![]()

Part I

Theoretical approaches

![]()

1 Middle powers

A comprehensive definition and typology

Tanguy Struye de Swielande

Scholars are very divided on the definition of a middle power. Since the end of World War II, many scientific articles and monographs have been dedicated to the subject; yet no one appears to agree on a common definition or on common characteristics. Scientific literature can be divided into four pools of study on middle powers, each with its own perspective: function, capabilities, norms or behaviour. Yet despite this diversity, some approaches have been somewhat overlooked, which are essential to define a middle power. Additionally, I argue that the contemporary vision of the definition of middle power remains too impregnated with a Western paradigm: the confrontation between states with the same political, cultural and ideological concepts. This ethnocentric vision imperfectly reflects the reality and restrains our comprehension of middle powers. I endeavour in this chapter to surpass these two limitations, by proposing a new definition of middle powers valid for both traditional (Western) middle powers and non-traditional or emerging (non-Western) middle powers.

To achieve this objective I adopt a holistic approach. Indeed paradigm-bound or fragmented research has demonstrated its limits in the study of middle power. It is necessary to link different concepts from different paradigms to stress the conceptual complexity of middle powers and to establish closer connections to other disciplines (such as management theory as I do in this chapter). A pluralistic approach provides stronger explanations while remaining analytically and intellectually rigorous. Consequently, I resort to various existing theories to answer the following question: what are the indispensable characteristics of a middle power nowadays to obtain an integrative definition?

Although many scholars have defended one approach in particular, I contend that a variety of approaches can complement each other and bring us closer to an integrative definition. In the first section I propose an integrative definition based on existing and new determinants of middle powers. This definition retains the five most critical determinants of middle powers that differentiate the latter from small or great powers. I realise that the definition I propose will need to be refined and detailed gradually through testing. The second section goes a step further and presents a typology, inspired by Wendt’s research, to differentiate middle powers based on their distinctive behaviour. By developing this new typology I include into existing typologies the domestic environment and the country leaders’ perception of their security environment.

A new definition

The first part of this chapter identifies and explains the five characteristics of middle powers – capacities, self-conception, status, regional and systemic impact – investigating the last two in greater detail. I explain their significance and necessity in the process of outlining an integrative definition that would apply for all middle powers.

First, a middle power owns medium range capacities, both material and immaterial, although the literature tends to limit its focus on material ones. This perspective confines middle powers to a deterministic approach and does not explain why two similar middle powers such as Australia and Canada behave differently regarding various events in time (example: War in Iraq in 2003). For Kalevi Holsti, “such measurements and assessments are not particularly useful unless they are related to the foreign policy objectives of the various middle powers” (1964, p. 186). Although the “position indicators” cannot be neglected or overlooked, they are insufficient by themselves to define a middle power (Carr, 2014, p. 73). Capability is always the “capability to do something; its assessment, therefore, is most meaningful when carried on within framework of certain goals and foreign policy objectives” (Holsti, 1964, p. 186). Thus, middle powers operate in a dynamic process and relationship.

A second necessary characteristic to define a middle power is its self-conception: a middle power has to consider itself a middle power. Politicians and diplomats from Canada and Australia at the end of World War II have developed this approach originally. Middle powers do not stand midway only based on an “objective definition”, it is their self-perceived role in the international hierarchy that places them there also (Hey, 2003, p. 2).

Nonetheless, self-perception is not sufficient: to be a middle power, a country also has to be recognised by others as such. As Vandamme explains in Chapter 13 of this volume:

(Welch Larson, Paul & Wolforth, 2014, p. 11)

Hence, the third characteristic is status, reflecting the recognition that the audience of states grant to a certain state; status captures the need of a country to be recognised and respected in the international hierarchy of states (adapted from Magee & Galinsky, 2008). It also highlights that a country’s position becomes a reality through external recognition. Moreover, because middle powers have a “desire for greater international status” (Chapnick, 1999, p. 76), they seek to “obtain international recognition as big contributors in international politics” (John, 2014, p. 328).

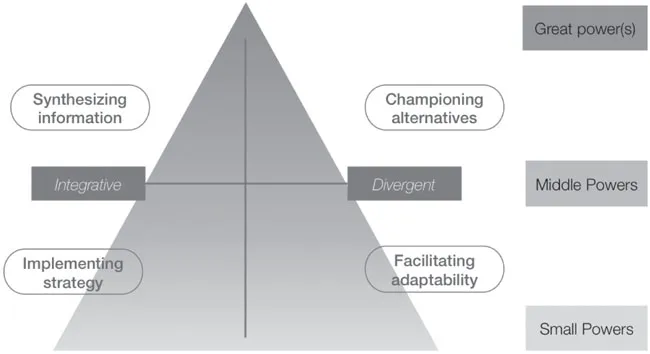

The fourth characteristic is the systemic impact, i.e. “the ability to alter or affect specific elements of the international system in which (middle powers) find themselves” (Carr, 2014, p. 79). Andrew Carr defines middle powers as “states that protect their core interests and initiate or lead a change in a specific aspect of the existing international order” (Ibid.). Additionally, drawing from mid-level management theory (Guth & MacMillan, 1986; Floyd & Wooldridge, 1997 Wooldridge, Schmidt & Floyd, 2008), I understand middle powers as forming in a hierarchical order the indispensable link between the bottom and the top. Middle powers are recognisable by their access/relation to great powers, coupled with their (regional) expertise and influence on small powers, operating up and down the hierarchical system. I refer to the framework developed by Steven Floyd and Bill Wooldridge (1997) in management studies regarding the middle-up-down approach to illustrate this point (see Figure 1.1). The middle-up-down approach establishes that where an upward strategy is used to influence the great powers/leaders, a downward strategy is used to influence small states.

Thus, to paraphrase Floyd and Wooldridge (1997, pp. 465–485; Wooldridge, Schmidt & Floyd, 2008, pp. 1190–1221), middle powers are seen as upward information synthesisers and strategy implementers (classical top-down approach). But middle powers are also facilitators of adaptability (niche diplomacy, mediation, bridge-building, innovative practices) with room for manoeuvre without facing any melding from the great powers (bottom-up approach). They are closer to day-to-day regional interactions and realities and have better knowledge of regional tensions or realities. Middle powers can thus detect opportunities and develop innovative approaches more quickly (regional approach) than the great powers (global approach). Furthermore, middle powers can champion alternatives upward to influence the great powers. As David Dewitt rightly suggests, “a major hallmark of a middle power [is that it can] always get a hearing from a major power but be trusted by smaller states” (as quoted in Hurst, 2007). This position implies a certain degree of autonomy towards great powers and “do things that a great power doesn’t agree with, or even opposes, without the backing of another great power” (White quoted in Scott, 2013, p. 16). While most scholars have so far considered middle powers as status quo powers or (passive) followers (to stand for), this approach in fact contends that they can also be critical followers, toxic followers (see on followership literature: Chaleff, 2003; Kellerman, 2008; Howell & Mendez, 2008; Carsten & Bligh, 2008), potential “reformists” (Jordaan, 2003) or swing states (to stand up) (see Vandamme & Struye 2015; see also Jonathan H. Ping, Chapter 16).

Additionally, to facilitate this middle-up-down approach, a lateral strategy to impact peers reinforces their influence on small and great powers. As Geoffrey Hayes writes, “middle powers are knights, bishops and rooks in international relations who cannot dominate and thus have to deploy their strength in combination with others” (Hayes, 1994, p. 14). The international system is characterised by vertical and horizontal relations that are interconnected in a “stable network of patterned interactions” (Astley & Sachdeva, 1984, p. 104). In that sense, the more a middle power constitutes a node in the network, the more it gains power because “(its) immersion in multiple interdependencies makes (it) functionally indispensable” (106). Such “intraorganisational power”, namely network centrality,

(106)

As the EAI Middle Power Diplomacy Initiative summarises in its key findings:

(Lee, Chun, Suh & Thomsen, 2015, p. 6)

However, if middle powers can play a critical role in the international system, their leeway depends “to a large extent on the form and state of the international system to which they belong” (Holbraad, 1984, p. 212–213). States operate in dynamic processes and relationships; consequently, “each type of situation created by the dynamics of this interaction – determined by the number of great powers and the level of their relations – presents to a range of theoretically possible roles to middle powers in the system” (Holbraad, 1984, p. 8). This latitude appears greater in a unipolar or multipolar system, or even in a system in transition than in a (rigid) bipolar world. If during the Cold War, the role of middle powers proved limited and restrained (bipolar world and closed alliances), a world in transition, characterised by transitional dynamics (volatile and loose alliances) opens a window of opportunities. As Andrew Cooper mentions, the role of a middle power is rather dynamic than static and it must be “constantly subjected to adjustments to fit the evolutions of the international system” (1997, p. 8).

Related to the precedent characteristic, the fifth one, the country’s regional impact, relates to the direct regional environment of the middle power, namely its Regional Security Complex (RSC). Buzan and Wæver (2003), who develop this theory, retain four categories of regional settings: (i) standard RSC, (ii) centred RSC, (iii) great power RSC, (iv) no RSC. It is evident that a region dominated by a great power or superpower (ii, iii) denies the possibility for a middle power to be a regional power1 – a well-known example is Canada – but it still has a regional impact (see above the middle-up-down approach). Consequently, I contend that every middle power does not have to be regional power per se to have a regional impact, because of the configuration of the regions. A regional impact would mean, in the best-case scenario, to combine both regional power status and middlepowermanship. In the worst-case scenario it would translate in practice through developing counterweights (balancing, hedging, leash-slipping, blackmail), regional niches, mediation,2 multilateralism, regional organisations,3 to successfully manage the relationship with the great or superpower in its RSC. Additionally, the fact that the regional impact of the middle power would be reduced due to the structure of the RSC does not mean that the middle power would have no systemic impact – again Canada is a good example.

By building on the preceding elements, this analysis proposes the following definition of middle power: a state with medium-range capabilities (material and immaterial) at its disposal to protect its core interests. Endowed with regional impact,4 it is – at least – capable of revising specific elements of the systemic order,5 It must identify itself as a middle power (self-conception) and be recognised by others in this perceived role. To resume the discussion above and the definition, five necessary properties or determinants are selected to define whether a state is a middle power or not: (i) medium range capabilities, (ii) regional impact, (iii) systemic impact, (iv) self-conception and (v) status.

These theoretical assumptions will need to be tested through further empirical research in relation to a sample of states and be improved and refined. Testing will not only determine the correctness of the definition but also its practical applicability. Some of the determinants will be easier to test than others. It will for example not be easy to test or observe directly a country’s status. To evaluate the determinants, a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods should be used. Concerning medium range capabilities, material and immaterial determinants of power should be considered by using different existing rankings and indexes.6 For the other properties, quantitative and qualitative discourse analysis would be effectiv...