eBook - ePub

Streets of Splendor

Shopping Culture and Spaces in a European Capital City (Brussels, 1830-1914)

- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Streets of Splendor

Shopping Culture and Spaces in a European Capital City (Brussels, 1830-1914)

About this book

This book addresses the unresolved question of how urban retailing and consumption changed during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It replaces the usual focus on just one (type of) shopping institution with that of the urban shopping landscape in its entirety. Based on secondary sources for comparable cities and an in-depth empirical analysis of primary sources for Brussels, the author demonstrates that the unbridled commercialisation of cities in the nineteenth century cannot be understood without taking into account the entirety of the shopping landscape. Through a quantitative and qualitative analysis, she shows how and why the culture and spaces of shopping evolved.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Streets of Splendor by Anneleen Arnout in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Bursting blossoms

Brussels shops and shopping, 1830s

Late bloom

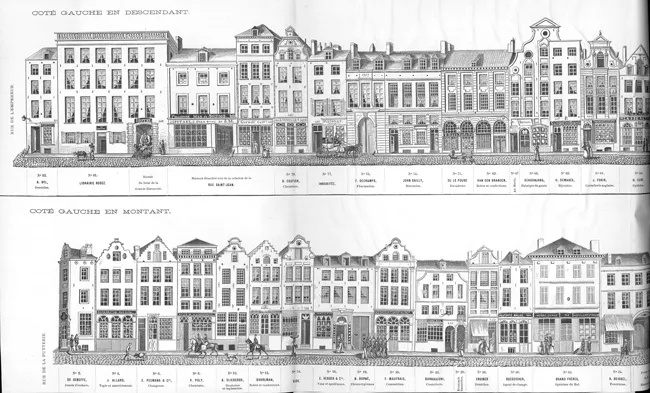

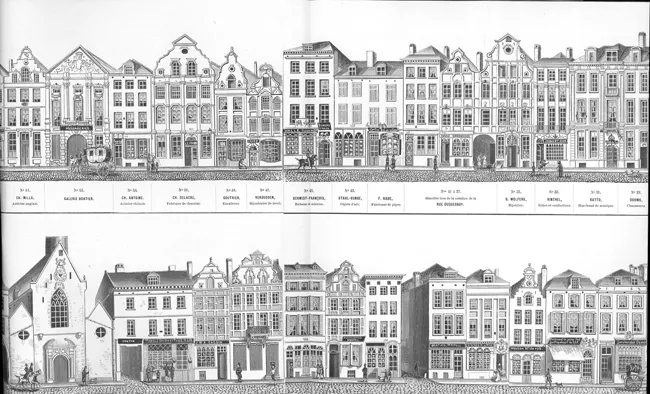

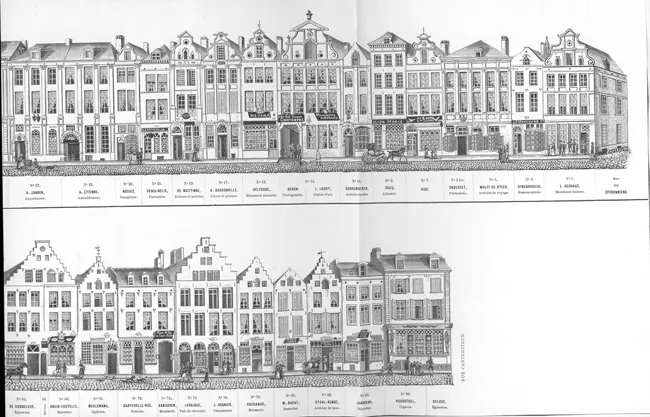

In his Bruxelles à travers les ages (1884), Louis Hymans published an engraving of the Rue de la Madeleine as it supposedly looked in 1825 (see Figures 1.1 to 1.3). What we see is a cobbled street, lined with sidewalks. Carriages, equestrians and soldiers make their way up or down the thoroughfare. There are several peddlers, some with carts and dogs. Dotted along the cobblestones and pavements are men, women and children in different configurations. Some of them are on the move, passing doors that provide entry to narrow step-gabled houses and modern neoclassical buildings. On the ground floors, shiny shop windows abound. Some take the shape of arched windows, while others are rectangular. Most are flat, but some are projected or have bow windows. All of them are made up of multiple windowpanes, varying in size in the different shops. Most shop signs are rectangular with the name of the shopkeeper and his trade written down, except for one that is shaped like a pair of glasses.1

The Rue de la Madeleine was the most fashionable shopping street of all Brussels. Several sources indicate that the engraving was intended to provide a faithful representation of the street. It provided the local shopkeepers with a commercial tool, showing customers the location and appearance of their stores.2 According to studies of eighteenth-century Brussels, the abundance of shop windows represented in this engraving was quite novel. The street had been filled with (fancy) boutiques for decades, but dedicated shop windows had been rare. Shop windows were of the same shape and form as windows in residential properties. Sometimes the door was ornamented and, in those cases, it was the only architectural marker of the property’s commercial function.3

All this changed in the early nineteenth century, when homeowners applied for permits to transform the façades of their eighteenth-century buildings. The files contain both the planned and existing state, the latter of which confirms that most early nineteenth-century shops had plain windows, separated from each other and the door by wide sections of plastered brick. The desired transformations aimed at installing a proper shop window by removing those separations and increasing the glass surface.4 Large, plate glass, shop windows (vitrines) soon became the norm. When the Quartier de la Monnaie was redeveloped in 1820–1821 the fronts planned for the new buildings did not specify the design of the ground floor, because it was assumed that tenants would want to design their own shop windows.5 The desire to achieve a completely symmetric design was made secondary to the commercial importance of the individualized shop window.

Figure 1.1 The Rue de la Madeleine in 1825 (drawn in 1884) – Part 1

Source: GUL, BRKZ.TOPO.885.F.03: Creative Commons License

Figure 1.2 The Rue de la Madeleine in 1825 (drawn in 1884) – Part 2

Source: GUL, BRKZ.TOPO.885.F.03: Creative Commons License

Figure 1.3 The Rue de la Madeleine in 1825 (drawn in 1884) – Part 3

Source: GUL, BRKZ.TOPO.885.F.03: Creative Commons License

In terms of shop windows, Brussels was unfashionably late to the party compared to larger European cities.6 In the shopping streets of London, for example, shop signs, fascia boards and projecting or bow windows had marked the presence of shops from the early eighteenth century onwards. When large shop windows became the norm among fashionable shopkeepers, it became unfashionable to drape, hang and pile up goods around windows and doors, on the window sills and in front of stores. Displaying goods on the streets became increasingly associated with the lowly trade of market and street vendors.7 In historiography, the advent of the shop window has been considered constitutive of a burgeoning culture of leisurely shopping.8 British, French and Dutch historians have argued that shopping became a sociable pursuit among moneyed middle classes during the nineteenth century. It became something that transcended the mere exchange of money for goods: a social activity pinned on civilized contact between shopkeeper and client, interaction between peers, gathering information on fashion trends, and pleasurable walking.9 Crucial to this development were a significant growth in the number of shops, a denser clustering of a specific type of shops in the city center, the refashioning and redevelopment of the central streets, and changing retail practices.10

Whether the absence of shop windows indicated an underdeveloped shopping culture is unclear. Some argue that window-shopping did not exist before 1800 because there were no shop windows.11 Sure enough, there are elements that suggest such a late bloom in Brussels. While there were many shops, shopping streets did not have the clear profile they had in Amsterdam, most British cities and even in Antwerp. Central shopping streets held a variety of shops and not all of them were conducive to the type of shopping that was centered on fashion and luxury and the comparison of goods.12 The urban infrastructure did not help either. Like in Paris, but unlike London and Amsterdam, the city’s street plan was a maze of tortuous streets remarkably reminiscent of a medieval city.13 Streets lacked comfortable sidewalks and proper lighting. Without sidewalks, pedestrians had to keep an eye out for oncoming vehicles, carts and pedestrians, while also avoiding trapdoors, market and other displays, not to mention rain and mud puddles. This situation must have become even more problematic in the early nineteenth century – a period of most intensive demographic growth.14 Significantly, the sprawl of shop windows in Brussels at the turn of the century coincided with the construction of the city’s first pavements. Established out of concern for traffic flow, these sidewalks were first installed in central streets. Their construction coincided with the first wave of building applications for shop windows. In fact, both were constitutive of each other. The building code stipulated that shopkeepers who wanted permission to transform their shop fronts were obliged to construct a sidewalk too. Conversely, sidewalks helped to facilitate window-shopping and might have attracted more people strolling, which in turn could prompt shopkeepers to pimp their façades.15

Shop windows were obviously not the only way to seduce potential customers on the street. Clé Lesger has shown how shopkeepers in Amsterdam would display their wares on or in front of their façades.16 Down-market London shopkeepers enticed their eighteenth-century customers in similar ways.17 There was also the possibility of elegant displays behind ordinary windows, or that customers might have travelled to the Rue de la Madeleine in carriages, walking in and out of the shops and inspecting indoor counters much like they would stroll the streets looking at windows in London. Wolfgang Schivelbusch has argued that exclusive eighteenth-century boutiques invested in a luxurious interior that was reminiscent of ostentatious drawing rooms to please their equally ostentatious customers. He argued that the shift to windows was part of a democratization of the clientele.18 Perhaps shopping remained reserved for the extravagant just a little while longer in Brussels?

International research has furthermore shown that customers felt free to browse in shops long before the introduction of self-service.19 Entering a shop and asking to see the goods did not come with an (implicit) obligation to buy. Therefore, what centered on the window in contemporary London might have centered on the interior of the store in Brussels. While the increasing population presumably made it more challenging, moneyed customers had always been accustomed to navigating busy streets without sidewalks. Did the lack of sidewalks – which the majority of Bruxellois had yet to become acquainted with – really keep them from walking from store to store? In short, there is little evidence to support the idea that men and women did not engage in the multilayered social activity of visiting shops, browsing and informing themselves of the latest fashions in interactin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of maps

- List of tables and graph

- Acknowledgments

- List of abbreviations

- Setting up shop: Introduction

- 1 Bursting blossoms: Brussels shops and shopping, 1830s

- 2 Shopping in style: The Galeries Saint-Hubert and the Chaussée

- 3 Cleaning house: Markets and halls

- 4 Bigger and brighter: Downtown and the department store

- 5 Shopping galore: Brussels shops and shopping, 1910s

- Closing time: Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- Index