![]()

I | INTRODUCTION |

![]()

1 | Overview and Basic Concepts |

Inference-making is a fundamental and pervasive human process. Nearly every interaction we have, and every decision we make, is likely to involve one or more inferences about ourselves or aspects of our social environment. The variety of these inferences and the conditions in which they occur are nearly limitless. We may infer our own needs, abilities, personality characteristics, moods, and feelings about other persons and events. Similarly, we may infer the traits, abilities, and feelings of others. We may infer how we or others will act in certain situations, and what the consequences of these actions will be. We infer that certain events taking place in our environment are desirable or undesirable, or that they are caused by this or that factor. Moreover, before using information we receive to make other kinds of inferences, we may estimate the likelihood that this information is true.

In each case, these judgments are based upon certain information the inference maker has available. However, the types and sources of this information are as diverse and manifold as the inferences that are based upon it. For example, people’s traits may be inferred from other traits they are thought to possess, from the behaviors they manifest, from others’ behavior toward them, or from the traits, attitudes and abilities of their associates. Inferences about people’s behavior may be based on information about their general traits, their past behaviors, the traits and behaviors attributed to persons in general, knowledge about external pressures to engage in the behavior, or the possible consequences of the behavior for the actor or for others. Moreover, information may vary along more general dimensions. For example, it may be present in the situation, or it may be previously acquired information that the judge recalls from memory; it may be either verbal or nonverbal, either ambiguous or clear, and either consistent or inconsistent in its implications.

It is therefore hardly surprising that a general concern with social inference processes pervades much contemporary research and theory in social psychology, in areas such as impression formation (Anderson, 1968a, 1971a), attribution theory (Bem, 1972; Jones & Davis, 1965; Kelley, 1967), interpersonal attraction (Berscheid & Walster, 1969; Clore, 1975; Heider, 1958), social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954; Latané, 1966), social judgment (Sherif & Hovland, 1961; Upshaw, 1969), and belief and opinion change (for a review, see McGuire, 1968c). However, perhaps because of the great diversity of both the types of judgments that people make and the types of information used in making them, most current theoretical formulations have concentrated upon restricted types of inferences and have considered the effects of only a few types of information. As a consequence, little attention has been given to more general cognitive processes that pervade social judgmental phenomena, and to general theoretical and empirical issues concerning these processes that are common to many types of inferences.

In this book, we will identify many of these general processes and the issues surrounding them, and will explore their role in inference making. Our discussion will not only conceptually integrate many issues that are seldom associated in contemporary social psychological theory and research, but will also raise presently unanswered (and often unasked) questions that are fundamental to an understanding of inference phenomena. As a result, we hope to provide new insights into the possible nature of these phenomena and to stimulate research designed to test the implications of our discussion for a variety of judgments and information types.

When a person (or “judge,” as we will typically refer to him1 in this book) is called upon to infer something about himself or his social environment, he must first identify information that is relevant to this judgment. This information may come in part from the immediate situation in which the judgment is made. However, equally important sources of information are concepts (or instances of concepts) that the judge has stored in memory. This recalled material may have three functions. First, it may have direct implications for the judgment to be made. (For example, the concept that people are generally honest may be used as a basis for inferring that a particular person is honest.) Second, it may be used to encode or interpret the new information presented. Finally, it may be used to construe the implications of newly encoded information for the judgment to be made. Thus, a clear understanding of judgmental processes requires knowledge of the encoding, organization, and storage of social information in memory.

Questions also arise concerning the nature of the judgmental process itself. Different processes may be involved at different times, depending upon the nature of the information presented, the nature of the judgment to be made, and the situational conditions surrounding the judgment. In some cases, a judge may base his inference on the similarity of the total configuration of information he is considering to configurations he has encountered in the past. (For example, I may infer that a new graduate student will make a good research assistant because her blend of personality characteristics and abilities reminds me of a star student I knew in my own graduate school days.) In other cases, the judge may consider the separate implications of several different pieces of information, and may use abstract, higher order rules to combine these implications into an overall judgment.

This book will be devoted to an analysis of these and other questions that are fundamental to a general understanding of social inference. In this effort, we will consider several areas of theory and research that until recently have not been of central interest to most social psychologists. While more traditional areas of investigation will also be covered in some detail, they will often be discussed in different terms, and from a different perspective, than that to which the typical reader may be accustomed.

To provide a perspective for our discussion, we will now consider more formally the various components of the inference situation and the inference process. We will first state more precisely what we mean by an inference. Then we will identify the classes of elements about which judgments are made, and will circumscribe both the nature of the “information” relevant to these judgments and the ways in which it is used. This discussion will anticipate many issues to be addressed in considerably more detail in the chapters to follow. Finally, we will attempt to show the relation of the concerns of this volume to specific theories and research areas in contemporary social psychology.

1.1 COMPONENTS OF THE JUDGMENTAL SITUATION

The basic elements of a judgmental situation consist of (a) the judgment (or inference) itself, (b) the thing being judged (the object of judgment), (c) the information that directly or indirectly bears upon this judgment, and (d) the judge. Let us consider each in turn.

The Nature of Inferences

A judgment or inference about an object may be conceptualized as the assignment of the object to a verbal or nonverbal concept, or cognitive category (Wyer, 1973a, 1974b). In many instances, this assignment will be based upon the similarity of the object’s attributes to those the judge uses to define the concept or to characterize its exemplars. Thus, a judge’s inference that a particular object is a tree may be based upon prior inferences that the object has those attributes that he uses to define membership in the category “tree” (e.g., that the object is “leafy,” “wooden,” “growing in the ground,” etc.). Alternatively, his inference that Italians are intelligent or likeable may be based upon evidence that instances of the cateogry “Italians” have the particular subsets of attributes that define “intelligent” and “likeable.” If an object were known to possess all of the attributes necessary for inclusion in a category, it would presumably be judged to belong to this category with complete certainty. More typically, however, certain relevant attributes of the object are not known. In these cases, the object will be assigned to the category with less certainty or, alternatively, with a subjective probability of less than one.

It is often important to distinguish between the cognitive categories that a judge uses to classify stimuli and the response categories that he uses to communicate this judgment to others. This distinction and its implications have been elaborated elsewhere (Wyer, 1974b; see also Parducci, 1965; Upshaw, 1969). The labels (if any) attached to cognitive categories and those assigned to response categories are not necessarily the same. Thus, when a person is asked to make a judgment, he must not only identify the cognitive category to which the object belongs, but must also decide how to communicate this classification in a language that others will understand and correctly interpret. In an experiment, this language may be not of the judge’s choosing, but rather may be assigned to him by the experimenter. Then, the uncertainty with which a judge reports his inference may be attributable in part to his uncertainty about the meaning of the response alternatives given him as well as to his uncertainty about the cognitive category to which the object belongs. For simplicity we will generally assume that cognitive and response categories are isomorphic, but the reader should recognize that this is an oversimplification, and that in practice the distinction between the two may often be important.

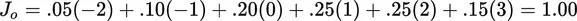

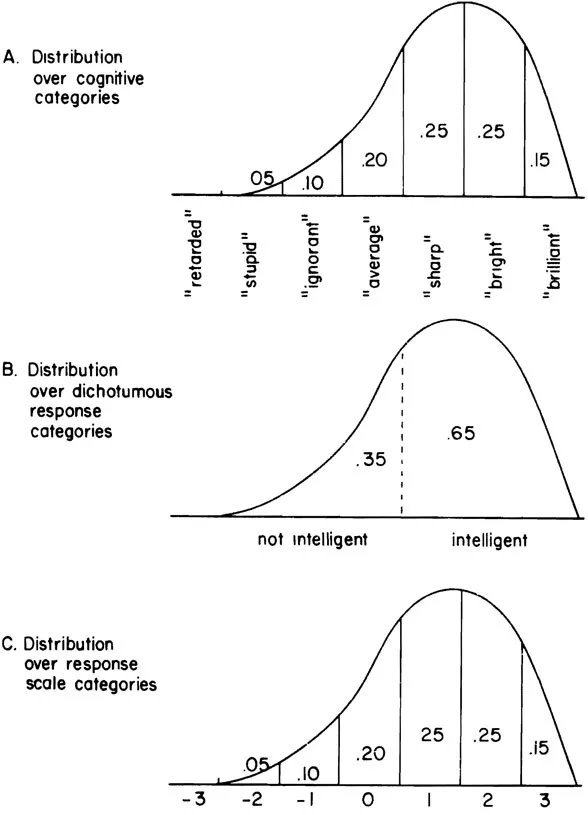

Two general procedures are typically used in experiments to assess judges’ inferences. In one, the judge is given a category name (e.g., “intelligent” or “tree”), and asked to estimate the likelihood that the object in question belongs to this category (e.g., the likelihood that “Italians” are “intelligent”). Such an estimate may be interpreted as probability estimate, or alternatively a belief (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Wyer, 1974b). In the second procedure, the judge is given a set of alternative categories, such as those comprising a numerical response scale, and is asked to assign the object to the category to which it is most likely to belong. These latter inferences are often assumed to be magnitude estimates. Although judgments made using the two procedures may appear to be quite different things, both probably involve the mapping of cognitive categories onto available response categories. Thus, suppose a judge is asked to consider the intelligence of an Italian. The judge may possess several cognitive categories pertaining to intelligence. These categories may or may not have verbal labels (e.g., “stupid,” “ignorant,” “smart,” “brilliant,” etc.), but each presumably has some defining criteria for membership. Based upon his knowledge of Italians, the judge may infer an Italian to belong to several categories with some probability. Assume that the distribution of these probabilities is that shown in Fig. 1.1a. Now, first imagine that the judge is asked to estimate the likelihood that the Italian is “intelligent”. In this case, he must first decide which subset of his cognitive categories should be included in the general response category “intelligent” and which should not. This decision may be based not only upon the judge’s own interpretation of “intelligent,” but also upon how he expects the word to be used by the person to whom he is communicating. Once this decision is made, the judge may then map the distribution of his beliefs into two dichotomous response categories (intelligent or not intelligent) as shown in Fig. 1.1b. His response would then represent the overall probability associated with membership in the subset that fall in the range of “intelligent” (i.e., .65).

Now suppose that the judge is asked instead to rate the Italian’s intelligence along a 7-category scale from −3 to +3. Here again, he may first position the response categories given him so as to include the alternative cognitive categories he assumes are relevant to the judgment, and may map the underlying distribution of his beliefs into these categories, as shown in Fig. 1.1c. His ratings would then correspond to the response category he perceives to be most representative of this underlying distribution. This category might be a “subjective expected value” of the object along the scale in question (for empirical evidence supporting this assertion, see Wyer, 1973a). That is,

where Vi is the value assigned to category i and pi is the judge’s belief that the object belongs to this category. In our example,

Here the judge would assign the Italian an intelligence rating of +1, reflecting his judgment that this rating most closely corresponds to his implicit beliefs concerning Italians.

FIG. 1.1. Hypothetical distributions of beliefs about a person’s membership in (a) cognitive categories pertaining to intelligence, (b) the dichotomous response categories “intelligent” and “not intelligent” and (c) categories along a response scale of intelligence.

Thus, if these mapping processes adequately characterize the processes underlying each kind of judgment, each would reflect the same underlying distribution of beliefs about object membership in relevant cognitive categories. Despite their surface differences in appearance, the cognitive demands and the implications of the two kinds of judgments would be similar.

Evaluative versus Nonevaluative Inferences. A distinction is often made between nonevaluative judgments of an object (e.g., the inference that Italians are “religious”) and evaluative judgments (e.g., the inference that Italians are “good,” or that one “likes Italians”). The latter judgments are often assumed to reflect attitudes toward the object. From the perspective we are proposing, however, there is no fundamental difference between the two types of judgments; each involves the assignment of an object to a cognitive category (“religious,” or “persons I like”) on the basis of certain criteria assumed to define the category. The primary difference may lie in the nature of these criteria. For example, an object’s membership in an evaluative category may be based in part upon information about one’s emotional reactions to the object, while its membership in a nonevaluative category may not be. (We consider the use of emotional reactions as information relevant to a judgment in more detail in Chapt...