eBook - ePub

The Design, Production and Reception of Eighteenth-Century Wallpaper in Britain

- 234 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Design, Production and Reception of Eighteenth-Century Wallpaper in Britain

About this book

Wallpaper's spread across trades, class and gender is charted in this first full-length study of the material's use in Britain during the long eighteenth century. It examines the types of wallpaper that were designed and produced and the interior spaces it occupied, from the country house to the homes of prosperous townsfolk and gentry, showing that wallpaper was hung by Earls and merchants as well as by aristocratic women. Drawing on a wide range of little known examples of interior schemes and surviving wallpapers, together with unpublished evidence from archives including letters and bills, it charts wallpaper's evolution across the century from cheap textile imitation to innovative new decorative material. Wallpaper's growth is considered not in terms of chronology, but rather alongside the categories used by eighteenth-century tradesmen and consumers, from plains to flocks, from China papers to papier mâché and from stucco papers to materials for creating print rooms. It ends by assessing the ways in which eighteenth-century wallpaper was used to create historicist interiors in the twentieth century. Including a wide range of illustrations, many in colour, the book will be of interest to historians of material culture and design, scholars of art and architectural history as well as practicing designers and those interested in the historic interior.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Design, Production and Reception of Eighteenth-Century Wallpaper in Britain by Clare Taylor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

History of Architecturep.19

1 ‘Paper Hangings for Rooms’

The arrival of wallpaper

By the 1750s ‘Paper Hangings for Rooms’ were established on the walls of British houses. Yet defining this new material’s qualities was a challenge for tradesmen and consumers alike. This chapter therefore explores how paper hangings were codified in relation to other desirable interior finishes in terms not only of imitation and cost, but other practical factors too such as durability, and wider trends in design. It was not just imitation, but invention, that could bring commercial success, and here I show how wallpaper provides an example of how new products were created. The chapter examines wallpapers imitating materials such as wainscot, japanning, leather and textiles. It ends by looking at the evidence for the impact of contemporary design discourse on this new material.

Much of the evidence discussed in this chapter comes from advertisements, bills and, in particular, trade cards. Michael Snodin opened up this area of research in a 1986 essay, demonstrating phases in the design of the English Rococo trade card and its links to print culture, claiming that the vast majority were designed and engraved by professional engravers.1 However, Scott has also mounted a persuasive argument in relation to the eighteenth-century French card suggesting that, contrary to Snodin’s position, the designer did have a close relationship with the tradesman or merchant ‘whose wares he was helping to sell’ and that this was especially the case in paper selling and printmaking.2 She has pointed out that ‘pictures’ furnished as cards’ models were tradesmen’s signs, and that, over time, the sign or physical object on the card became less important to its semantic function, becoming reduced to the status of ornament, and eclipsed by the written text. Second, she argues that trade cards functioned less as advertisements for an unknown future purchase, than a record of a past purchase, drawing on evidence that many designs are also found on bill heads and receipts.3 My study of paper hangings’ cards evidences similar developments, where text eclipses (actual) signs, and designs are repeated on bills, suggesting Scott’s model has currency here too and that study of cards can reveal tradesmen’s intentions.

A new commodity: from concealment to the wall

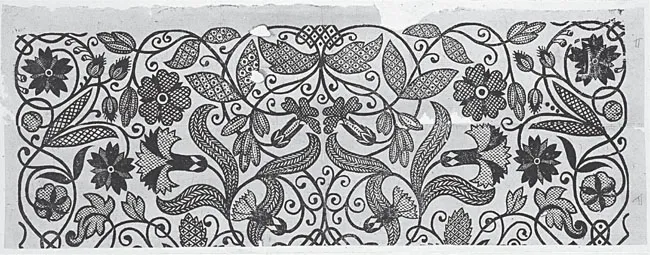

Hanging paper on the wall was a new idea in the late seventeenth century. Paper’s predecessors were either blank, carved or painted wood panelling (wainscot); leather hangings; woven, printed or painted textile hangings or painted finishes. Early wallpaper designs were not intended exclusively for use on the wall, but for far less visible locations, such as lining cased furniture, chests and boxes. These either housed paper objects, particularly deeds, or clothing: protection of ruffs from dust has been suggested as one reason for lining chests with paper. These papers have therefore been called ‘lining papers’, and it has been argued that where patterns are formed from a single sheet they were intended for use inside other objects, rather than on the wall as decoration.4 At least one formal floral design, based on the border of a printed cotton, was evidently printed or at least retailed by a trunk-maker, since it was lettered not only with his trade but also with his name (Roger Hudson) and city (York).5 There was, however, cross-over in these two functions. For example, a paper used to line charter boxes such as that from Corpus Christi College, Oxford (Figure 1.1), has also been found on the wall of a closet.6 The design suggests well developed skills in both pattern drawing and block cutting in the treatment of petals and foliage which are either solidly printed in ink, cross-hatched or printed with a trelliswork pattern recalling lace, reflecting paper’s imitative qualities even at this early date. The printing is also crisp, and the design shows the skills that paper hangers would need on the wall, since the pattern is carefully matched between sheets inside the box. However, the question remains of why papers with these designs were used to line boxes. Certainly the bold single sheet designs would suit smaller objects, their patterns enjoyed either by an individual or a small group, perhaps as part of the uncovering of items of adornment or the unrolling of documents.

p.20

Figure 1.1 Lining paper from charter or deed box, Corpus Christi College, Oxford, late seventeenth century, printed in black ink, English.

Although a few, mainly heraldic, patterns have been found in grander homes, when wallpapers moved from concealment to visibility on the wall they were more frequently hung in merchants’ houses, especially in the towns which clustered around the edge of London such as Watford and Epsom, or port towns along the East Anglian coast. This trend, of merchants as early adopters of new decorative tastes in wallpaper, continued throughout the eighteenth century. However, as early as the 1680s wallpapers were also in limited use in closets in some aristocratic homes, suggesting the decoration of this room was an entry point for wallpaper in aristocratic as well as merchants’ homes. These single sheet designs include a number printed with motifs of flowers and fruit which have their origins in black silk embroidery on a linen ground. Indeed, it is possible that the one does not imitate the other but that they share a common source, or even that papers provided patterns for embroiderers, since when the pattern was printed on paper it was neither enlarged nor reduced in scale.7

p.21

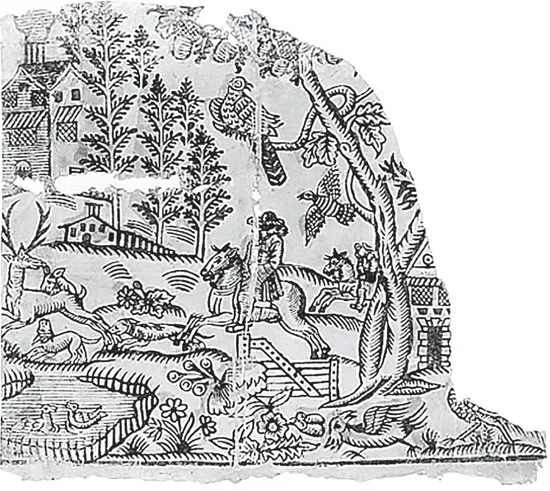

Figure 1.2 Wallpaper imitating tapestry, associated with Aldford House, Park Lane, London, late seventeenth century, stencilled in yellow, red and green over black ink printing, English.

Paper might be able to offer pattern, but colour was another matter. Early papers could be stencilled in colours, but the range of tones was limited (blue, orange, pink and green have all been recorded) and the colours were transparent, so lacked both depth and opacity. There were also issues with registering the print, since the black outlines did not always coincide with the coloured area beneath. This was the case in another paper that spans the boundary between concealed lining and decoration on the wall. The so-called ‘Aldford House’ pattern stencilled in yellow, red and green consists of figurative scenes set in landscapes peopled by animals, buildings and formal gardens, all surrounded by a border (Figure 1.2). It is intended to imitate tapestry, specifically French papiers de tapisseries, and is known to have been pasted on the wall (at The Shrubbery, Epsom) as well as lining chests and deed boxes including a chest dated 1735 at Dunham Massey, Cheshire.8 Figurative sheets, then, were also part of wallpaper’s library of images from the first.

However, in the first half of the eighteenth century, these single-sheet prints were superseded by more ambitious productions. Technical and manufacturing innovations are often cited as the key issue in wallpaper’s expansion, and did result in a much greater range of patterns, colours and finishes being made available. Once single sheets were joined to form a length or piece 12 yards long and around 22 inches wide (a measure also derived from textiles) more ambitious, large scale patterns which could repeat across more than one length could be produced. Some tradesmen still hedged their bets; the stationer George Minnikin of Aldersgate advertised on his trade card of c.1680 that he sold paper hangings ‘both in Sheets and in Yards’, suggesting that at this early date there was still demand for both measures.9

p.22

Study of surviving examples suggests that arou...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Design, Production and Reception of Eighteenth-Century Wallpaper in Britain

- The Histories of Material Culture and Collecting, 1700–1950

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Plates

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 ‘Paper Hangings For Rooms’: The Arrival of Wallpaper

- 2 A Contested Trade

- 3 Imitation and the Cross-Cultural Encounter: ‘India’ and ‘Mock India’ Papers, Pictures and Prints

- 4 In Search of Propriety: Flocks and Plains

- 5 Challenging the High Arts: Papier MâChé, Stucco Papers and ‘Landskip’ Papers

- 6 ‘Our Modern Paper Hangings’: In Search of The Fashionable and the New

- Epilogue: ‘Pleasing Decay’ – The Rediscovery of Eighteenth-Century Wallpapers

- Appendix 1: List of Principal Wallpapered Rooms Discussed, C.1714–C.1795

- Appendix 2: List of Eighteenth-Century London Paper Hangings Tradesmen Discussed

- Bibliography

- Index