![]()

1 Foundations for Picturing Human Forms

Conventions, Historical Context, and the Confluence of the Fine and Applied Arts

Like text, pictures never materialize in a vacuum but, rather, in complex social, cultural, and disciplinary settings in which pictorial conventions are invented and in which they develop and evolve. Pictures talk to each other in visual conversations that sometimes continue over long stretches of time and space. However aware their audiences might be of these interactions, they profoundly shape the processes of creating and interpreting pictures. A picture of someone changing a cartridge in a laser printer has its visual antecedents in earlier instructional pictures, decades or even centuries before—perhaps all the way back to when practical pictures first appeared in print in the sixteenth century. And that same picture has its progeny in some future image, digitally rendered and displayed, showing how to operate, no doubt, some yet unknown piece of equipment or technology.

So when taking the longer view of how applied images of people emerged and function today, we need to interrogate the historical record to determine how these images relate to those that preceded them, including those in the fine arts, mainly painting and drawing, where both technical and aesthetic innovations shaped practical picture-making. We also need to identify the recurring purposes of envisioning people in practical images—to create scale for viewers, instruct them, persuade them, foster trust, and so on. And we need to identify and trace the lineage of conventions for envisioning human forms—gestures, the positioning of the body, its level of abstraction, its impersonalization—all of which contemporary audiences have come to expect.

The Confluence of Fine and Applied Arts

The genealogy of practical pictures with human forms includes not only other such practical pictures but also those considered fine art, with which practical representations have intermingled extensively, particularly during the modernist era with its emphasis on functional, machine-age forms. Even the drawings created by engineers, Eugene Ferguson claims, have an affinity with those of artists, both in terms of decision-making and adherence to stylistic norms (23). The interrelationship between applied and fine art pictures poses two questions: Which of the two takes precedence in visualizing human forms, and which in interpreting them? The second question is more complex, given that in everyday contemporary life we are more likely to encounter an applied form—in a car owner’s manual, infographic, or elevator emergency sign—than a painting hanging in a museum or reproduced in a book or online gallery. I address this question later when I discuss drawing conventions and audience expectations.

With respect to the first question, we probably assume that the fine arts take precedence in shaping visual representations of human forms, based on cultural status, scholarly attention, and the sophistication of the images, not to mention the genius and technical skill of the designers and artists that created them. Despite the burgeoning interest in popular culture and the dissolution of boundaries between “high” and “low” culture, we take it as axiomatic that fine arts representations differ markedly from—and probably surpass—those that have practical applications, given the originality and aesthetic proclivity of the fine arts and their status oftentimes as museum artifacts, valuable commodities, and progenitors of other such works. Moreover, why would Raphael or Rembrandt squander their talent on applied forms when they could aspire to greater heights aesthetically and secure their immortality in the pantheon of master painters? As a result, we assume that the fine arts operate on a different plane than applied forms, standing atop a hierarchy of visual representation and guiding and shaping their less-worthy kin below.

Still, the gulf between fine and applied representations may not always be as vast as we might first imagine, partly because practical subjects have long been the focus of representation, even from the earliest picture-making. Early prehistoric pictures with human forms envisioned practical tasks—for example, a painting in the Lascaux Cave in France that shows a human form with animals and later wall paintings in Anatolia (Turkey) that envision human figures extensively in hunting scenes (Davies et al., 2–6, 13–14). Ancient Sumerian, Assyrian, and Egyptian reliefs visualize military battles (Davies et al., 27–28, 37, 50–52, 68–69), as did Greek urns and Roman triumphal arches and columns, such as the expansive narrative visualized on the Column of Trajan (and later the Bayeux Tapestry). Agricultural scenes with human figures, especially those shown domesticating animals, were also frequently visualized in ancient art, often predating representations with primarily expressive, religious, or aesthetic purposes. Many of these representations of practical subjects had an explanatory purpose, if not also instructional value, suggesting that ancient art had a strongly applied orientation in which human forms consistently played a key role.

The genealogy of picturing human forms in the modern era from the Renaissance to the present is, by comparison, more detailed and transparent because the visual artifacts are far more plentiful and accessible. To trace this genealogy, we might interrogate the relationship between fine arts and applied representations in three ways:

- By examining fine arts pictures that visualize practical subjects in science, technology, industry, and business.

- By tracing stylistic affinities between the two realms, in terms of both aesthetics and visual conventions.

- By identifying artists and designers that visualize human forms in both fine and applied representations.

Because these three issues frequently overlap, I discuss them simultaneously rather than individually, tracing several developments from the Renaissance through modernism, including the early emphasis on classical human forms, the democratizing effects of Enlightenment values on visual representation, the evolving relationship of human figures with nature, and the modernist quest to universalize human forms. Each of these developments has influenced how human forms have been represented in both fine arts and applied pictures, illustrating the long-standing confluence between these two modes.

Envisioning the Classical Human Form

The archetypal nexus of fine and applied pictures, of course, can be found in the work of Leonardo da Vinci, who rendered the human figure for expressive, aesthetic, and functional purposes. In Figure 1.1, for example, Leonardo’s Ginevra de’ Benci (1474–78) shows his exquisite method of portraiture that captures both the external and internal attributes of his subject: a young, intelligent woman of serious disposition, revealed by her dignified posture, intent eyes, restrained smile, and simple but elegant clothes. Her long neck, gold hair, and fine, light skin amplify her striking and virtuous demeanor.1 Altogether, this combination of attributes establishes her as a distinctly singular individual. At the same time, the picture renders her according to the cultural and aesthetic conventions of her time and place: figural elements with the parted hairstyle, curled locks, headdress, and laced blouse, and contextual elements in the space around her with the stylized vegetation, idyllic landscape, and distant church spires—all of which firmly situate this picture in the Italian fifteenth century. So Leonardo renders a highly distinct figure with a unique personality that’s simultaneously immersed in the collective conventions for picturing people at this historical moment. That historical moment was shaped by the revival of classicism in all the arts—epitomized in paintings visualizing scenes from the Bible and from Greek and Roman myths and coalescing in vernacular figures like Leonardo’s Ginevra de’ Benci and the idealized landscapes in which such figures dwelled.

Figure 1.1 Leonardo da Vinci’s late fifteenth-century portrait Ginevra de’ Benci. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington. Alisa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Leonardo Da Vinci also drew on the classical tradition in integrating human figures into his applied pictures, such as his visionary sketches of military machines.2 In these conceptual drawings, Leonardo envisions human forms in various poses and dress as they engage with potent, lethal machines. For example, in his Design for a Giant Crossbow (Zöllner and Nathan 628–29) a lone human figure, dwarfed by the mechanical device, acts as the heroic agent triggering its operation. In Leonardo’s drawing of a Scythed Chariot (Zöllner and Nathan 634–35), a warrior atop a horse operates a deadly mechanical apparatus, its rotating blades mowing down writhing victims, grotesquely persuading readers of its efficacy. The gruesomely persuasive appeal of the picture depends entirely on the human forms, both the victorious hero who operates the device and the disembodied figures that suffer its brutal effects, which give the picture its rhetorical force. In Leonardo’s drawing Study with Hoist for a Cannon in an Ordnance Foundry (Zöllner and Nathan 119), a swarm of naked bodies hoists a cannon onto its frame for transport into battle. The figures engaged in these herculean labors fit the classical paradigm of celebrating the human form, bizarre as the appearance of nude figures in a military drawing may seem today. Given that interpretive divide, we can only speculate about Leonardo’s rhetorical intentions: maybe he wanted to show more clearly the bodily positions and strength required for such tasks or wanted to contrast the fragility of the human forms with the potency of the weapon they wielded, which might persuade audiences that his technical ingenuity could greatly empower them.3

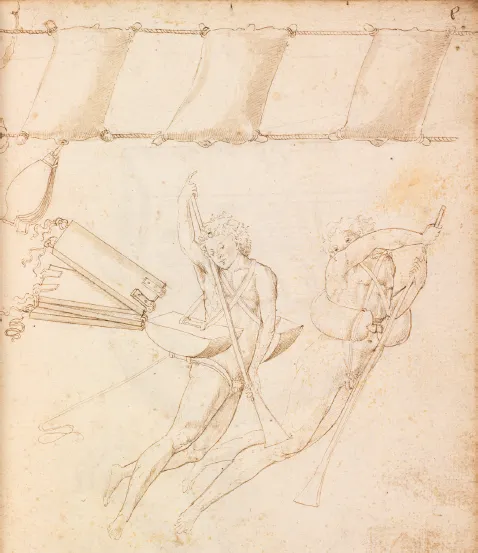

A similar approach to integrating human forms into practical subjects appears in a few of the drawings in Francesco Martini’s late fifteenth-century collection Edificij et Machine, which visualizes mechanical devices for both domestic and military purposes. Figure 1.2 shows two nearly nude figures partially submersed in water deploying a flexible bridge: the top of the picture shows pouches that are inflated with bellows and strung together with rope, while below these (on the left) appear a series of rigid steps on hinges. The figures are equipped with flotation devices and paddles so they can complete their tasks efficiently as they propel themselves through the water. Another drawing from Martini’s Edificij et Machine shows three nude figures navigating water, two of them by standing on flotation devices and another by sitting on an inflated sack. Of course, given the watery context of these activities, barely clothed bodies might be practical for these tasks; more than likely, however, like Leonardo’s, these figures represent drawing conventions of the period, where human forms were modeled on classical ideals and the humanistic aspirations they fostered, manifested here in the interaction of these figures with new technology.

Figure 1.2 Francesco di Giorgio Martini’s late fifteenth-century drawing of figures deploying a portable bridge. Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

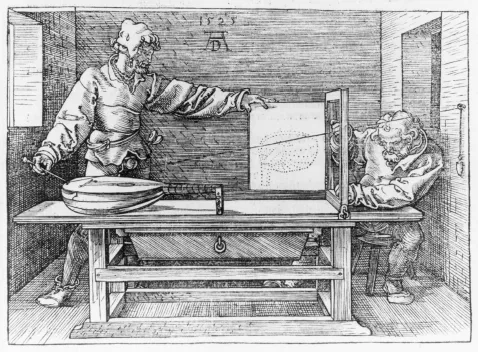

Visualizing human forms with the emerging conventions of the Renaissance entailed rendering them as full three-dimensional objects, a process that required new and advanced techniques. Albrecht Dürer instructed artists and designers in these new practices with his drawing of a perspective device Draftsman Drawing a Lute (1525), which appears in Figure 1.3. By looking through a grid frame, an artist can create a perspective drawing by plotting data points from a given object. On the left side of Dürer’s picture an artist locates a point on the object of study, a lute, while the figure on the right holds a string line to show where that point is positioned on the grid. In the center of the picture the artist holds a paper showing the transcription of the data points, a radically foreshortened image typical of early Renaissance perspective. Significantly, Dürer chose a musical instrument as his example in this picture: musical instruments in art often evoke human (especially female) forms, and perhaps Dürer wanted a less provocative alternative to his famous drawing of the perspective device featuring a reclining nude woman (Knappe 373). So in this picture with the lute (and its companion with the woman), the artist and his assistant instruct audiences in the practical techniques of geometrical projection, primarily for drawing human forms, envisioned directly or metaphorically. Dürer himself applied these perspective techniques in illustrated treatises in which human figures played a central role—for example his manual (Fechtbuch) on fencing and military combat, which included a series of pictures with figures illustrating fighting techniques.

Figure 1.3 Early sixteenth-century perspective drawing device illustrated by Albrecht Dürer. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [LC-USZ62–123456].

The pervasive influence of these drawing techniques, and the classical ideals that drove them, can be found in figures in early engineering books, among them Georgius Agricola’s De Re Met...