowdfunding model is essentially different from those classical practices in three aspects.

First, the internet makes the campaigns dramatically more visible and accessible to all. Most information about the projects is presented through campaign pages on crowdfunding platforms and can be shared via the web in a seamless manner. Any person can participate in supporting any campaign at minimum cost for access and transaction. More importantly, potential contributors can see the level of support from other people as well as its timing before making their own funding decisions, generating more dynamics in the crowdfunding context.

Second, relatedly to the first aspect, crowdfunding has opened up new tremendous opportunities for creators with different backgrounds, which would not have been available before the internet era. Thanks to the connected world, creators, including ordinary people with favorable ideas, can reach a circle of people who want to help each other bring creative and imaginative ideas to life. Pope, Mozart, and Pulitzer were already preeminent figures in their time before launching their own projects for raising money. Although those practices were allowed only for someone with strong profile and background in the pre-internet era, what is happening today is widening the gates for everyone who wants to expand their creativity (even for fun in some cases).

Last, crowdfunding offers something unique other funding channels do not – a way to distribute and commercialize creativity. Through a crowdfunding campaign, individual creators can tab to a community of contributors. This community may perform as supporters, beta testers, early customers, and enthusiastic fans. Crowdfunding today is much more than a simple financing mechanism that has the potential to change the landscapes of several important domains, including but not limited to production, financing, distribution, and marketing.

Although crowdfunding is still a rapidly emerging and evolving phenomenon, this book intends to highlight the changes made through crowdfunding as it exists today and the potential impacts of this phenomenon on our communities and society.

Notes

2 How crowdfunding works

Some core aspects of crowdfunding

We can find a set of definitions of crowdfunding from the previous literature. Part of the earliest literature is presented as follows:

- A collective effort by people who network and pool their money together, usually via the internet, to invest in and support efforts initiated by other people or organizations (Ordanini et al., 2011)

- Tapping a large, dispersed audience, dubbed as “the crowd,” for small sums of money to fund a project or a venture (Lehner, 2012)

- An open call over the internet for financial resources in the form of a monetary donation, sometimes in exchange for a future product, service, or reward (Gerber et al., 2012)

- An open call, essentially through the internet, for the provision of financial resources either in the form of donation or in exchange for some form of reward and/or voting rights to support initiatives for specific purposes (Belleflamme et al., 2014)

- The efforts by entrepreneurial individuals and groups – cultural, social, and for profit – to fund their ventures by drawing on relatively small contributions from a relatively large number of individuals using the internet, without standard financial intermediaries (Mollick, 2014)

There are evident common aspects across those definitions. First, crowdfunding is an initiative for fundraising. It is apparently a new type of financing approach using new channels. Second, it is conducted for a campaign of a creator. The scope of creators in the crowdfunding context is broader, including but not limited to entrepreneurs, artists, and social enterprises. Third, it raises money by collecting small to medium amounts of funding from the crowd, basically consisting of the undisclosed public. This aspect is the most distinctive characteristic of crowdfunding, distinguishing it from the existing financing models, such as VC and business angles. Finally, all transactions and communication between the creator and the crowds are managed mainly through the online platform.

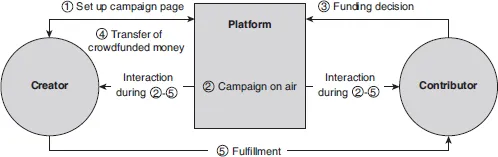

From this notion of crowdfunding, we could identify that three main players are engaged in crowdfunding. The first player is the creator, who creates new campaigns and seeks funding from the crowds. The crowds constitute the second player, contributors.1 Contributors decide whether to support the campaigns or not after considering an expected compensation from the campaigns, including intrinsic values (e.g., altruism, fun) and extrinsic benefits (e.g., rewards, relationship). The third player is the platform operator, which brings the other two players on board and provides an opportunity for exchanging values.

Most crowdfunding platforms have four common properties that are essential for enabling and promoting the transactions between two players: They are 1) a standardized format for creators to pitch their campaigns, 2) a payment system allowing a large volume of small financial transactions, 3) a display of funding progress, and 4) tools for creators and contributors to communicate with each other.

Once a creator uploads some mandatory information introducing the campaign (e.g., goal amount, funding duration, planned rewards in return for funding), and after the platform operator confirms the appropriateness of the campaign and the fulfillment of the requirements, the campaign page goes live on the crowdfunding platform. Potential contributors are exposed to the page and decide whether to pledge to the campaign before the due date, which is set by the creator. If a contributor decides to pledge for the campaign, a transaction between the contributor and the platform takes place. The record of this transaction is reflected on the campaign page as an aggregated form, including total funding amount and number of contributors to date. If the funding amount reaches (or exceeds) the goal within the designated period, the platform operator will transfer the collected money to the creator after deducting brokerage, usually 5–10% of the total amount. After the transmission, the creator fulfills the duties of developing the campaign and delivering rewards to contributors as proposed. In the case of funding failure, on the other hand, the platform operator typically cancels all the transactions, indicating that there will be no financial loss to the contributors. Some crowdfunding platforms allow creators to keep all funds regardless of reaching the goal amount, but the major platforms still transmit the funds raised to creators only if they meet the goal amount.

The whole crowdfunding process is represented in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 Crowdfunding process

Crowdfunding as a two-sided platform

The two-sided platform (TSP) is a marketplace that enables direct transactions between two distinct types of affiliated customer groups between which cross-network externalities exist. Although the TSP is a tool for facilitating transactions (Eisenmann et al., 2006; Hagiu and Wright, 2015), it canno...