eBook - ePub

Food and Age in Europe, 1800-2000

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Food and Age in Europe, 1800-2000

About this book

People eat and drink very differently throughout their life. Each stage has diets with specific ingredients, preparations, palates, meanings and settings. Moreover, physicians, authorities and general observers have particular views on what and how to eat according to age. All this has changed frequently during the previous two centuries. Infant feeding has for a long time attracted historical attention, but interest in the diets of youngsters, adults of various ages, and elderly people seems to have dissolved into more general food historiography. This volume puts age on the agenda of food history by focusing on the very diverse diets throughout the lifecycle.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Food and Age in Europe, 1800-2000 by Tenna Jensen,Caroline Nyvang,Peter Scholliers,Peter Atkins,Peter J. Atkins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

Food, age, and the life course in Europe, 1800–2000

What we as individuals eat is not constant over the duration of the life course. The continuous changes in diet and food intake result from our altering biological needs and abilities as well as from cultural and societal perceptions of what is appropriate for a person to eat and drink at a given stage in life. Interest in the various life stages goes back a long time, as mid-seventeenth-century drawings clearly illustrate (Figure 1.1). These pictures show the fascination for the ‘ascent’ and ‘descent’ during a lifetime, depicting the transforming body and changing activity per decade. These drawings ignored the relation between age and diet, however, and this should not come as a surprise. Infant food was not an issue because breastfeeding provided all that was needed – at least, that was the expectation – while the diet of (young) children resembled that of adults in smaller quantities, and therefore required no particular attention. The only link between food and age pertained to elderly people, albeit modestly. For example, in Europe elderly people were advised to drink wine, which was good for their health and brought joy.1 Such recommendations referred to Claudius Galenus’s (c. 129–c. 200 C.E.) influential and tenacious views: elderly people should have a warm and moist diet.2 Neglect of toddlers and children and an elusive interest in old age persisted until the mid-nineteenth century, when, very gradually, distinct diets were conceived for the newly born (particularly where bottle-fed), pregnant women, workers, the sick and other specific categories.3 It is only in recent decades of our own era that the relationship between the biological and cultural reality has received growing attention from scholars within the social sciences and humanities and spurred on a range of new research themes and fields, e.g. gender studies, studies of bio-politics and cultural gerontology.

The aim of this book is to expand the field of food history by providing insights into the historical relationship between different life stages and the politics, consumption and practices of food in Europe during and after industrialisation. In this way the book not only broadens our understanding of the relationship between life stages and food, but also of how the industrialisation and urbanisation of Europe has affected the living conditions of minority groups such as infants, children and older people.

Figure 1.1‘The staircase of ageing’, c. 1650

Source: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Anonymous, c. 1650 (www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/collectie/RP-P-1937–1901)

Age(ing)

It was only in the 1960s that social scientists began to engage in numbers with the topic of ageing, responding to longer life expectancies and to predictions about the consequences for the demographic profiles of Western societies. Since then, there has been a surge of work in the multi-disciplinary field on ageing that has grown around the so-called ‘life course perspective’ (LCP).4 Although research in this vein has been broad ranging, codifications of methodology and supporting theory have been lacking until recently.5 Nevertheless, scholars have identified added value in looking at human development in the long run, in contexts such as life events, social groups, locality and periods of social turmoil.6

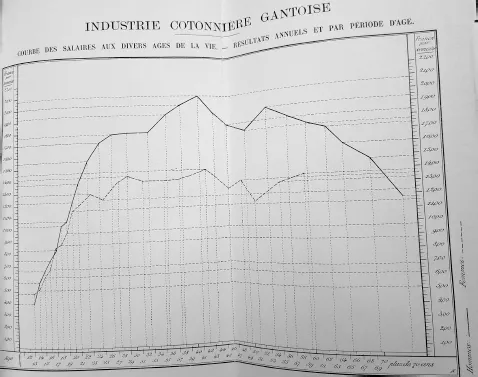

Life-course theory deals with the factors that influence the trajectories of human lives. The biographies of individuals are seen historically as emerging from the intersection of events and continuous processes.7 Gilchrist puts it well when she views the life-course approach to history – in her case the archaeology of the medieval period – as the ‘exploration of the conjunctions between phases of human life’. But, ‘rather than studying successive episodes or stages of the life cycle in isolation, the approach stresses the inter-linkages between phases of life and provides a framework for examining the distinctive experiences of individuals at respective stages of their lives’.8 Social history has provided examples of integrating a person’s consequent life stages. Inspired by studies of, among others, B. Seebohm-Rowntree and L. Varlez around 1900, historians investigated the labour and wages of household members according to the age of the ‘head of the family’, to find a direct connection between, on the one hand, his fluctuating income and, on the other, the participation in wage labour and contribution to the household income of his wife and children.9 This research demonstrated the direct bond between the life course of the individual within the household, showing important variations of income, and thus living conditions over the life cycle. Particularly when reaching 50 years of age, income was said to collapse (Figure 1.2). This research fits within the historiography of the family and survival strategies.10 Confronted with changes over the life cycle, the historian can only hypothesise about consequences on the diet of fluctuating income and changing composition of the household.

If we accept the relevance of the life-course perspective, is the study of ageing then about old age? The simple answer is no.11 There is far more to it than that. While gerontology and its cousin, geriatrics, have made valuable insights, particularly with regard to medical interventions and practical, institutional policies, the ageing life-course perspective is seen as under way throughout the whole lifespan. As yet, it has to be said that enthusiasm for this departure has been noticeably less amongst historians, and life-course literature is especially sparse in the sub-branch of food history, the field of this book. While we can justifiably say therefore that our collection of essays is breaking new ground, we do not claim that our reach is comprehensive. On the contrary, at the end of this chapter we will point to some of the many remaining knowledge gaps and make some suggestions for an agenda of possible future research.

Figure 1.2 Income of male and female textile workers according to age, Ghent around 1900

Source:Varlez 1901, 80–81

Food

Adult diets have been studied since the first quarter of the nineteenth century, with a view to increasing work capacity and reducing nutritional cost. Infant feeding caught the interest of nutritionists since the middle of that century (to reduce mortality), and adolescent foodways were investigated from around 1900 to ensure an adequate labour force for industry and the army.12 Recently, food has entered the scope of gerontology and geriatrics, as testified by the existence of highly specialised journals such as the Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly, 1980–2010 (renamed Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics, 2011–). Together, the concept of the ‘elderly’ became more complex, in that age cohorts emerged (such as the ‘young elderly’). Moreover, since the 1990s, a life-course perspective related to food has sought attention.13 The insights of gerontology reveal that elderly people eat more conservatively, need more salt and sugar because of a loss of gustative capacity and, in general, are anxious about eating out.14

This literature has inspired food history writing.15 Yet, a debate about the relevance of a life-course perspective to food history would be helpful. We can see both advantages and disadvantages. We can begin with a strand of work on food choice in nutrition science and psychology that has profound implications for food history. Carol Devine and her colleagues have published extensively on this theme in a way that values the temporal dimension. Their version of the life-course approach has been to analyse food preferences in stasis or change for sample groups of respondents through time.16 An example is what they call ‘food choice trajectories’ of particular foodstuffs, finding influences from historical events (period effects) and cohort effects.17 The awareness of time includes time itself as a resource, because the shortage of time in the accelerating pace of our modern lives means reduced availability for food preparation, for the contemplation of healthy ingredients and for eating en famille.18

There is less time in modern lives for food preparation, and new technologies, such as the microwave and frozen ready meals, have facilitated this long-term trend. Coupled with social changes such as women’s growing participation in the workforce and the trend for eating out, these amount to profound historical shifts.19 An example is the emergence of food habits that reflect the ecological variables bearing upon an individual at a formative period of live.20 Growing up in the 1950s, for instance, Peter J. Atkins remembers his mother telling him to eat everything on his plate and to ‘think of the starving children in China’.21 This was a reference to food shortages during the Maoist Great Leap Forward in that country. To this day he clears his plate, whereas his five grandchildren, living in an era of abundance and waste, have a different attitude, especially to anything that does not appeal to their taste buds. Martin Franc, in his chapter in this book, makes it clear that food habits arising out of austerity in post-war Czechoslovakia persist among the older generation, many of whom are even nostalgic about particular foods that were served in school canteens in the 1960s, even though they know that these were cheap and of low quality.

As Devine notes, the life-course perspective includes many notions of time that are potentially useful in understanding food choice, including ‘trajectories, transitions, turning points, lives in place and time, and timing of events in lives’.22 This tends to be work with living subjects, and the closest Devine comes to a historical viewpoint is in identifying what she calls ‘retrospective studies’. For her, a ‘historical perspective’ is about looking at the changing food system contexts in which food choice takes place. In other words, this is a high-level tension between supply-side factors of availability and price and demand from individuals and groups with their own preferences and consumer capacities.

We beg to differ. The ICREFH view of food history is more comprehensive and highlights interest in cultural aspects. For a long time, ‘society’ has developed clear views on what people of various age ought to eat and drink, including food avoidances and taboos,23 while in the early nineteenth century, dieticians avant la lettre started to envisage the ideal diet of particular age categories (primarily, babies). Moreover, people themselves have clearly assessed their own foodways according to age. These cultural constructions are integrated into ICREFH’s concerns that deal with age, which implies the usage of particular sources, methods and approac...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- List of tables

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction: food, age, and the life course in Europe, 1800–2000

- Section 1 Infants

- Section 2 Children

- Section 3 Adults and older people

- Index