![]()

1

Introduction

In a tiny church in a Cretan ravine once serviced by Orthodox monks, in a family chapel in Macedonia inconspicuous among fields of grain, I felt the religious mystique that I sometimes experienced in New Mexico. There also such oratories preserved the kind of primal Christianity seldom apparent in sumptuous modern churches, neon-lit and resounding with electric-driven organ music.1

The discovery of parallel worlds and experiences within the Christian universe is a function of the observer’s knowledge and sensibility but also of the actual forms that objects, structures, and practices take when informed by an encompassing imaginary. An exploration of Christian iconography across chronological and geographical divides inevitably encounters tradition. On the surface, tradition appears to function as a stultifying force that carves a repetitive and rigid path in the midst of a fluid, polymorphous, and ever-diversifying image-world. In reality, creative tensions between continuity and disruption, uniformity and variety define rather than undermine tradition. Their exploration in this study begins with a comparison of Greek and New Mexican iconography.

Pál Kelemen’s (1894–1993) encounters with Greek and New Mexican Christianity were accompanied by a desire—Romantic and Modernist—for simplicity and authenticity that was premised on loss and recollection and presupposed a historically problematized consciousness. Tradition was approached in this context as the domain of insular and stagnant forms—a kind of visual archive or museum—that supplies the iconographer with images that will automatically resonate with his existential, imaginational, and spiritual needs. Working in a hostile, heterodox environment (Ottomans and Plains Indians respectively), Greek and New Mexican artists “clung to the fixed tradition that kept their hope alive… for them, studied perspective, three dimensionality, coloristic bravura, freedom of movement and of drapery held little interest.”2

Here, post-Byzantine icons and the painted and carved images of Spanish Catholic saints, known as santos and bultos respectively, seem to proceed (or emanate) from the same archetypal forms that obfuscate their geographic and cultural peculiarities. Thomas J. Steele (1933–2010) saw them in a similar light, as replicas of iconographic types that are sanctified in tradition—reflecting “a folk Platonic mentality.”3 In this approach, tradition consists of images that cannot stand solidly on their own ground—and in their own time—but point always to the past or are seen as parts of an integral geography that reaches back to Christianity’s archaic and pristine origins—an idea celebrated by the New Mexican artist, historian, and poet Fray Angelico Chavez (e.g., New Mexico as another Castille and Palestine).4 This geography does indeed exist, but it is comprised of multidirectional trajectories, as we shall see.

On the Greek side, the romance with the post-Byzantine and Greek icon and tradition is best exemplified in the work of Fotis Kontoglou (1895–1965). Kontoglou sought to revive an Orthodox aesthetic as an antidote to Nazarene and modernist influences on nineteenth- and twentieth-century Greek iconography. His view of tradition will be examined in detail in chapter 12. Contemporary scholarship uses the term as an art historical category without exploring its aesthetic and theological underpinnings. Iliana Zarra has written the most comprehensive study to date of religious art produced in Thessaloniki in the nineteenth century under Ottoman rule (prior to the city’s liberation in 1912), which points to the confluence in a wide range of works of regional, Western, and eclectic trends.5

Zarra identifies elements that suggest transcultural realities and creative tensions with tradition. Expressive of a cosmopolitan vernacular, these images reflect the rise of an urban, modernizing aesthetic. She writes of a dynamic environment in which the “survival of the near past is enriched, adjusted, and formatively engaged in new attitudes” to religious painting.6 Maria Vassilaki’s important volume on post-Byzantine icons from the Averof Collection notes patterns of syncretism, eclecticism, and adherence to tradition in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century devotional icons from the Heptanese, Epirus, and northern Greece (the last two part of the Ottoman Empire in this period), suggesting similar tendencies with the Thessaloniki scene.7 The work of Zarra and Vasilaki makes it clear that icons cannot be fixed in a given aesthetic, technological, and cultural orientation but instead need to be approached from multiple perspectives and considered as ontologically versatile and yet resilient objects.

Recent literature on santos is pluralistic and eager to explore the ways in which they deviate from their European origins and Christian imaginary and reflect the ideological, cultural, and spiritual vicissitudes of Spanish colonization across time.8 Despite its significant contributions to the study of New Mexican iconography, this approach is limited by its neglect of the theological dimensions of these images and the ontological and imaginational realities they engender in that context. Like icons, santos have a history, a genealogy, and a life in Christian iconography. Transcultural modalities and transformations are an inevitable part of this life. Iconographic types become naturalized in new localities and geographies that add new dimensions and meanings to the works. From our perspective, the importance of non-Christian meanings that arise in this context lies less in their disruptive or subversive effect and more in the transcendental dimensions that they engender in the art object. To the extent that these dimensions form within the image, they remain Christian and work in analogical ways that duplicate them in other theologies and ritual worlds and impart on the aesthetic object plasticity and liminality.

The same applies to the ideological aspects of Spanish colonialism and their expression in religious art. The collusion of political and religious authorities in the colonization of New Spain does not automatically translate into an aesthetic paradigm that is replicated in all works. That images functioned instrumentally in these contexts is certain but that they did so exclusively is not. There were mechanisms of disengagement from what we might call propaganda, and these had to do with the fact that present in many of these images were transcendentalized beings (Christ, the Virgin, angels, saints) that were involved in redemptive and salvific acts, in eschatologically charged settings.

Being in that sense liminal, they could not be contained within the doctrinal parameters set for them and deliver the specific content needed for proselytization. Even when that content was incontestably there, ambiguity and poetization, as we shall see, were also present. This did not only affect instances of subversion or indigenous intrusion into the Christian imaginary. It also coincided with the spontaneous emergence of new imaginational realities that plasticized the art object and released it from its designated identity or purpose. It is thus important to keep the semiotic operations that might be detected in this kind of image open rather than assign them automatically to dominant forms of cultural and ideological construction derived from its immediate environment—or to those adopted by the dominated (colonized) imaginary.9

By the same token, clear, linear connections to other images that aim to elucidate a work’s meaning must take into account the refractions and fragmentations that characterize visuality in these liminal settings—miracles, apparitions, etc. This openness, however, should not be seen as unconditional but rather as the expression of the radical integrity of the art object. When an image is constantly subjected to the deconstruction of the “mental habits” that inform it, as in the widely influential work of Serge Gruzinski, this integrity is undermined.10 The reconstitution of the art object as perspectives shift and reveal their partiality, defers meaning to the deconstructing subjectivity (the cultural historian, theorist, etc.) and displaces the art object as the epicenter of activity. To be sure, the unveiling of an elusive or “chaotic” reality through this kind of analysis is welcome, since it subverts the constructs of a reified rationality. But it should not happen at the expense of the art object’s imaginal being and integrity.11 The equally legitimate claim that this being makes to meaning must be given its due.

Just like a subject is never a singular occurrence but always posits and transcends the subject-worlds in which its subjectivity is configured, so too an image is not a solitary being but always posits and transcends the image-worlds that inform it. These consist of other images with which it resonates or to which it can be referred not only in an originary, genealogical way (in the sense of lineage) but also in all kinds of lateral movements and dispersed trajectories. These image-worlds may find their analogs in the imaginational space where, as Cornelius Castoriadis (1922–1997) wrote, an “incessant flux” of figures and presentations at once underlies and defies normative perception (the institutor of the spectacle, the “stabilized” image)—a flux that in his view constitutes the subject.12

We shall tie this multilateral view of the image to the word eikon and the implicit in it and theologically mediated sense of self-actualization. This takes an image out of the exclusive domain of the subject and into a world of its own kind. This externalizing, objectifying dynamic is implicit in the verb eikonizein and in the concept of iconicity that we shall define in the next chapter. To this intricate image-world corresponds a participating or synergical rather than inspectional subjectivity. While the former joins its object in a mutual poetization and ambiguation, the latter constitutes the image as a simulacrum or as the dead (finished) transmission of a locution to be revived by an act of interpretation or decoded by a lucid, epistemic consciousness.

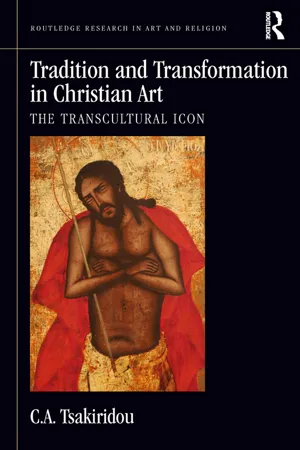

This study thus embraces the conceptual and methodological pluralism proposed by Gruzinski, Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Michel Espagne, Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, Monica Juneja, and Julie F. Codell, and benefits from the transcultural qualities that Claire Farago, Robin Farwell Gavin, Donna Pierce, and others have identified in the Christian art of New Mexico.13 It is inspired by points of aesthetic and theological convergence in some Greek and New Mexican images of Christ’s Passion. These suggest associations with connected empires and traditions (Byzantine, Latin, Ottoman, Spanish), with the Christian eschatological imaginary and its ascetical expressions, and penitential practices popular among the medieval mendicant orders that joined the Crusades and missionized the New World.14 The transformations that these encounters cause in iconographic types prompt us to explore the operation of deeper unities in the art object that suggest its ontological resilience, plasticity, and inherence in tradition. Moreover, images that are active in such contexts sustain dynamic theological horizons that cannot be reduced to the institutional, dogmatic, and ideological functions associated with religion.15 These horizons are essential to their ontology.

Tradition is thus the formative and yet elusive domain that keeps an image open and actively engaged with its visual, social, and ideological environments, and at the same time contained within its own iconographic type. In tradition, images circulate freely as theological and aesthetic itinerants, but they also withdraw into their own, indigenous ground, from where these peregrinating energies arise.

This is especially the case with the images addressed in this study that are centered on the great eschatological moment of Christ’s death, and focus on events that the Orthodox liturgy during Holy Week designates with the expression “ta Theia Pathe,” literally the divine sufferings—a litany of betrayals, humiliations, and torments that the singular term “passion” does not fully convey. The concentration in these events of the summative mysteries of the Christian faith (i.e., theanthropy, theoktony (deicide), and theophany as seen in the Transfiguration and the post-Resurrection appearances of Christ), invests them with an extraordinary intensity, and thus with a natural tendency toward polysemy and proliferation.

Of ...