![]()

Part I

History, media and regime

![]()

1 A short history of North Korea and kurimchaek

Origins

The question of how to identify the origins of comics is a matter of ongoing concern in comics studies. In the extensively cited work Understanding Comics (1994), Scott McCloud defines them as follows: ‘Juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer’ (p. 20).With this definition in place, he traces early examples of the medium back to ancient Egyptian tomb scenes, pre-Columbian picture manuscripts, the Bayeux tapestry murals and so forth. Other researchers, such as Thierry Smolderen, see the emergence of William Hogarth’s early- to mid-1700s engravings as ‘the defining moment when the prehistory of comics intersected with that of literature and the modern press’ (2014, p. 3). The emergence of the comics media in the late 1800s, with its intricate link to mass media and the press, is another point of departure. Here panels, speech balloons and sequential storytelling come together in the mass-circulated newspaper. Wertham, on his part, was preoccupied with the early 20th-century comic book as a modern, contemporary manifestation of capitalist interest, and as harmful mass media. There are similar debates on the formation of East Asian comics culture (Lent 2015). In Japan, formal aspects like panels, sequential images and drawing styles are traced to the Edo period (1603–1868) ukiyo-e woodblock prints and in particular to the sketches published by Hokusai from 1814 onwards (Berndt 2016).1 The Japanese comic strip evolved in late 19th-century cartoon magazines in close relation with The Japan Punch (1862–1887), a cartoon magazine created by Charles Wirgman for the foreign community (Okamoto 2001). Similarly, in Korea the development of newspapers and magazines during Japanese colonization (1910–1945) is often seen as a formative period of Korean comics culture, in the shape of newspaper cartoons and strips. This story is further complicated by ongoing, much wider scholarly, political and popular debates on the process of modernization on the Korean peninsula. A main preoccupation is to what extent social forces and processes were already engaged in this when the Japanese colonial powers took the hegemonic lead through a protectorate in 1905, and annexation in 1910 (Shin and Robinson 1999; Schmid 2002; Pai 2000).

The narrative of the history of the North Korean comics medium is arguably a nationalist variant of the second approach. In this version, North Korean print art, to which the comics medium belongs, emerged from Kim Il Sung’s struggle against colonial oppression. It aimed for the mobilization and enlightenment of the suppressed Korean nation. A New Turn in Print Art states: ‘The wall newspapers the Great Leader personally made became the models and prototypes of Juche-style print art, which directly and vividly show the agitational meaning and role of print art’ (2003, p. 33).2

Needless to say, other ways of locating the emergence of North Korean comics, and a critical approach to the domestic understanding, are possible. Non-North Korean scholarship argues that the discipline of history and even the understanding of social life in North Korea is inextricably linked with the life and history of Kim Il Sung. In North Korea: Beyond Charismatic Politics (2012), Korean anthropologists Heonik Kwon and Byung-Ho Chung note that:

In this historical art, political spirituality has a higher hand than commitment to empirical historical knowledge, and the value of creative work is judged on the basis of its capacity to perform a meaningful social function in the contemporaneous reality – that is, to raise the moral and political consciousness of the masses and to dedicate the wealth of honor to the polity’s exemplary center.

(p. 86)

While I provide critical perspectives on the North Korean nationalist historiography of print art and comics, the aim in this chapter is mainly to understand that historiography and its consequences, more than to supplant it. Post-1998 graphic novels must be understood in a social context in which this is the version of history available to publishers, writers, artists and readers.

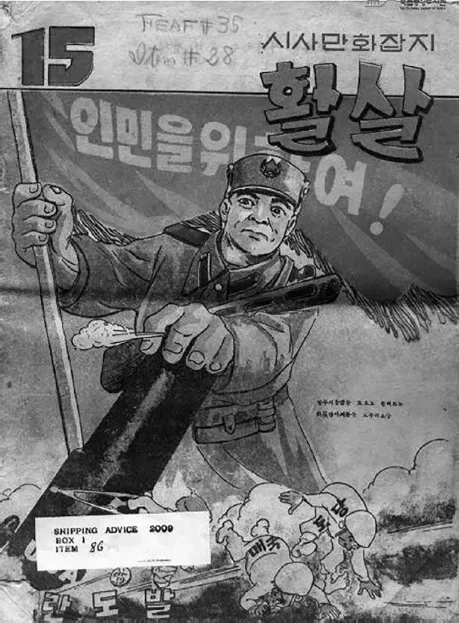

The earliest North Korean sources, which I have traced, are five volumes of the illustrated political satire magazine Hwalsal (The Arrow) from 1948–1950, and three volumes of the illustrated children’s magazine Children’s Kurimchaek: Our Comrade (Ŏrini kŭrimch’aek: uri tongmu) from 1949.3

Hwalsal is a 16-page illustrated magazine consisting primarily of satirical and agitating cartoons, comic strips and illustrated texts (Figure 1.1 Hwalsal, Vol.16 cover). Together, they mobilize their Korean readership to social revolution and criticize the Japanese, U.S. and South Korean enemies of the nation. The magazine mainly features various one-frame and full-page political cartoons, juxtaposing life in the North and South – the socialist and the imperialist-capitalist worlds. In many cases, this juxtaposition is accentuated by rendering self and other, right and wrong, in disparate graphic styles. Hwalsal volume 15 (pp. 6–7) and volume 16 (pp. 8–9) also contain multi-panel sequential image narratives on the merits of socialist, pro-North guerillas operating in the South.

While A New Turn in Print Art is preoccupied with the historical conflation of the comics medium and the agency of Kim Il Sung, the Leader is not a central character, social agent or theme in these volumes (see Chapter 3).4 Indeed, foreign influences and connections are explicit throughout the Hwalsal volumes; volume 9, p. 15, volume 15, p. 15 and volume 16, p. 15 all have editorial cartoons featured as ‘Soviet manhwa’. To readers familiar with North Korean history, this Soviet presence will not come as a surprise. Although the degree of Korean indigenous agency and influence in the formation of the northern Korean state and molding of socialist society is a point of debate in Korean studies, the dominant role played by Soviet occupational forces in state, society and the cultural scene is widely acknowledged.5

Figure 1.1 Hwalsal, Vol.16 cover

The Cold War significantly influenced comics produced in both North and South since the division of the country after liberation in August 1945. On both sides, writers and artists – often on state commission – have wielded the pen to criticize and satirize the enemy across the border. During the Korean War (1950–1953), both sides printed staggering amounts of propaganda pamphlets, posters and other visual materials. In the first year of the war, the frontlines shifted from North to South, South to North and then North to South again, only to solidify around the 38th parallel, where the war broke out. Artists, willingly or not, became part of the war machinery, some experiencing both propaganda departments as the opposing forces pushed both them and their readers back and forth across the ideological divide. South Korean scholar Paek Chŏngsuk argues that in this period war was not the only pervasive theme, however, as the comics medium in the South also emerged as a channel of unregulated entertainment that became associated with inferiority and delinquency (2013). Comics in the South were both popular entertainment and political instrument. The commercial aspect remains central, but throughout the history of the Republic of Korea they have also critiqued state power and mainstream society (Petersen 2012). By comparison, North Korean comics, seen both from A New Turn in Print Art and Hwalsal, evolved out of struggle, with a clear-cut definition of right and wrong. They narrate the nation and delineate state borders. Before sketching the trajectory of this narration and the social role of comics in the post-war period and up until 1998, a brief outline of the history of North Korea will be presented.

North Korea, 1948–1998

In North Korean historiography, the emergence and consolidation of the state is categorized into distinct periods:

- 1926–1945: The ‘anti-Japanese armed struggle’, also known as the ‘anti-Japanese revolutionary struggle’

- 1945–1950: The ‘period of peaceful construction’ or ‘democratic construction’

- 1950–1953: The ‘fatherland liberation war’ or ‘great national liberation’

- 1953–1958: The ‘struggle for post-war reconstruction and establishment of the socialist foundation’

- 1959–1966: The ‘struggle to advance the victory of socialism’

- From 1967: The period of ‘struggle to advance the victory of socialism’. (Lee Hyangjin 2004)

In North Korean historiography, during the ‘anti-Japanese revolutionary struggle’ the Korean people organized against the Japanese colonial oppressors and Korean collaborators within and outside the state borders to reclaim the lost nation. Kim Il Sung is described as the undisputed center of these activities. In this version of history, the emergence of the Korean nation in its current form is thus interconnected with Kim to the extent that 1912, the year of his birth, marks the beginning of the Juche era: the North Korean national calendar. Juche is also the name of the state ideology, and is translated as ‘subjectivity’, ‘self-reliance’ or ‘autonomy’. Recent non-North Korean scholarship does not challenge the notion of Kim Il Sung as a key individual in the nation’s trajectory. It has, however, demonstrated how North Korean history up until 1958 is also the story of how a leader successfully emerged from a continued series of struggles between various powerful factions that participated in the fight for independence and/or took part in the sharing of power in the northern part of Korea after Japanese surrender and liberation placed it under Soviet control. These factions included: a domestic faction consisting mainly of Southern communists who went North after Liberation in 1945; a Soviet-Korean faction that arrived with and were supported by Soviet authorities; a Yan’an faction consisting of veterans from the Chinese communist movement; and Christian nationalists with a strong powerbase in the North.

The period of peaceful construction saw Kim Il Sung, from the Manchurian faction, coming ...