![]()

Part I

Two American Artists and Silent Cinema

![]()

1 Lust for Looking

John Sloan’s Moving Picture Eye

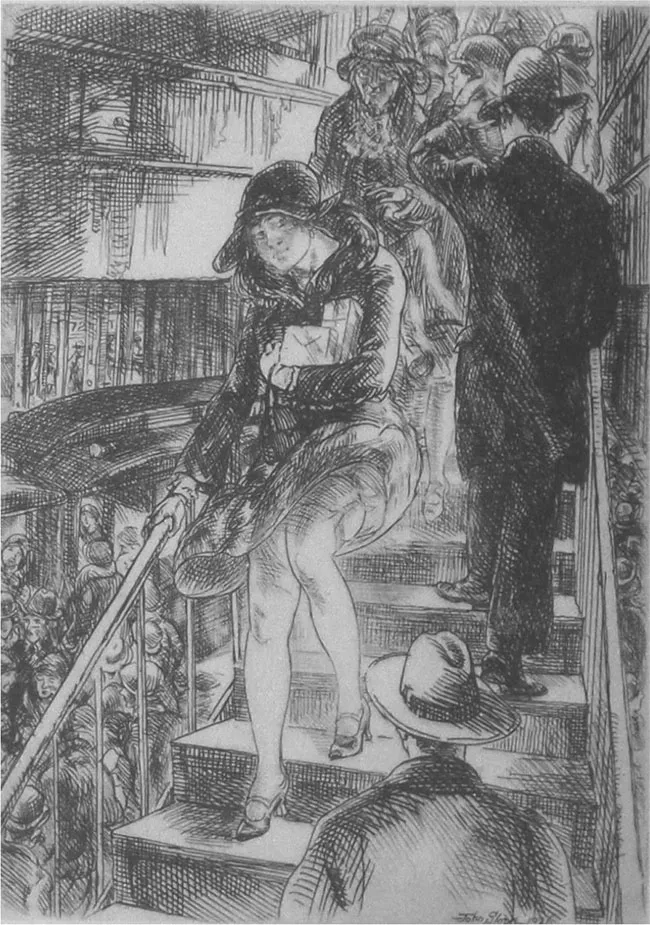

Marilyn Monroe was standing atop a subway grate when an updraft sent her diaphanous dress flaring, and became an icon of movie glamour in 1954. A quarter of a century earlier John Sloan created the prototype when he etched the figure of a woman descending the steps from the elevated train, her skirt caught by the wind to expose an immodest extent of leg (Figure 1.1).

Its title Subway Stairs looks forward to Marilyn as well as backward to his old hero Thomas Rowlandson, whose watercolor Exhibition, Stare-Case (1811 (?), Courtauld Institute, London) featured the lively interaction of voyeurs and exhibitionists at London’s Royal Academy. Together the artists are poking fun at the viewer who is, of course, caught in the act of staring up at a suddenly revealed bit of female anatomy. As was his habit, Sloan nods to the art of the past while simultaneously looking to modern sources – in this case to cinema. The subject was an old standby of the movies, captured in an Edison film of 1901 entitled What Happened on Twenty-third Street, New York City. This privileged venue for Peeping Toms was at the bottom of the street where Sloan lived; “a high wind this morning and the pranks of the gusts about the Flatiron Building at Fifth Avenue and 23rd St. was interesting to watch,” the artist confided to his diary.1 So we know he was among male spectators who gathered there and were routinely chased away by the police – a ritual that gave rise to the phrase “Twenty-three Skidoo.”

Sloan’s series of etchings entitled New York City Life was created in dialogue with early film. The series was his first major project after relocating from Philadelphia to New York in 1904. New York City Life consists of ten prints – each measuring approximately 5 x 7 inches – that allowed the viewer equal access to his neighborhood’s public streets and private dwellings at intimate moments. There was nothing much like this series in American art at the time. Realizing that that was over 100 years ago, we feel renewed admiration for Sloan’s ability to capture his urban environment in this etching sequence. This achievement was related to what might be called Sloan’s moving picture eye. Sloan, at age 25, had been in the audience when the earliest silent films were shown in Philadelphia and became a regular moviegoer after settling in New York.2 His art evolved in tandem with the new medium.

New York City Life

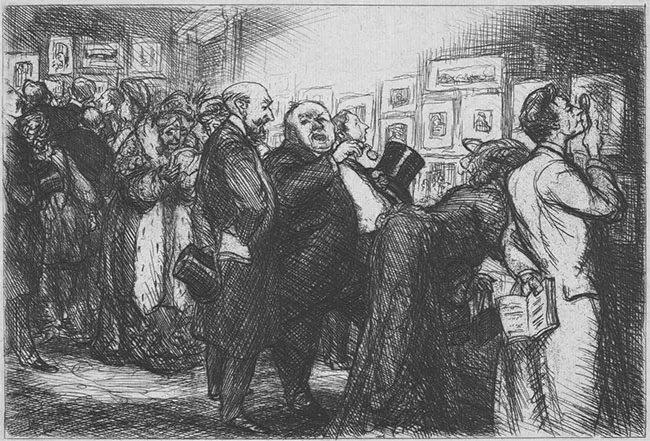

Sloan opened his series with the finely executed etching Connoisseurs of Prints (Figure 1.2) depicting a print show at the old American Art Galleries on Twenty-third Street. He arranges the attendees according to states of attention and expertise, from the undifferentiated group at the back of the room to the model connoisseur with gallery guide and magnifying glass in the foreground. Sloan is holding these characters up to mild ridicule – including the taller, baldheaded connoisseur at the center who surreptitiously directs his gaze at the backside of the woman bent forward for optimal viewing. Right from the first print in his New York debut series, the artist is challenging the public: critiquing the concept of the specialist’s eye as well as institutionalized modes of perception.

In the remaining nine prints, Sloan leads us out the door of the gallery and through the nearby streets, where frame-by-frame he creates a dynamic portrayal of his neighborhood. The next etching humorously calls attention to a pair of Fifth Avenue Critics, identified by the pince-nez one elder woman fingers at her chest, ready to raise them for closer inspection. She and her companion are ensconced in their open carriage, feeling superior to the attractive younger woman who is about to alight from the opposite conveyance, its closed cabin indicative of her more clandestine – and, they judge, disreputable – purpose. Sloan does not let them get the better of her, though, for he slyly inserted the sign “Antiques” over the critic’s head, branding her notions Victorian but also reminding us of rapidly changing modes of vision.

Sloan initially titled this etching Connoisseurs of Virtue, indicating his original intent to create a series of connoisseurs. It is generally assumed in the scholarly literature that he abandoned the connoisseurs project after this.3 I maintain, however, that it merely metamorphosed into a more ambitious project. Broadly defined, the “connoisseur” is one who knows – more specifically in this case, a person competent to appreciate art. In 1905 the connoisseur would have been respected for her or his ability to judge by looking, for the cultivation of a “good eye.” Spectatorship in the modern city, Sloan was realizing, required equal expertise. So this first New York project grew into an extended meditation on the act of seeing in that city, on looking and being looked at: connoisseurs of urban vision.

In the early years of the twentieth century, Sixth Avenue northeast of Greenwich Village acquired a reputation that rivaled that of the Bowery. When the notoriously corrupt Police Captain Alexander “Clubber” Williams was transferred to the West Thirtieth Street Station in 1876, he was supposed to have said, “I’ve been living on chuck steak for a long time, and now I’m going to get a little of the tenderloin.” And so it was christened the Tenderloin – the area west of Sixth Avenue from Forty-second to Twenty-third Street, more or less. In its heyday from 1876 to 1915, it was home to gambling establishments, sexual services, drinking saloons and opium dens – but more upscale than the Bowery versions, and not quite so dangerous.4

This locale, curiously, is where Sloan settled with his new bride, Dolly. In September 1904 they moved into a fifth-floor walkup at 165 West Twenty-third Street, where they remained for almost seven years, until May 1911. Artists then as now gravitate to low-rent districts, but in 1904 there were other, more respectable areas where Sloan could have set up housekeeping just as cheaply. Why here? Aside from the obvious “attractions” just enumerated, it was also part of the city’s – and the country’s – entertainment district. Kinetoscope parlors and storefront movie houses dotted the blocks while cameramen filmed movies on its rooftops and streets (as etched by Sloan in The “Movey” Troupe of 1920). Let us imagine Sloan exiting the door of his building and heading down the street. He would pass the Eden Musée, the former waxworks that became the city’s first location for continuous movie exhibition, and Koster and Bial’s, a glorified concert saloon turned movie house, as well as Proctor’s Theater.5 He made numerous circuits on foot around the neighborhood and into those theaters as he kept an eye out for promising subjects. Not surprisingly, Sloan became one of the first American artists to engage with film in a serious and sustained way.

That engagement had begun in 1896 in Philadelphia with an opinion piece he published following the screening of the Edison film The May Irwin Kiss.6 After that, he was hooked, witness to each stage of film’s development. This spanned everything from the short projected movies in between live acts in vaudeville theaters to the makeshift storefronts where movies were shown one after another and where Sloan frequently dropped in. After 1906 nickelodeons sprang up, featuring movie shows all day long and adding more fictional films, and Sloan documented this phenomenon in his 1907 canvas Movies, 5 Cents (see Figure 1.9).

Scholars have recognized the relationship between Sloan’s art and film, particularly with respect to what they identify as his interest in popular entertainment, spectatorship and objectification of the female body.7 I aim to steer the discussion in other directions, toward the evolution of his urban looking and its overlap with modern American picture making and film. The general trend in the literature has been to discuss a few of these prints together with paintings that were done several years later. But in my view the original ten etchings must be treated as an indivisible unit, for Sloan refused to exhibit or sell the prints singly. The modern city, film practice and Sloan’s art were all rapidly evolving in the early twentieth century; beyond Sloan’s protestations about the integrity of his series, we need to zero in on visual practice specific to 1905 and early 1906. The City Life series maps the complexities of visual attention that immediately confronted the artist when he moved to Manhattan. The prints delivered a real jolt to the public when they were exhibited together in 1906, and we should try to recapture some of the excitement they stimulated.

Art from Life – Movie Pictures

Georges Méliès in France and Edwin S. Porter in New York were making the most popular movies at the time. Coming to cinema from a background in magic and the theater, Méliès created movies like the renowned A Trip to the Moon (Le Voyage dans la lune) of 1902. Scrutiny of his work reveals that he showed objects and actors first in one position, then in another; he filmed one frame, stopped the camera, and then set up the next frame. Porter, by contrast, perfected a unique moving picture style by closely following his characters as they moved about. In How They Do Things on the Bowery, Porter for the first time applied the mobile camera associated with actuality production to fiction filmmaking. Headquartered at the Edison Studios on West Twenty-first Street, he frequently followed his characters and filmed in surrounding areas – the very streets where Sloan sketched ideas for pictures.8

Much has been written recently about the ways in which the individual is bombarded with stimuli of every sort in the modern city, his or her attention tugged in a variety of directions.9 Today we have our own ways of dealing with these competing forces, but around 1900 – as skyscrapers rose, electric signs appeared and traffic sped up – people demonstrated a response specific to that moment. Sloan thought long and hard about matters of vision, about looking at the life of the city around him, about looking at pictures – both still and moving. He discovered in cinema a means of structuring his experiences of the city. This cinematic mode of vision, if y...