![]()

1 Beginnings

Given the sustained attention to the size and shape of women’s bodies in the contemporary era, it is unsurprising that manipulation of the female physique has emerged as a crucial theme in art by and of women, as apparent in the recent exhibitions that have featured women’s art practices.1 Originating in 2007 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, California, “WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution” was broadly concerned with the way that the feminist movement has altered the art world, particularly in the way that artists increasingly used the female body and women’s narratives as the subject of their art. As the exhibition showed, feminist attention to body art and performance generally has proven fertile ground for engagement with body image.2 I was lucky enough to see the show at MoMA PS1 in 2008 and was immediately struck by the interactions of all these feminist masterworks.

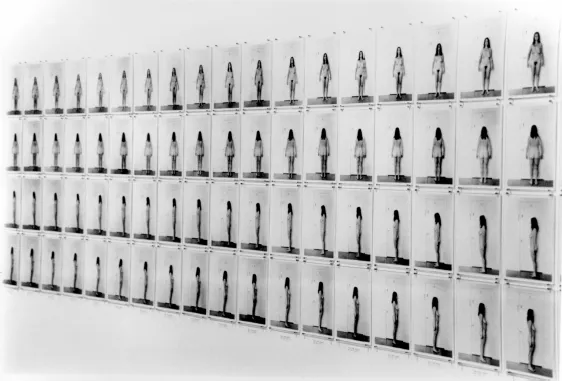

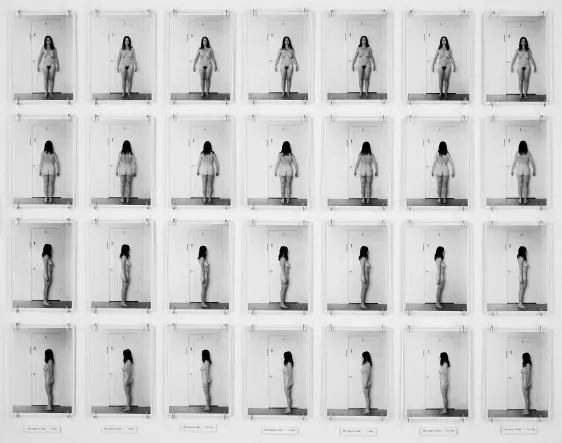

Meandering through the tiny rooms and pausing to watch the videos and study the works, I wound up in a narrow space, slightly larger than a hallway, that had only two pieces installed. On one side was a carpet, various consumable objects (like drinks and books), and photographs, and amid these items a recorded loop of Barbara T. Smith repeating “Feed me … Feed me …” played over and over. Feed Me (1973) was a work I was not familiar with, but I was intrigued. On the opposite wall was a piece I knew well: Eleanor Antin’s Carving: A Traditional Sculpture (1977, Figure 1.1 and 1.2), a photographic diary of a 10-pound weight loss over the course of thirty-seven days. As I stood, looking at Antin’s body over the course of a short time and trying to discern if you could actually see her documented weight loss, Smith’s “Feed me … Feed me …” was inescapable. Because of this installation, I saw Antin’s work in a new light. What Antin had presented as a conceptual exercise in sculpting her body, now seemed to resonate as a piece about the struggles of women in Western society forced to behave and look a certain way. At this moment, my project began, and I knew I had to investigate how a growing number of contemporary artists have worked specifically with female body image as a subject for their art. Because the preoccupation with weight is preeminently visual, artistic interventions can be particularly powerful as a way to address societal expectations. I examine significant examples of such projects by multiple artists, locating their works within a larger social and historical context as well as within recent feminist discourses on the body.

The artists to be discussed have made work that has been fundamentally shaped by the increased societal awareness of body size and the imperative for weight loss that might be dated from the 1960s, signaled by the founding of Overeaters Anonymous in 1960 and Weight Watchers in 1963; the rise of popular low-calorie food products, beginning in 1962; and the discovery of the importance of exercise to weight loss, evidenced by the first publication of a chart measuring calories burned during certain workouts, in 1965. Together, such developments in the United States came to affect how women have viewed their bodies since the 1960s.3 The problematic prioritizing of thin female bodies dominates Western culture from the 1960s forward. Gradually, these ideas will spread to Europe and the rest of the world, but it often still comes back to the United States, who presently has a strong and dominant reach in cultural developments. Unsurprisingly, with the increasing societal privileging of the thin body came a corresponding increase in instances of fat phobia and size discrimination.

Figure 1.1 Eleanor Antin, Carving: A Traditional Sculpture, 1972, Installation View, 148 silver gelatin prints and text, 7 × 5 inches each

These issues were further complicated by the fact that the United States Food and Drug Administration approved the birth control pill as a contraceptive in 1960, in one of the most important social advancements of the twentieth century. By the end of 1961, 408,000 American women were taking the pill, and just two years later, the number had jumped to 2.3 million.4 Early versions of the pill contained high amounts of estrogen, resulting in headaches, weight gain, and other negative side effects. In addition to changing women’s bodies and providing control over family planning, the birth control pill was also crucial to the development of the sexual revolution as well as the women’s liberation movement.

Significantly, the women’s liberation movement moved into mainstream consciousness with the protest staged by Robin Morgan and the New York Radical Women (NYRW) at the Miss America Pageant in September 1968.5 It is worth emphasizing that one of the first gambits women used to try to dramatize their oppression in the 1960s was centered on society’s evaluation of women’s bodies based on appearance. Speaking out against the oppression of women, which the NYRW saw as epitomized by the pageant, the protesters staged a series of events including picketing, guerrilla theater, and visits to individual contestants urging them to quit the pageant. Perhaps the most significant part of the protest was the now-infamous “bra-burning” event. More than 100 women gathered, throwing bras, girdles, high heels, curlers, makeup, and Playboy magazines into a trash can. No bras actually were burned, however. Unable to secure the permits for a fire, the women instead threw the objects into a barrel, dubbed the Freedom Trash Can.6

Figure 1.2 Eleanor Antin, Carving: A Traditional Sculpture (detail), 1972, Installation View, 148 silver gelatin prints and text, 7 × 5 inches each

Morgan, one of the main organizers, sent a press release to major news outlets not only to encourage people to attend, but also to explain the reasons behind the protest. She wrote, “On September 7th in Atlantic City, the Annual Miss America Pageant will again crown ‘your ideal.’ ”7 Calling the contest “The Irrelevant Crown on the Throne of Mediocrity,” Morgan further wrote,

Miss America represents what women are supposed to be: inoffensive, bland, apolitical. If you are tall, short, over or under what weight The Man prescribes you should be, forget it. Personality, articulateness, intelligence, and commitment—unwise. Conformity is the key to the crown—and, by extension, to success in our society.8

Pointing out that most women would never even be considered for the title of Miss America because of their race and body size, the NYRW blamed the pageant and, by extension, the media and their coverage of the contest, for putting pressure on women to look a certain way. By throwing out bras and girdles, the women made clear they did not want to bind and alter their bodies to make them conform to a given ideal. After Miss Illinois had been crowned Miss America during the ceremony, two protesters unfurled a large banner over a balcony that proclaimed “Women’s Liberation”; this was one of the first times that many across the country had ever heard the term.

The women’s liberation movement, as well as the closely affiliated women’s rights movement, developed in the 1960s under a wide variety of leaders, strategies, and organizations.9 There was not one issue that united the movement; rather, a plethora of issues engaged women on a number of different levels. Susan Welch compared the choice of issues to a “cafeteria”: “Women can support the movement for a variety of reasons including economic self-interest, promotion of self-esteem, or strictly social and companionship needs.”10 But within this multiplicity of ideas and concerns, women generally spoke out to defend equal rights. Further, this ability to join organizations and groups with shared values provided women with an important support system. For example, the National Organization for Women, founded by Betty Friedan, as well as Ms. magazine, founded by Gloria Steinem, created new opportunities for women to share their experiences and connect with one another. Magazines, television, books, and all types of media began to present outlets where women could, in the parlance of the time, “find themselves.”11

Art, then, was no different: as more women found their voice in the 1960s and 1970s, they were using their lives and their experiences in their artwork. This is particularly evident in performance art, a relatively new mode of expression wherein men had not yet established their dominance in the medium, allowing women more latitude in using and shaping performance practices. Meiling Cheng observes,

Performance also offered the collective environment sorely needed for many women artists, most of whom suffered from isolation, lack of self-esteem, and doubts about their desires to practice art. Live performance helped these women process the information gathered from consciousness-raising meetings.12

Performance art became a way that women could engage in a discussion of their bodies on their own terms, as art historian Jeanie Forte further articulates:

Women’s performance art has particular disruptive potential because it poses an actual woman as a speaking subject, throwing that position into process, into doubt, opposing the traditional conception of the single, unified (male) subject. The female body as subject clashes in dissonance with its patriarchal text, challenging the very fabric of representation by refusing that text and posing new, multiple texts grounded in real women’s experience and sexuality.13

Using their bodies in performance resulted in works that could reflect an autobiographical, therefore personal, presence, but could also challenge larger societal issues concerning the treatment of women and society’s perception of women’s bodies and behavior. Performance art led the way to other artistic developments to incorporate women’s concerns. After the protests and consciousness-raising of the 1960s, by the 1970s, many of the female artists began incorporating these ideas into their work, so it should not be a surprise that issues regarding female body image became viable subjects.

Through a discussion of four important, transitional artworks, the ways artists began to challenge the ideal female form become evident. Adrian Piper’s Food for the Spirit (1971), Barbara T. Smith’s Feed Me (1973), Eleanor Antin’s Carving: A Traditional Sculpture (1974), and Martha Rosler’s Losing: A Conversation With the Parents (1977) each present important viewpoints on the way women’s physique and size is constantly being negotiated and debated. Yet in the early adoption of these subject matters, these four artists maintain other, often more prioritized, interests. It is as if the focus cannot yet be on female body image alone because it is a secondary concern as other issues dominate discussions of these artworks. Nonetheless, these works lay the groundwork for the rest of the artists in this book. Although not fully committed to larger feminist issues concerning body size, each of these four artists expands the visibility and the viability of this topic as a subject matter in the visual arts.

Adrian Piper (b. 1948), like many early feminist and performance artists, utilized her body in her artwork, which was informed and inspired by conceptual artist Sol LeWitt. In 1971, after she had graduated from the School of Visual Arts in New York and was working on a Bachelor of Arts in philosophy at City College of New York, Piper spent the summer reading and reflecting on Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (1781). For this project, she set guidelines for herself; she stayed in her apartment and focused on Kant, leaving only for short trips to the grocery store and walks for exercise. Furthermore, she spent the months fasting and practicing yoga with the hopes that she would thus be able to more fully understand and comprehend Kant’s work. While she conceived ...