eBook - ePub

The Neurotic Paradox, Vol 2

Progress in Understanding and Treating Anxiety and Related Disorders, Volume 2

- 282 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Neurotic Paradox, Vol 2

Progress in Understanding and Treating Anxiety and Related Disorders, Volume 2

About this book

This collection of David H. Barlow's key papers are a testimony to the collaborative research that he engendered and directed with associates who now stand with him at the forefront of experimental psychopathology research and in the treatment of anxiety and related disorders. His research on the nature of anxiety and mood disorders resulted in new conceptualizations of etiology and classification. This research led new treatments for anxiety and related emotional disorders, most notably a new transdiagnostic psychological approach that has been positively evaluated and widely accepted. Clinical psychology will benefit from this collection of papers with connecting commentary.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Neurotic Paradox, Vol 2 by David H. Barlow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Abnormal Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Nature, Diagnosis, and Etiology of Anxiety and Related Disorders

Article 13

Disorders of Emotion

Center for Stress and Anxiety Disorders. State University of New York at Albany

A new preliminary model of emotional disorders, derived from basic tenets of emotion theory and new developments in cognitive science, is presented. It is suggested that tightly organized basic emotions stored in memory fire inappropriately on occasion. In individuals who are vulnerable both biologically and psychologically, these emotions may become the focus of anxiety or dysthymia in that the emotions themselves are experienced as uncontrollable and threatening with adequate coping being difficult or impossible. Early experiences with lack of control over one’s environment as well as biological vulnerabilities may well determine whether or not one becomes anxious/dysthymic over the experience of basic emotions in an inappropriate context. This model is illustrated in the context of panic disorder and then extended to depression (sadness/distress), stress (anger), and mania (excitement).

Anxiety and mood disorders are fundamentally emotional disorders. Therefore, the study of anxiety, depression, and other affective states, both normal and pathological, falls within the more general purview of the study of emotion. For this reason, it is surprising that investigations of emotional disorders have only recently begun to consider some of the rich traditions in the study of emotion. The purpose of this article is to present, in summary form, a new model based in part on the accumulated wisdom of emotion theory including new and exciting developments in the area of cognitive science. I begin by considering the nature of panic and anxiety. I then review depression, taking into account evidence for the very close connection of anxiety and depression. I conclude with a look at other closely related emotions and emotional disorders that have received somewhat less attention.

Panic

Within the anxiety disorders, the most profound development in the past decade in terms of its impact on research and clinical practice has been the emergence of the phenomenon of panic. Panic attacks are typically described as sudden bursts of emotion consisting of a large number of somatic symptoms and thoughts of dying and/or losing control. On the average, these symptoms are relatively consistent across people experiencing panic; however, individual panic attacks may present with a different “mix” or number of symptoms and may vary in intensity. A prominent feature of many of these attacks as they present in the clinic is the report by the client, at least initially, that no frightening situation or thought process (cue) was associated with the attack. Clients may also report the attack to be totally unexpected. Although the uncued, unexpected nature of panic attacks is clearly a construct of the client (i.e., cues are usually discovered after a systematic examination; Barlow, 1988), this phenomenon has resulted in the labeling of these attacks as spontaneous. Of course, panic attacks may also be expected and have cues, as with the specific phobic who is afraid to cross bridges (cue) and fully expects to panic if he or she must cross a bridge. These cued expected panic attacks are essentially similar in their presentation to “spontaneous” attacks (Barlow & Craske, 1990).

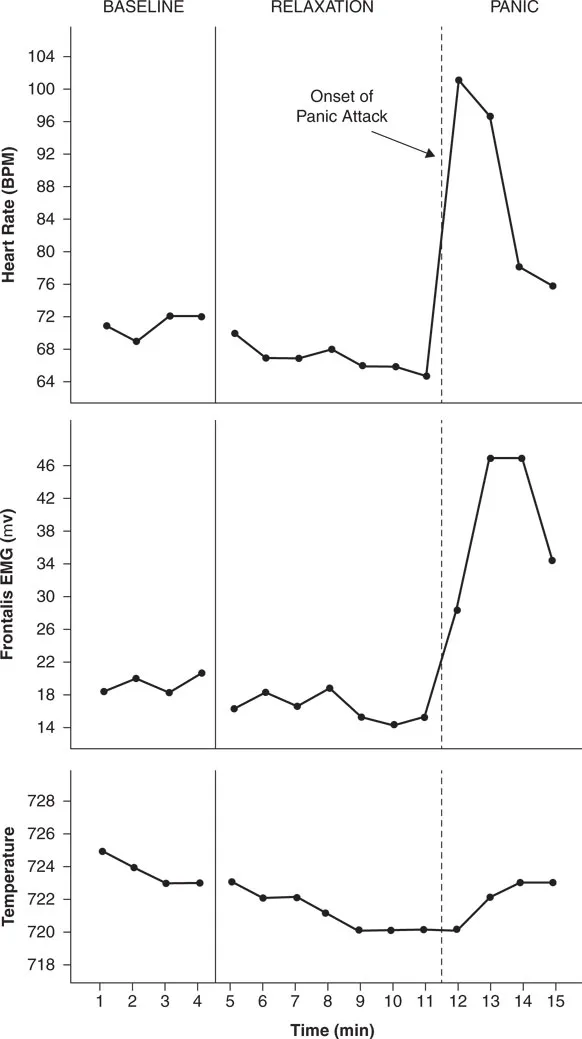

Several years ago, my colleagues and I recorded detailed physiological changes preceding and accompanying “uncued, unexpected” panic attacks in two clients who happened to be undergoing physiological assessments at the time (Cohen, Barlow, & Blanchard, 1985). An example of physiological changes associated with one of these attacks is presented in Figure 13.1.

A major goal of research over the past 3 to 6 years has been to discover the causes of panic. Given the preliminary nature of this undertaking, it is no accident that most of our ideas are simplistic. As is often the case in the early investigation of psychopathological phenomena, initial conceptualizations are one dimensional. These models may contain a grain of truth but generally espouse a linear model of causation with the emphasis on one discrete causal event. In the study of panic the most prominent one-dimensional conceptualizations specify either biological or cognitive causation.

Early biological conceptualizations of panic assumed a discrete biological dysfunction as a causal mechanism. The search for this biological dysfunction has ranged far and wide during the last decade across both central and peripheral mechanisms. The most popular procedure in this quest has been the pharmacological provocation of panic attacks in the laboratory. Substances such as lactate, yohimbine, isoproteronal, carbon dioxide, and caffeine have all been used to provoke panic. During these procedures investigators have examined several neurobiological processes such as neurotransmitter action and, more recently, patterns of cerebral blood flow (e.g., Reiman et al., 1986; see Barlow, 1988, for a review). Nevertheless, despite a number of interesting findings emerging from these studies and the promise of more to come, no evidence has been forthcoming for a discrete biological marker of panic. Rather, any number of provocation procedures, many with fundamentally different biological actions, are capable of provoking panic in the laboratory.

Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that psychological provocation procedures are also capable of provoking panic including the very interesting and seemingly panic-inhibiting procedure of relaxation (Adler, Craske, & Barlow, 1987). In this regard, one will notice that the assessment procedure in effect in Figure 13.1 that was associated with a “spontaneous” panic was relaxation. Recent studies have also demonstrated very strong effects of psychological manipulations on biological provocation procedures such as carbon dioxide inhalations (Sanderson, Rapee, & Barlow, 1989).

Figure 13.1 Physiological Changes from the Start of the Recording Session Through the Onset and Peak of the Panic Attack. (From “The Psychophysiology of Relaxation Associated Panic Attacks” by A. S. Cohen, D. H. Barlow, and E. B. Blanchard, 1985, Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 94, p. 98. Copyright 1985 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. Reprinted by permission.)

Another fruitful approach to the causation of panic is the search for a straightforward misattribution of otherwise normal somatic events. Currently, there seems little question that cognitive processes have an important role to play in panic (Beck, 1988; Beck & Emery, 1985; Clark, 1988; Sanderson et al., 1989). But more sophisticated cognitive theorists such as Beck and Clark would not now advocate a linear causal model. Rather they would recognize and incorporate existing strong evidence for biological contributions to panic. This evidence includes but is not limited to studies demonstrating a strong familial aggregation of panic attacks (Crowe, Noyes, Pauls, & Slymen, 1983), as well as preliminary twin studies suggesting that panic (or at least some vulnerability to panic) is inherited (e.g., Torgersen, 1983).1 It is also possible that greater specification of seemingly labile neurotransmitter systems in panickers (e.g., Charney & Heninger, 1986; Nutt, 1986) or cerebral blood flow patterns associated with panic will enlighten us further on biological bases of panic, even if specific markers are not found (e.g., Reiman et al., 1986).

In any case, if the history of research in psychopathology is any guide, linear causal models will give way to multi-determined causal sequences. In the case of panic, the implication of such a systemic model is that both psychological and biological factors would contribute to causation interacting in the context of a feedback loop. A further implication of this model is that both psychological and pharmacological interventions could be effective for panic and that each intervention would affect both biological and psychological components of the panic cycle.

A model in construction at our Center attempts to integrate some of the biological and psychological data emanating from the study of panic and anxiety in the context of emotion theory. This model has implications for the nature of anxiety, which I consider first. Subsequently, I return to considering the nature of panic.

Anxiety

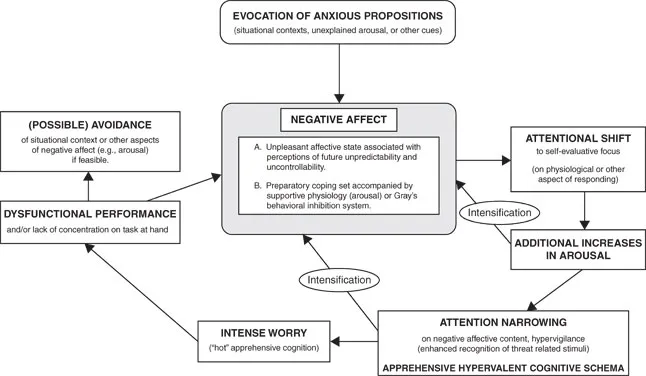

Most emotion theorists who speak to the issue have concluded that anxiety is a construct that clearly differs from related emotions such as anger and fear. Contrary to conclusions in general psychology textbooks, anxiety is not just fear without a cue. Rather, theorists as diverse as Carol Izard (1977; Izard & Blumberg, 1985), Richard Hallam (1985), Peter Lang (1979, 1984, 1985), and neurobiological theorists such as Robert Cloninger (1986) and Jeffrey Gray (1982, 1985) have concluded that anxiety is a blend of different emotions and cognitions or perhaps a diffuse affective network stored in memory that is very difficult to define. Based on data developed in our Center and elsewhere, I think that the evidence supports a conceptualization of anxiety as a loose cognitive-affective structure which is composed primarily of high negative affect, a sense of uncontrollability, and a shift in attention to a primarily self-focus or a state of self-preoccupation. The sense of uncontrollability is focused on future threat, danger, or other negative events. Thus, this negative affective state can be characterized roughly as a state of “helplessness” because of perceived inabilities to predict, control, or obtain desired results in certain upcoming situations or contexts. If one were to put anxiety into words, one might say, “That terrible event could happen again and I might not be able to deal with it, but I’ve got to be ready to try.” From this point of view, a better and more precise term for anxiety might be anxious apprehension. This conveys the notion that anxiety is a future-oriented mood state where one is ready or prepared to attempt to cope with upcoming negative events. This is best reflected in the state of chronic overarousal that seems to characterize anxiety and those who present with anxiety. This arousal may be the physiological substrate of “readiness” which may underlie an effort to counteract helplessness (e.g., Fridlund, Hatfield, Cottam, & Fowler, 1986). Vigilance (hypervigilance) is another characteristic of anxiety that suggest readiness and preparation to deal with negative events. The process of anxiety, as this model would have it, is presented in Figure 13.2.

With more specific reference to the model in Figure 13.2, a variety of cues, or propositions in Langian (1985) terms, would be sufficient to evoke anxious apprehension without the necessity of a conscious rational appraisal. The cues may be broad based or very narrow, as in the case of test anxiety or sexual dysfunction. The state of negative affect with its associated arousal and negative valance is, in turn, associated with distortions in information processing. These cognitive distortions are characterized by an attentional shift to a self-evaluative focus (or a rapidly shifting focus of attention from external sources to internal self-evaluative content). Evidence suggests that this, in turn, further increases arousal forming its own small positive-feedback loop with negative affect.

Figure 13.2 The Process of Anxious Apprehension. From Anxiety and Its Disorders: The Nature and Treatment of Anxiety and Panic (p. 250) by D. H. Barlow, 1988, New York: Guilford. Copyright 1988 by Guilford Press. Reprinted by permission.

Continuing on in the larger feedback loop, attention narrows on to sources of threat or danger, setting the stage for additional distortions in the processing of information, and one becomes hypervigilant for cues or stimuli associated with sources of apprehension (e.g., MacLeod, Mathews, & Tata, 1986). This process results in arousal-driven worry that, at intense levels, is very difficult to control by clients (Borkovec, Shadick, & Hopkins, in press).

At sufficient intensity, this process results in disruption of concentration and performance and, ultimately, avoidance of sources of apprehension if this method of coping is available. Arousal-driven anxious apprehension will, of course, only interfere with performance if some performance is required. In situations where performance may not be called for immediately, but where perceptions of loss of control or other negative affective content have become associated with a number of important life events (e.g., health, finances, and family concerns), the process of worry will emerge. The intensity of worry will increase or decrease depending on situational context, the amount of underlying autonomic arousal that is available at the time for transfer (Zillmann, 1983), and/or the presence of other “propositions” capable of calling forth this diffuse cognitive-affective structure.

Evidence for each of these components of anxiety and their connection is presented in some detail elsewhere (Barlow, 1988). It is also important to note that this is not a description of the etiology of anxiety but rather an illustration of the process of anxious apprehension. The etiology of anxious apprehension and a description of the biological and psychological vulnerabilities that predispose this state follows later and is fully discussed elsewhere (Barlow, 1988).

What is the purpose of anxiety? Why are we programmed to become anxious? This has prompted much speculation from philosophers and psychologists but also generated some data. We have known for over 80 years that organisms become more vigilant, learn more quickly, and perform better both motorically and intellectually if anxious (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908). We also know that both benzodiazepines and relaxation interfere with effective performance (Barlow, 1988). From this point of view, anxiety can be very adaptive, up to a point, and the adaptive purpose of anxiety would seem to be planning and preparation to meet a challenge or threat. As Liddell (1949) noted,

The planning function of the nervous system, in the course of evolution, has culminated in the appearance of ideas, values, and pleasures—the unique manifestations of man’s social living. Man, alone, can plan for the distant future and can experience the retrospective pleasures of achievement. Man, alone, can be happy. But man, alone, can be worried and anxious. Sherrington once said that posture accompanies movement as a shadow. I have come to believe that anxiety accompanies intellectual activity as its shadow and that the more we know of the nature of anxiety, the more we will know of intellect. (p. 185)

It is also well-known that anxiety distributes as a trait (Eysenck, 1967, 1981) and is expressed more or less by most individuals under certain situations. Therefore, it is only very intense anxiety or perhaps anxiety with an inappropriate focus that comes to the attenti...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Permissions Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Nature, Diagnosis, and Etiology of Anxiety and Related Disorders

- The Ascendance of Evidence-Based Psychological Treatments

- Index