![]()

Part I

General Aspects

![]()

Chapter 1

Setting the Frame

Marginality as a permanent issue

In a paper, published just before the major turnaround of the European political map, Brücher (1989) asks the question if the Saar-Lor-Lux transborder region covering the Saar Bundesland (Germany), the Lorraine Region (France) and the small state of Luxemburg was a border region, a periphery or the core area of the European Community. The title of his paper points to one of the central problems in discussing marginal regions: the issue of (spatial) scale. It will accompany us throughout this book, it is always present and will be illustrated in the case studies presented. Brücher himself cannot answer the question he asks. Looking at its location within the European Union, the Saar-Lor-Lux region is doubtlessly central. From an economic and traditional resource perspective (coal and iron ore, steelmaking), on the other hand, it is rather marginal. Similarly, the politico-administrative heterogeneity of the three countries involved constitutes a significant drawback. However, the existence of peaceful and intensive transborder contacts since World War II speaks in favour of centrality.

A second major point in this discussion, the role of time, is illustrated by Reitel (1989) in his paper on the transformation of mining (iron ore and coal) and the steel industry in the same region: once the most important economic factor, they have become minor activities within the period of half a century and have by now almost completely disappeared. His paper emphasizes the dynamics of regions that depend on internal and external factors and reminds us of the question of (temporal) scale: processes are both short-term oscillations and long-term cycles.

Marginality in space and time – the two essential dimensions for geographic research – is the topic of this study. The fundamental concept will be discussed both theoretically and in connection with specific domains in Chapter 2 and, more in depth, in Part II. Most frequently, geographers have investigated economic marginality, looking at regional disparities and disadvantaged regions. More recently, social and cultural aspects have been studied; in this field, geographers cooperate with sociologists, social anthropologists and ethnologists in a multidisciplinary way. The political realm has so far been treated very little, probably because politics is an issue that dominates both economy and social life to a considerable extent. To these traditional domains in the social sciences we shall add the environment (our physical living space). The perspective in this case will be somewhat different. The environment is central to human existence, but all too often has it been marginalized in our decisions to allow for greater economic profit. Marginality in this case emphasizes the way humanity looks at it, perceives it, and has been dealing with it over time. It would be wrong to simply discount it; any geographic approach has to take both man and nature into account (see Chapters 4 and 7). Humans have to live with the environment, they modify it according to their ideas, but they are also part of it, they also have their own nature. Man has created a considerable range of answers to the challenges of the environment, and this variety persists until today: 'So there is a physical or ecological envelope, but within this, human technology and knowledge allow a variety of adjustments to the resources of the planet.' (Simmons, 1989, p.6). The significance of culture as the background to our actions becomes apparent.

The latter statement takes us to a third important point: the study of marginal regions and marginality is not simply 'objective' research but is related to human perception. The phrase 'marginality is a state of mind' may sound simplistic (after all, there are 'objective' criteria for measuring marginality and delimiting marginal regions), but it does hold some truth. A newspaper article published a few years ago in a regional Swiss paper furnishes a telling example. Its title 'Innovations: Switzerland runs the risk of being marginalized' expressed the fear that in the field of technological innovation, Switzerland risked to lose its position at the forefront (La Liberte 09.09.1999). To the readers of the paper, this article sounded the alarm bell (it did so for this author), but when reading the text carefully, they understood that reference was made to innovation within Switzerland only, not to innovation achieved by Swiss firms abroad. This puts the article into a different perspective: we may safely assume that information on innovations will be circulated inside the firms and in this way flow back to headquarters and plants in Switzerland. Marginality, in this case, was clearly an invention of the journalist who gave his own interpretation of a report of the Swiss Council for Science. While pointing to potential problems in Research and Development within the country, it also highlighted positive elements for Switzerland: the general framework for research and development (R&D), the massive investment of 9.9 billion Swiss francs in R&D (67 per cent by private enterprises, 27 per cent by public funds), to say nothing of the favourable political and human resources situation were quoted as important trump-cards for the country. The title of the newspaper article conveyed a pessimistic message only, missing out on the positive aspects. The question remains open if the journalist intended to set a political signal towards the promotion of research in general and universities in particular, or whether his was a purely local perspective given the need for funds in scientific research.

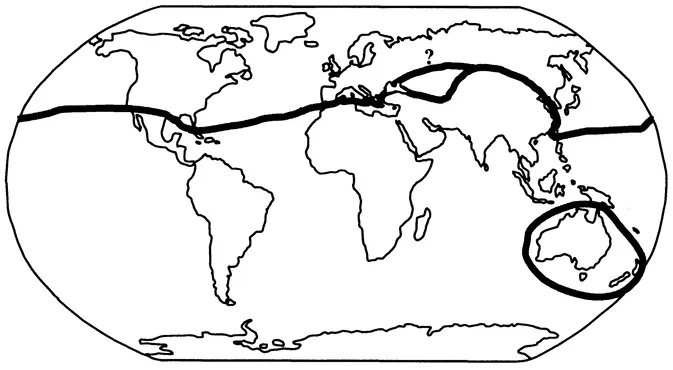

The examples mentioned above may look insufficient to our cause. Let us therefore add another spatial dimension. The late 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed an increasing rift between a 'central' and a 'marginal' world, between the rich and powerful North and the poor and weak South, a new limes between the 'Empire' and the 'New Barbarians' (Rufin, 1991, see Figure 1.1). The marginal world is that part of the globe that experiences most political unrest and civil wars, and that as a consequence receives most refugees in innumerable temporary camps, the 'archipelago of misery' as Rufin calls them (ibid., pp.64 ff.; see below, p. 166 f. and Figure 6.2), that risk to become the home of many for an unknown length of time. These camps (or gulags) are marginal regions within marginalized countries that belong to the marginal world – a perfect illustration of the babushka principle (the Russian puppets where a smaller puppet is inserted in a bigger one).

Figure 1.1 The global North-South divide Source: Rufin, 1991, p. 147 (modified)

It is cynic to pretend that marginality has always been part of history and will have to continue like that into the future. To think in this way means to deprive people of all hope to step out of a hopeless situation. It is imperative to fight marginality even if we know that we cannot eradicate it. We must do our best to eliminate its negative impact on the people and the environment.

To do justice to the topic, the temporal dimension has to be recalled as well. The political situation in the Middle East offers a good example. Depending on circumstances and power perspectives, centrality and marginality are interchangeable at will. In their regional geopolitical calculations, the US had attributed to Iraq a strategic position and supported the coup of 1963 that eventually brought Saddam Hussein into power (1979). From the 1960s onwards, they supplied the country with money, arms, and technology. 'So enduring was America's ardour, or rather its gratitude to Iraq for protecting its client Arab states from Iran's revolutionary virus, that Saddam was given everything he wanted, almost up to the day he invaded Kuwait in August 1990.' (Pilger, 2002, p.66). Suddenly, after the invasion, the image of this same person was reversed, and Saddam Hussein became a sort of public enemy number one, who had to be ousted from Kuweit. His fault was that he had tried to become independent of the great benefactor, but the Americans 'want another Saddam Hussein, rather like the one they had before 1991, who did as he was told.' (ibid., p.81). Central to the entire issue is not the country or who runs it but the chief energy source, oil. The regime as such does not matter.

These introductory remarks demonstrate that the theme of marginality is always present and will remain on the agenda in the future. It will persist on all possible spatial scales, and it may in certain cases be temporary, in others almost permanent. In our time, however, it has to be seen before the background of two important processes underway, globalization and deregulation. Indeed, marginalization can be seen as a consequence (maybe the major one) of both of them. For this reason, it is necessary to briefly discuss them and look at the foundation they lay for marginalization. Let it be made clear, however, that marginality is not the result of globalization and deregulation; the two processes have simply reinforced what is as old as human history.

Aspects of globalization

Globalization has become a fashion word in our time, used indiscriminately by everyone to describe almost anything that looks negative or seems to have a negative impact on our life – it is often pronounced almost as a swearword. The popular interpretation of the word, however, does not take the complex reality into account that merits serious reflection. Being vague, the term leaves a number of issues open, but is certainly not simply negative.

Looking at it from a semantic perspective, the adjective 'global' has two meanings: on the one hand it refers to the entire world (the globe, meaning worldwide), on the other hand it is a synonym to inclusive or all-encompassing, both in the concrete and in the abstract sense. By its very essence, it is a static term. The verb 'to globalize' and the noun 'globalization', on the other hand, suggest movement, dynamics, not a steady state. The word-family is value-free. It is therefore astonishing to observe how globalization has been used in a very diffuse manner. On the one hand it is presented to the public as inescapable destiny, on the other it has been loaded with strongly negative connotations. This may lead to contradictions and confusion, as is the case of the anti-globalization movement, which is itself organized globally. The choice of name masks the real target of the opposition, which is in fact the unbounded market liberalism.

A closer look at the first meaning of 'global' imposes itself. The World is commonly understood as the Planet Earth, global therefore refers to just this one scale. This, however, is our modern understanding of the term, based on our daily practice of shopping in the supermarket and watching TV news. Through modern information, communication and transportation technology, the globe has shrunk and physical (as well as time) distance has lost much of its former significance (Baumann, 1998, p. 14 f.). However, the World is not an objective reality; it is perceived by humans from different perspectives and can be associated with the living or activity space of a particular group or society. 'Global' then comes to mean the totality of the known part of the planet at a moment in time (history), and it has held this meaning with the Romans, the Chinese, and the Arabs who traded and conquered lands within a certain range of their centres of power. The colonial empires eventually changed the scale of operation from 'regionally global' to 'truly global'. From this perspective, globalization is a very relative term that must not be reserved for the 20th and 21st centuries.

The history of globalization can be traced back to the early periods of human history, provided we accept to look at 'global' in relative terms and to take the slow speed of transportation and diffusion into account. The dissemination of cultural elements, the mixing of cultures, and the ensuing creation of new cultures or cultural elements are part of our heritage. No group or society could evolve in isolation, as a closed system; outside influences have always penetrated and exercised their influence. Elements that play a particularly strong role in a people's identity will even be appropriated to serve as the main feature of a people. 'How many Italians, for example, realize that pasta originates from China?' (Holton, 1998, p.28). Even this book is a witness to the complex historic globalization process, if we look at the language (English, as a mixture of Germanic and French elements), the writing (the alphabet developed in former Phoenicia), the numbers based on the Arabs 'who in turn learnt them from Indians, who had earlier invented positional notation.' (ibid.). Printing, finally, although now with a new technology, was invented in China (ibid.).

It would be unwise to condemn globalization as the evil of the 20th and 21st centuries. It is true that there are negative effects that have to be criticized and eliminated or corrected, but there are also positive ones, and they have to be cultivated. The domination of the entire world by one economic philosophy and the political interests behind is doubtlessly harmful to the cultural and natural diversity on earth. The fact that Human Rights' violations can be denounced on a worldwide scale within almost real time, that we have become aware of global problems that transcend our daily ones, or even the possibility to enjoy theatre, music and sports events wherever they occur is a positive side of the globalization process – this is a means to strengthen solidarity among the inhabitants of the globe.

In order to clarify what we are talking about, it is important to approach the globalization debate with a solid conceptual basis. The German sociologist Ulrich Beck (2000) distinguishes between the dynamic and the static semantic fields and has coined respective terms with precise contents: 'By globalism I mean the view that the world market eliminates or supplants political action – that is, the ideology of rule by the world market, the ideology of neoliberalism.' (Beck 2000, p.9). Anti-globalists therefore fight globalism in the shape of the neoliberalist credo. 'Globality means that we have been living for a long time in a world society, in the sense that the notion of closed spaces has become illusory. No country or group can shut itself off from others.' (p. 11; emphasis in the original). This is not new, as Adamo's statement about the Great Depression of the 1930s illustrates: 'The crisis of 1929 has demonstrated a) that the earth is no longer just an ecosystem but is to a large part contained in one single socio-system; b) that the dominant economy in the system earth is no longer Great Britain but the United States of America.' (Adamo, 2001, p.596; transl. WL). Nowadays, everybody on the entire planet takes part in this reality as soon as he/she watches television, listens to the radio, surfs on the Internet - or is affected by the war on terrorism or some sort of environmental pollution. Participation varies in space and time. 'Globalization, on the other hand, denotes the processes through which sovereign national states are criss-crossed and undermined by transnational actors with varying prospects of power, orientations, identities and networks.' (p. 11). Such transborder processes have been part of human history, intensified, however, from the 16th century onwards, when the European colonial powers sailed the oceans and annexed lands around the globe. From our European perspective, the great voyages of discovery constituted a new step in the ongoing process of globalization, a process that before had been limited to overland trade between Europe and Asia (the Silk Route). The discoveries, the colonization (appropriation), and the exploitation of foreign lands overseas constituted a fundamental break in globalization: the size and speed of the enterprise grew considerably, and the European influence went beyond exploiting natural and human resources and touched the social systems. This is where proto-globalization ended and the old globality system (the colonial system) came into existence.

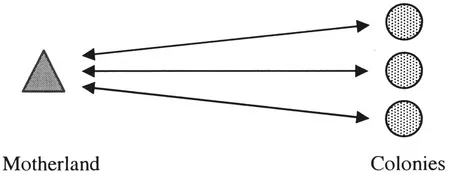

What we term 'old globality system' has been characterized by a functional construction (Adamo, 2001, p.594), based on the linear interdependence between motherland and colonies (Figure 1.2). Every colony exported its specific resources to and imported manufactured products from the motherland. This system was very static and conceived on a long-term basis, and the flows of goods were always the same. This system was not contested, because it brought wealth and power to Europe. The gradual technological improvements following the Industrial Revolution increased the speed at which it worked (the construction of steamboats) and facilitated the penetration of the colonies (the building of railways) and the communication within the system (telegraph and telephone).

Figure 1.2 The old globality system

The old globality system broke down definitely with decolonization but signs of a change had been visible before. The globalization process, on the other hand, simply took a new turn. When the United States (a former colony) entered the world market with wheat in the 1880s, they triggered off a major crisis in European agriculture. Their advent as a global player demonstrated that the old, bilaterally constructed globality system was defunct. They were no longer part of it, and t...