- 156 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Orientalism, Masquerade and Mozart's Turkish Music

About this book

Matthew Head explores the cultural meanings of Mozart's Turkish music in the composer's 18th-century context, in subsequent discourses of Mozart's significance for 'Western' culture, and in today's (not entirely) post-colonial world. Unpacking the ideological content of Mozart's numerous representations of Turkey and Turkish music, Head locates the composer's exoticisms in shifting power relations between the Austrian and Ottoman Empires, and in an emerging orientalist project. At the same time, Head complicates a presentist post-colonial critique by exploring commercial stimuli to Mozart's turquerie, and by embedding the composer's orientalism in practices of self-disguise epitomised by masquerade and carnival. In this context, Mozart's Turkish music offered fleeting liberation from official and proscribed identities of the bourgeois Enlightenment.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Orientalism, Masquerade and Mozart's Turkish Music by Matthew Head in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Classical Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Orientalism, History and Theatre

Said’s insistence upon the ‘the Orient’ in Western scholarship as an imaginative, discursive construct grounded in no imminent geographical reality but serving rather as a fantasised antithesis is almost always acknowledged in musicological writings on Orientalism.1 But the relevance of Orientalism, an anti-imperialist critique of Western scholarship, to eighteenth-century musical ‘exoticism’ has not been worked through in even a provisional way. To some extent, Said invites extension of his critique of Orientalism as a scholarly discipline (now more often termed Near-Eastern studies) by de-emphasising disciplinary boundaries between scholarship and the imaginative representations of the East in literature and the arts. The representations proffered in these different media and contexts, Said suggests, possessed a degree of stability across different media, disciplinary boundaries and historical periods; they shared a vocabulary of images and ideas, a series of tropes about ‘the Orient’ that enhanced each other’s appearance of truth through their mutually reinforcing repetition. Overlap between scholarly writing and musical and literary representations is inherent in Said’s central metaphor for Orientalist ‘knowledge’, that of ‘theatre’:

The idea of representation is a theatrical one: the Orient is the stage on which the whole East is confined. On this stage will appear figures whose role it is to represent the larger whole from which they emanate. The Orient then seems to be, not an unlimited extension beyond the familiar European world, but rather a closed field, a theatrical stage affixed to Europe…. In the depths of the Orientalist stage stands a prodigious cultural repertoire whose individual terms evoke a fabulously rich world: the Sphinx, Cleopatra, Eden, Troy, Sodom and Gomorrah, Astarte, Isis and Osiris, Sheba, Babylon, the Genii, the Magi, Nineveh, Prester John, Mahomet, and dozens more.2

At stake in Said’s metaphor of theatre is not only the neutrality and objectivity of official, scholarly knowledge but, more broadly, the moral and intellectual values of truth, sincerity and authenticity in which the West has declared itself invested but which it transgresses in the act of representing the East.

The metaphor of theatre marks ‘knowledge’ of the ‘Orient’ as staged by and for a Western audience. Conversely, staged representations, like their literary and musical counterparts, were also forms of knowledge about Turkish music and culture. Indeed, for some members of a late-eighteenth-century Viennese operatic audience, the alia turca style of Gluck, Haydn and Mozart was the only source of knowledge about Turkish music.3 Thus despite its often comic character it possessed a subliminal authority and persuasive power as a representation. There were of course travellers and scholars with more detailed, sometimes first-hand knowledge of Turkish music for whom such processes of generalisation and imaginative meta-musical suggestion may have held little sway.4 Nonetheless, for some members of Viennese theatre audiences, Turkish music may have served by synecdoche as that detail which signified a cultural whole. Though often a representation of Janissary music specifically, the alla turca style tapped into and retold tropes that pertained more broadly to Western conceptions of the Ottoman empire. A question formed in the wake of Orientalism is to frame music as knowledge and inquire ‘what is Mozart’s Turkish music telling the audience about Turkish music proper and the Ottoman empire as a whole?’

The metaphor of theatre is invoked by Said to resist scholarly claims to objectivity and truth. But what of Orientalism in theatre, or in opera? That is, what happens to Said’s theory when his metaphor becomes an actual context? One of the things that happens, even for a musicologist struck with the power of Said’s arguments, is that a new set of issues enters the frame—issues of genre, audience, singers, acting styles, staging, compositional craft. These issues, which the discipline of musicology furnishes for any student of opera, do not negate Said’s thesis but they do tend to displace it. Once we start to engage with these issues it may be difficult to retain ‘the Saidian impulse’, in Everist’s phrase. This is so despite the fact that theatre’s construction of difference as a kind of masquerade, an artifice of representation, a play with signs, has particular resonance with conceptions of Otherness in the Enlighten-ment. Sometimes, a musicologist works at a level of musical detail that can make Said’s thesis of a binary division of Self and Other seem too broad to account for what matters most: Mozart’s music. For example, the generic and stylistic eclecticism of Die Entführung, maximised through self-contained numbers punctuated by dialogue, works against a single, unified musical vantage point, a secure ‘Us’ from which to gaze upon ‘the Other’. All Mozart’s Viennese operas are distinguished by generic hybridity and by the (dramatically telling) variety of musical types and topics, but Die Entführung stands out as a work in which this variety is not subject to even a provisional congruence. In their arias and duets, the characters seem to reveal that—the temporary illusions of ensembles aside—they do not share a musical language in which to speak to each other. Within this decentring musical world, a range of characters is assembled (Ottoman, Spanish and English; noble and servant; free and incarcerated). Further, the binary axis of ‘East’ and ‘West’ is both articulated and reversed: articulated through the representation of Osmin as barbarian, reversed by Pasha Selim’s personification of European-Christian aspirations and by his description of Belmonte’s (Spanish) father as a tyrant and barbarian. Binary opposition operates not only between Europe and Ottoman Turkey but within the (equivocal) ‘Us’ of the Spanish characters who are divided according to social position and gender. What I shall argue, however, is that these disruptions are part and parcel of Orientalism as a theatrical and musical practice; they are not evidence that Orientalism has nothing to teach us about Mozart.

Indeed, in theatrical contexts, the crossing of binary oppositions between Self and Other is of particular interest. Musically, Pedrillo’s Hispanised Romance, ‘In Mohrenland’, is exoticised beyond the Turkish colour of the Janissary choruses through texture (the plucked string accompaniment simulating Pedrillo’s mandolin), ambiguity over the tonic as B minor or D major, and the related way in which the music ‘slips’ between both keys and between chords, highlighted by metrical placement, a third apart (Ex. 1.1).

The first four bars, for example, slip from an opening B minor to D major. But more than this, bars 1–3 highlight, as well as in Schenkerian terms prolong, V of B minor. This F-sharp chord creates its own, more richly chromatic, third relation with D major (involving a shift from A♯ to A♮), such that the D major chord in bar 4 is doubly approached, from above and below, by thirds (F-sharp major and B minor respectively).5 These third relations, revisited in bars 9–10 with the movement from A major to C major, are early examples of the use of third relations for purposes of strangeness of affect and identity. To a lesser extent, they also characterise the Janissary Chorus of Act 1, which momentarily enriches its C-major tonic with a bifocal A minor/C major opening. In quite a different context, Bizet would later employ similarly ambiguous third-relations, and tonic obfuscation, to describe Carmen’s sexual and racial Otherness, to mark the operations of desire.

Ex. 1-1 Die Entführung, K. 384, Tn Mohrenland’ (Pedrillo), bars 1–7

Pedrillo’s Romance is doubly characterised as Spanish and Turkish—a dramatically apt ambiguity given that this is a song by a Spaniard about an abduction from Turkey. This ethnomusicologically dubious conflation of Spanish and Turkish colour accords with contemporary European scholarship on Turkish music. Charles Blainville drew a specific analogy between Turkish airs, sung to an improvised accompaniment, and the amorous songs that Spaniards sing beneath ladies’ balconies.6 Both Blainville’s remarks and Mozart’s treatment reveal that Spain was already in the eighteenth century subject to exoticisation. True, Mozart is not dealing in the touristic images of bullfights and flamenco dancers that would characterise Spain for nineteenth-century Europe.7 But nor is he focusing on the Spanish conquest of South America—the dominant image of Spain in eighteenth-century opera.8 In Pedrillo’s Romance the Austro-German image of Spain has already turned to an image of Spain that focuses on Moorish elements. Spanish imperialism, and thus Spanish power, is relegated to the ‘before’ of the operatic plot: the ruthless occupation of North Africa by Belmonte’s father. Mozart’s exoticisation of Spain is remarkable because this exoticisation is usually said to begin with its disempowerment through the Napoleonic invasion and occupation of 1808–13.9

As a miniature replay of the opera in which it is embedded, Pedrillo’s Romance is at once integral and set apart. The Romance is an estranged narrative moment in which the opera itself is beheld, as if at a distance. As such it serves a similar strategy as the Orientalism of the opera itself, which distances the world of the opera from the world of the audience. Orientalism, like the nested stage song echoing the whole, is an artifice that heightens critical attention and pleasure.

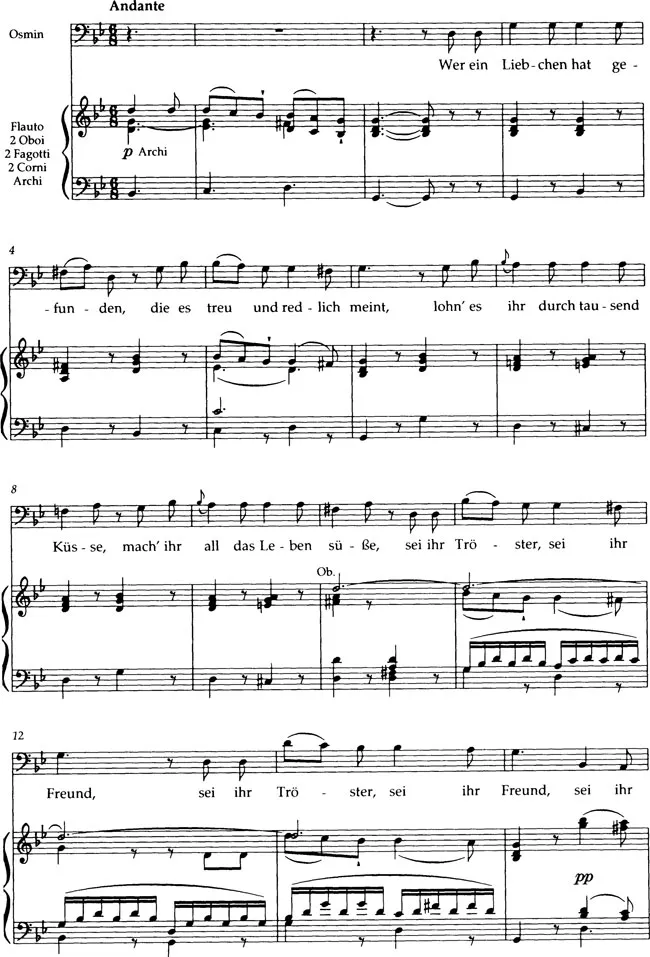

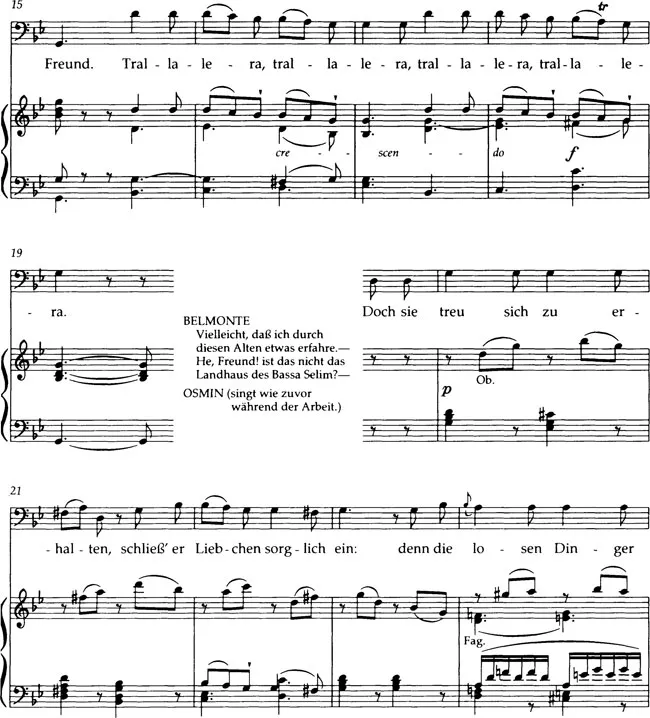

The identity of Pedrillo’s Romance is richly ambiguous in terms of Self and Other. Formally and in its subject matter it casts back across the acts to Osmin’s opening lied ‘Wer ein Liebchen’ (Ex. 1.2)

Indeed, the connections are close enough to set up, between these numbers, a symmetrical and thus to some extent static formal architecture, one that (like Pedrillo’s Romance itself, which delays the proceedings sufficiently to contribute to the lovers’ capture) undermines the forward momentum of the escape/abduction scenario. Whereas Osmin’s lied was about the need to lock up the sweetheart, Pedrillo’s Romance is about the need to set her free. Both are strophic stage songs and, in a play upon the relationship between drama and musical form, both singers are interrupted after internal stanzas by Belmonte, who is impatient to move the action on. A trope of the timeless and static Orient versus the ‘progressing’ West is suggested by these interruptions, though the endotic point (concerning song form, genre and drama) is also conspicuous.10 Generically tied to the singspiel, the strophic songs of Osmin and Pedrillo entertain a nostalgia for a dramatic naivety that permitted ‘drama’ (and the type of innovative musical structures Mozart highlights in his discussion of Osmin’s rage) to stop still as a character delivered a song, stanza by stanza. Both songs are in the lilting 6/8 of the Siciliana, a Baroque dance type that Mozart here invests multiply with connotations of the rustic, the antique and the exotic.

If Pedrillo crosses an Orientalist boundary between ‘Us’ and ‘Them’, Osmin is also mobile within the now idealising, now derogatory, imagery of Orientalism’s Others. Osmin appears, in his first stanza, as a noble savage—his rustic measure, his ‘folksong’ melody, lulling chaconne-type bass, and ‘tralalera’ refrain suggesting an innate disposition for song.11 In a moment of intense voyeurism, the audience observes him in tranquillity, as he sings a stage song that he does not even realise is being overheard. It is only with Belmonte’s repeated interruptions that his temper is roused. These aspects of Osmin seem to go unnoticed by modern critics. They are preoccupied with his threats of torture and dismemberment—though it has not been noted, to my knowledge, that Osmin is simply fantasising here the types of public punishment that Joseph von Sonnenfels had recently sought to outlaw in favour of ‘humane’ and ‘rational’ incarceration but which were still administered in Joseph II’s reign.12

Ex. 1-2 Die Entführung, K. 384, ‘Wer ein Liebchen’ (Osmin), bars 1–24

Representation and Power

If Orientalism invites consideration of Mozart’s Turkish music as a form of knowledge it demands that the relations between knowledge and power be interrogated. Representation emerges as the primary focus of critique in Orientalism. Said not only refuses representations of the colonised in the time of empire their claims to descriptive neutrality, but sees power operating in the textuality of representation and at a stage prior to the administration of overseas territories. Representation is not just seen to silence—to speak for those not permitted to speak—but to be one and the same with overseas domination: it restructures and reorganises ‘the Orient’.13 Eighteenth-century Orientalist scholarship is described as an originating site of control, one that history would move from the level of imaginative to physical geography.14

Said draws here upon a critique of Western knowledge as power associated particularly with the Frankfurt School of Horkheimer and Adorno. His remarks are a specific instance of the broader contention about the imperialism of European relations with its objects of enquiry: the body, the natural world, music, non-European culture and so on. In this contention, however, textuality and representation are not accorded the transcendental status Said accords them. Said domesticates a more radical critique of Western knowledge, and its keyword ‘reason’ as totalitarian in character and in implementation: a critique that is fundamental to his thesis but which his liberal humanism prevents him from exploring. Instead, Said attaches a critique of the Western construction of the Orient to a new-critical emphasis on text and textuality that is less threatening, and more familiar to, an academic Anglo-American readership. Even Said’s use of Foucault retreats from the latter’s more far-reaching critique of Western knowledge as governed according to historically specific regimes of discourse. Said treats the taxonomic moves of Orientalist scholarship (d’Herbelot’s alphabetised guide to the East) in isolation from what Foucault calls the taxonomic regime that governed official ways of knowing and describing the world. By isolating Orientalism as a special case, Said is able to ignore the intellectual problems inherent in the attempt to reduce Western knowledge to the single transcendental hermeneutic of power, just as he is able implicitly to leave other areas of Western culture unaffected by his critique of Orientalism.

Cross-cultural representation in the arts always involves an experience of mastery, but its politics are not monolithic and cannot be reduced to a grand hermeneutic of power: such representations are a function of all the elements that make up a culture—political context, modes of circulation, the totality of formal/generic elements of the text, reading practices and use. A textual strategy, such as parodic farce, takes on different connotations depending upon who is doing the representation and who is represented. Representational codes or signs may be passed from one context to ano...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Music Examples

- Introduction Mozart’s Orientalism, Osmin’s Rage

- 1. Orientalism, History, and Theatre

- 2. Mozart’s Orientalism: Scope and Contexts

- 3. A Copy of a Copy: Mozart’s Sources

- 4. Turkish Music, Masquerade, and Self-Othering

- 5. Emplotting Turkish Music: Sonata in A (K. 331 / 300i)

- 6. Mozart Imperialisms

- Sources Cited

- Index