![]()

1 A shift in architectural and urban design

Cities as a medium of change

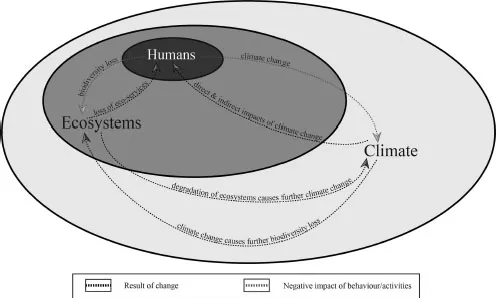

Humanity faces the dual challenge of climate change and degradation of ecosystems leading to biodiversity loss. Addressing such large problems, in terms of both scale and scope, needs many solutions to fit the vast variety of political, economic, cultural, climatic and ecological conditions within which humans dwell. Built environment strategies to effect change in human behaviour could be one such set of solutions. Because of the built environment’s role as driver of many of the causes of negative climate and biodiversity changes, because it is the primary habitat for humans, and because a focus on the built environment presents potential opportunities for change, this research focuses on cities as a medium for mitigating the causes of climate change. Specifically, how the built environment can adapt to climate change impacts while concurrently responding to the degradation of ecosystems and the loss of biodiversity through emulating or mimicking ecosystems themselves is investigated. Figure 1.1 illustrates that humans and their urban environments exist within ecosystems rather than as separate from them. Ecosystems in turn exist within and influence the greater global climatic system.

The causes of climate change and biodiversity loss are numerous, complex and interconnected, and stem largely from the way humans live in, understand and relate to the world around them. Estimates of how high the contribution to global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is from cities vary from 30% to as high as 80% (Spiegelhalter and Arch, 2010). Urban populations tend to be wealthier and consume more, although the proportion of urban dwellers that live in substandard housing1 worldwide is increasing from current estimates of 33% to projections of more than 40% by 2030. This represents approximately 25% of the total human population (Ezeh et al., 2017). Per capita carbon emissions are actually typically lower for people living within cities than their rural counterparts within the same country (Dodman, 2009).

Attempts to blame cities for climate change serve only to divert attention from the main drivers of GHG emissions – namely unsustainable consumption, especially in the world’s more affluent countries.

(Dodman, 2009, page 186)

Figure 1.1 Drivers and results of change

This means that although the built environment cannot alone be tasked with solving all of the identified issues, the way people inhabit the built environment does make a large contribution to the causes of both climate change and biodiversity loss. It is also therefore an important area where these problems may be addressed (McGranahan et al., 2005, page 821). Many technologies and established design techniques already exist that are able to mitigate or adapt to climate change, and work towards restoring the healthy functioning of ecosystems. Regarding just climate change for example, Lowe (2000) estimates that reductions of 80% in carbon emissions associated with the built environment are possible using current technologies. Similarly, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have stated that buildings offer more opportunities for cost-effective GHG mitigation than any other sector, although significant changes in current practice are required to achieve such an aim (IPCC, 2007a, page 59).

Cities offer unique opportunities for policy and governance changes leading to more tangible and immediate action to mitigate climate change. In fact, it is at the city level that most actions to either mitigate the causes of climate change or adapt to them are already occurring globally (Rosenzweig et al., 2010, Carter et al., 2015). This is because local authorities often have more direct control in many instances over emissions from cities through planning and land use policies, energy supply management, waste management, enforcement of industrial regulations and transport planning than central governments (Dodman, 2009). Urban environments in some instances achieve an economy of scale, meaning that access to capital is available, and that technologies or methods to mitigate climate change could potentially be more easily deployed. Furthermore, cities are well placed to act as centres of innovation and catalysts for social learning (Dixon, 2011). Several cities, including San Francisco, Portland, Philadelphia and Vancouver, which are located within countries that have recorded increases in GHG emissions, have actually reduced their emissions over the same periods,2 indicating that urban areas are more than capable of contributing to climate change mitigation even if located within a country that is unable or unwilling to engage in this.

The impacts of climate change and significant loss of biodiversity are occurring and will continue to occur despite any actions humans take collectively now (IPCC, 2007b, page 12, Rockström et al., 2009, Chapin et al., 2000, Gitay et al., 2002). This inevitable change is due to historic and current emissions of GHGs and disruption of ecosystems and species extinctions that have already occurred. Cities must then begin to adapt to climate change. Although the urban built environment occupies only approximately 3% of global land area, cities typically are the main sites of human economic, social and cultural life in terms of both magnitude and significance. More than half of all humans now live in urban built environments, a figure predicted to rise to 60% by 2030. People in developed nations spend upwards of 75% of their time indoors (Eigenbrod et al., 2011, Grimm et al., 2008). The built environment is also where nations and corporations invest large amounts of money and resources in terms of energy and materials. It is important then that the built environment remains a habitable place for humans. If the dominant economic philosophies and structures of human society and their resulting behaviours do not or cannot change in the short to medium term, it is doubtful that innovative or even conventional forms of design thinking and practice will alone be able to create significant change, before humanity is threatened or severely affected by the degradation of ecosystems and changes in climate (Turner, 2008).

There is a focus on both new and existing elements of urban environments in this book. New building and development projects provide substantial opportunities for initiating and demonstrating change, but most buildings that will exist when the effects of climate change become more acute have already been built in most urban centres. The existing built environment will need to be part of a long-term solution to climate change because buildings have relatively long lives and slow rates of renewal compared to consumer items such as cars or electronic equipment. An increased understanding of the problems associated with current methods of disposing of demolition waste may mean that buildings and their components are reused in greater rates in the future (Falk and Guy, 2007).

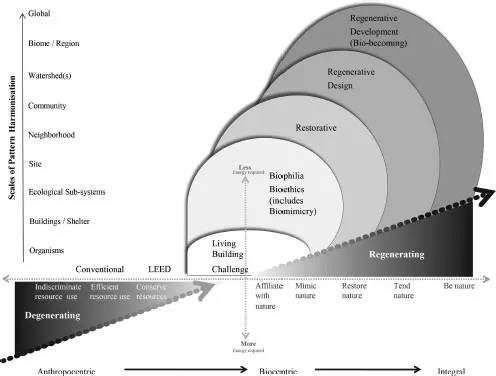

A synergistic response: ecological regeneration through urban design

Many current built environment climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies can be described as ‘sustainable’. This is an improvement on design that does not consider environmental impacts at all, however ‘sustainable’ design ultimately still tends to result in negative environmental impact (Reed, 2007). Through incremental steps the ultimate goal of such an approach is neutral environmental impact (Figure 1.2). Until this goal is reached, the built environment continues to degrade the ecosystems and climate humans are dependent upon for wellbeing, wealth, and basic survival. Under many current definitions sustainable design seeks to minimise pollution rather than achieve clean air, soil and water. It minimises energy use, rather than using energy from non-damaging renewable sources. It minimises waste, rather than eliminating it altogether by creating positive cycles of resource use. Within this paradigm, often no attempt is made to remediate past ecological damage. Most urban environments are built in such a way that the outcome is detrimental to climate, ecosystems and people (Newman, 2006), rather than nearing any state close to ‘sustainability’, even if just the original meaning of the term (‘to continue indefinitely’) is implied.

The goals of creating neutral environmental outcomes in terms of energy use, carbon emissions, waste generation and water consumption are ambitious and often difficult targets to meet in architectural and urban design. Given the urgency of the changes needed, and the severe outcome for humans should efforts not go far enough to reduce damage and prepare for changes, the built environment may need to urgently go beyond efforts to simply limit negative environmental outcomes. Instead, positive environmental outcomes should be the goal (Birkeland, 2008, Reed, 2007, Thomson and Newman, 2017, Girardet, 2015). This implies that the built environment should contribute more than it consumes to ecosystems while simultaneously remediating past and current environmental damage. Because it is not possible to replace the entire built environment, individual or small scale regenerative developments will have to cease, reduce, counter and reverse not only their own negative impacts but also those of existing buildings in a given urban environment.

Figure 1.2 Trajectory of regenerative design

Regenerative design

Regenerative design seeks to address the continued degradation of ecosystem services by designing and developing the built environment to restore the capacity of ecosystems to function at optimal health for the mutual benefit of both human and non-human life. Crucial to regenerative design is a systems-based approach. Buildings are not considered as individual objects but are designed to be parts of larger systems, and are considered as nodes in a system, much as organisms form part of an ecosystem. With a shift of this kind, complex and mutually beneficial interactions between the built environment, the living world and human inhabitants may more readily occur. Regenerative design is holistic in nature. The social or community aspects of a project are enmeshed with ecological health in terms of both physical and psychological wellbeing. For a development to become truly regenerative, the relationship between ecosystems and human society needs to be understood, utilised and nurtured to ensure maximum wellbeing for both. This book focuses mostly on the ecological aspect of regenerative design, rather than the social, psychological and aesthetic implications of such an approach to architectural or urban design. This is not because human wellbeing is thought to be separate from the positive benefits of ecological regeneration, or because the need to understand and develop positive relationships between humans and ecosystems is not absolutely essential, but is to narrow the scope of the research. The focus on the biological ecology side of design is not intended to negate the importance of the whole ecological-social systems understanding and holism that is central to regenerative design. The concepts discussed in this book are designed to add to and to complement parallel investigations into other aspects of regenerative design.3

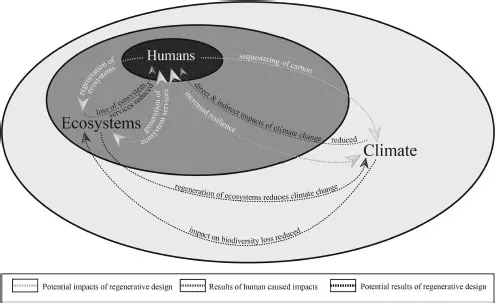

Figure 1.3 illustrates that if regenerative design strategies replace conventional ones in the built environment, human-caused biodiversity loss may be reduced4 if matched by changes in other aspects of human behaviour. At the same time, generation of additional ecosystem services may be provided either directly by the built environment or by integrating it effectively with ecosystems. Regenerative design works to reduce the causes of climate change through increasing biomass and thus potentially increasing the storage or sequestration of carbon. Cessation of the use of GHG-emitting energy sources as part of a regenerative development paradigm would also contribute to reducing the causes of climate change. This means the impacts of climate change would be reduced, particularly over the long term. Increasing the health of ecosystems increases their resilience as an adaptation response to climate change, and potentially also therefore means increased resilience in human urban environments that are strategically integrated into ecosystems (Gitay et al., 2002, Blaschke et al., 2017). An additional benefit of regenerative development is that increased ecosystem health may reduce some of the causes and ameliorate certain impacts of climate change, thus dampening the positive feedback loop between climate change and biodiversity described earlier (Figure 1.1).

A shift from a built environment that is degenerating ecosystems to one which restores local environments and regenerates capacity for ecosystems to thrive will not be a gradual process of improvements but will require fundamental rethinking of architectural and urban design (Cole, 2012). Even with such a change in design thinking, wide-scale change in human behaviours and consumption patterns would also need to be addressed. The practical task of how to create such built environments or enable them to evolve must be considered, particularly given the growing but still fairly scarce number of built examples that are able to reach even a ‘neutral’ status. The aim of this book is to describe a potential starting point for regenerative design in terms of ecological health, and to discuss how this could be used in an urban environment. It begins by investigating ecosystem services in general and then identifies potential key ecosystem services that are applicable to a built environment context. It examines how ecosystem services biomimicry might be applied to urban settings, and what benefits and difficulties are inherent in such an approach to design, or re-design of urban environments. The goal is to identify whether regenerative design is possible in urban settings, how to go about it, and to determine where key leverage points for system change may be within the built environment, in order to move towards a regenerative urban environment. A potential starting point for regenerative design in terms of ecological health is described and then tested.

Figure 1.3 Regenerative design impacts

Mimicking the living world

Some regenerative design literature implies that understanding organisms or ecosystems could be an important part of developing a regenerative design approach (Reed, 2007, du Plessis, 2012). This is because a...