![]()

Part 1

Setting the scene

![]()

Chapter 1

The case for new pedagogies in engineering education

Rhys Morgan

Throughout history humankind has managed to overcome the many barriers it has faced in order to prolong life and improve our existence on the planet. These engineering achievements are well documented. The earliest examples can be identified as primitive stone tools for hunting and preparation of food to the control of the elements; in particular the direction of water for irrigation, farming, and sewerage and the creation of monuments and other early infrastructure. Later followed the ability to harness heat energy that led to basic working of metals, and casting and shaping for creation of tools, weapons, and ornaments.

Skipping forward several thousand years, it is worth reflecting on just a few just profoundly impactful innovations from the 20th century; electrification, the automobile, the aeroplane, radio and television, integrated circuits and computing, rockets, and spacecraft. There are of course many more, but the extraordinary impact on humanity from just these few alone has changed life for billions of people that inhabit our tiny fraction of the universe.

Many advancements in engineering have had unexpected and unintended consequences on our lives in ways we could never have imagined. The laser, for example, first created in 1960 by Theodore Maiman at Hughes Research Laboratories in the USA, which has had such profound impact on so many aspects of life, from telecommunications to advanced manufacturing to entertainment, was initially mockingly described as a solution waiting for a problem! Another surprising example is the advent of air conditioning, which has transformed our world in a way well beyond its immediate intention. The air conditioner was developed in 1902 by an inventor named Willis Carrier and was created to prevent paper wrinkling in the heat and humidity of the printing and lithography company in which he worked in Brooklyn, New York. Some years later, after air conditioning units had spread throughout industry, they became popular in movie theatres and cinemas, and the cool environment of the theatres became an attraction in themselves to allows the masses to cool down in the summer heat. Various commentators argue that it is not a coincidence that the Golden Age of Hollywood began around the same time. But perhaps most fascinating is the fact that because of the advent of home air conditioning, many Republican Americans were able to migrate to southern and western states which were previously too hot and humid to comfortably inhabit in the summer months. This migration brought affluent pensioners to the southern states, which in turn skewed the US Electoral College system in favour of the Republican Party in the 1980s and led to the election of Ronald Reagan and several subsequent Republican presidents, including Donald Trump today. I allow the reader to judge for themselves whether they believe air conditioning has therefore had a worthwhile impact on humanity!

The challenges for engineering in the 21st century

The 20th century saw the greatest engineering achievements that humankind has created, and have arguably improved virtually every single aspect of human life. This new century holds as many challenges as those in the past and, as the population continues to grow, the challenge of sustaining civilization’s continuing advancement, while continuing to improve the quality of life for the expanding global population, will become ever more pressing.

In 2008, the National Academy of Engineering in the United States of America published the Grand Challenges for Engineering. Drawing on input from leading engineers and technological thinkers from around the world, 14 goals for improving life on the planet were identified. The vision of the grand challenges called for “Continuation of life on the planet, making our world more sustainable, secure, healthy and joyful.”

The global grand challenges idea captured the imagination of the profession, engineers and academics, policymakers, and students across the globe. Since the publication of the initial Grand Challenges report, there have been three international summits held in London (2013), Beijing (2015), and Washington (2017). An undergraduate student programme has been developed and momentum continues to build as more young people beginning their engineering careers recognize the role that engineering serves to society and people and the need for a global mindset to work and engage with engineers anywhere in the world in the 21st century.

Table 1.1 Grand Challenges for Engineering (NAE, 2008)

Make solar energy economical | Reverse-engineer the brain | Secure cyberspace | Restore and improve urban infrastructure |

Provide access to clean water | Engineer better medicines | Prevent nuclear terror | Enhance virtual reality |

Develop carbon sequestration methods | Advance health informatics | Engineer the tools of scientific discovery | Advance personalized learning |

Provide energy from fusion | Manage the nitrogen cycle | | |

Table 1.2 UN Sustainable Development Goals (2016)

1. No poverty | 2. Zero hunger | 3. Good health and wellbeing | 4. Quality education |

5. Gender equality | 6. Clean water and sanitation | 7. Affordable and clean energy | 8. Decent work and economic growth |

9. Industry, innovation, and infrastructure | 10. Reduced inequalities | 11. Sustainable cities and communities | 12. Responsible consumption and production |

13. Climate action | 14. Life below water | 15. Life on land | 16. Peace, justice, and strong institutions |

17. Partnership for the goals | | | |

More recently, in 2016, the United Nations launched the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (see Table 1.2). The SDGs, call for actions across all countries to end all forms of poverty, fight inequalities, and tackle climate change, while ensuring no one is left behind.

Again, engineering will play a crucially important role in achieving many of these goals. Clearly, addressing issues such as clean water and sanitation, sustainable cities and communities, and affordable clean energy require engineering domain knowledge and skills. But the role of technology in reducing poverty, improving opportunities for education, increasing access to better healthcare, and many others will also rely on engineers to address these challenges.

A fundamental misunderstanding

Despite this role that engineers have had in shaping humanity’s life on the planet and the key part they will play in addressing the 21st century’s challenges, society still appears to misunderstand the profession. The definition from the Oxford English Dictionary provides an excellent illustration:

Engineering: Noun: The branch of science and technology concerned with the design, building, and use of engines, machines, and structures.

It is worth reflecting at this point on the etymological root of the word, engineer. It comes from the Latin, ingenium, which means ‘genius’ or more generally, talent, natural capacity, clever, and problem solver (McCarthy, 2009). It leads to well-known derivatives such as ingenious and ingenuity – words that we often associate with engineering solutions. In many European countries, the name engineer is still spelt with an i, such as ingenier (French), or ingegnere(Italian), reflecting the Latin root more precisely. The word engine with an ‘e’ itself appears around c. 1300 and has its origins in the creation of instruments of war, specifically armaments that were developed in the middle ages. The use of the word engine for a mechanical device converting energy to mechanical power (in particular steam) did not come about until the early 19th century and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.

We might say – oh, how different the discipline might be viewed then but for a single letter! One might imagine young people engaged in feverish competition to gain places to study how to become ingenious at university!

But why does this matter? Today, in the UK certainly, where we discarded the letter ‘i’ in favour of ‘e,’ we find the public more generally associating engineering with the grease, oil, and tools that are synonymous with machines that transfer energy to power – notably reciprocating engines found in vehicles and other forms of transport. This has been exacerbated by a number of other skilled trades identifying themselves as engineering, and while exhibiting some aspects of engineering knowledge and skills, many in the engineering community argue the occupation of the name engineer by technical workers has done irreparable damage to the status of the profession and undoubtedly has been a contributing factor to the UK suffering from an engineering skills shortage.

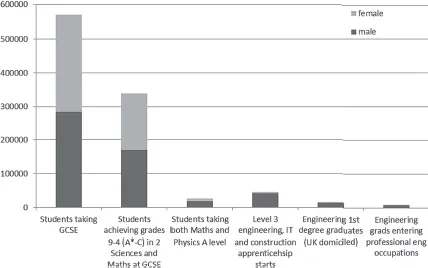

Engineering UK, the body which analyses engineering skills demand and supply data for the engineering profession, highlights in its 2018 annual report a demand of 124,000 engineers and technicians over a ten year period between 2014 and 2024. Assuming a flat annual demand profile, this means 124,000 engineers and technicians each year (The State of Engineering, 2018).

While this figure appears extraordinary at first glance, it is actually not as unreasonable as it might appear. Engineering in the UK is substantial. Around half of the UK’s exports come from manufactured goods and the sector accounts for around 25% of GDP (RAE, 2015). According to national statistics data, there are some 4.5 million people working in engineering occupations in the UK (The State of Engineering, 2018). Assuming an average 40-year working life, this would require the replacement of around 112,500 engineers and technicians each year just from retirements alone. Add to that any additional demand due to expansion of particular sectors, such as software and digital engineering, and it becomes apparent how quickly the demand figure can be reached.

The question therefore is how does the education system meet this demand? The graph in Figure 1.1 illustrates the typical annual supply of people into engineering.

GCSEs

Each year, there are around 650,000 students taking GCSEs – the first formal assessment in the education system across England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Scotland has a different qualifications system and while not presented here, the pattern of progression is similar. Of those students taking GCSE qualifications, around half will achieve good grades A*-C (or in the new grading system 9–4), which allows them to readily progress to some form of study towards engineering in their post-16 education, although many schools will require at least a B grade to continue studying mathematics and physics on an academic pathway.

Figure 1.1 Key transition points in engineering education skills supply

Due to the compulsory nature of GCSE qualifications, the cohort achieving good grades is fairly representative of the student population in terms of gender and ethnicity but is under-represented by those from lower socio-economic groups (SEEdash). Computing and Design & Technology, two other important enabling subjects, are not compulsory at Key Stage 4. These have participation of 65,000 and 165,000, respectively. There is increasing concern at the gender profile of the computing cohort with only 20% of young women choosing the subject at GCSE.

Post-16 education pathways

After GCSEs, there is a significant decrease in the skills supply to engineering as students are given their first opportunity to choose future subjects and pathways (academic or vocational/technical) of study.

‘A levels’ are the academic pathway for study after the age of 16 across schools in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland (with Scotland continuing its separate qualifications system). At A level, encouragingly mathematics is now the most pop...