![]()

p.1

Part I

Sacred earth and evil beings

![]()

p.3

1 In the beginning — was the wetland

In the beginning was the wetland. The earth and the water were without form and were chaotic, and darkness and light moved over the face and body of the earth and water. Earth and water were together one wet land. This was the first act of creation, the first coming into being, when the world was wetland, and the wetland was womb from which all later life sprung. Including human life. The wetland is not only the womb, but the womb is also a wet land, a slimy swamp of embryonic life. The wetland is not only the womb out of which all life came, but also the tomb into which all life dies and from which new life is (re)born. This was the world before the Fall, when the world was good and without evil, before the swamp and the marsh became places of darkness, disease and death, home alone to grotesque monsters lurking in the uncanny depths of their murky waters evoking horror and fascination in any who should have been unfortunate enough to stumble upon them.

Genesis

Is this rewriting of Genesis 1: 1–2 heresy or good theology? Or is it a bit of both? It is not a translation, nor a paraphrase of existing English translation, nor does it have a biblical basis or a traditional theological warrant. It is a rewriting of Genesis 1: 1–2 from a conservationist and environmentalist point of view. This is its only warrant (for an earlier discussion along these lines see Giblett, 1996, pp. 142–143). Genesis 1: 2 is translated into English in the official versions of the Bible as ‘the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep: and the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters’, or as ‘the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters’.

For Norman Habel in his ecological reading of the biblical creation story:

p.4

(Habel, 2000, pp. 36–37)

On Habel’s reading of Genesis 1: 2, wetlands and other waters are not places of darkness in a pejorative sense of being evil, sinister, or forbidding, nor are their waters threatening powers or turbulent forces of chaos. They are part of the benign dormant primordial order, but waters (and wetlands by implication) are not always and only benign. They are part of the dormant primordial slime. Waters can be threatening powers and turbulent forces of chaos. Westermann (1984, p. 105) comments that tehom ‘in the Old Testament has no other meaning than the deep or the waters of the deep. In can mean that which blesses or destroys just as can water’. Water is creative and destructive, life-giving and death-dealing.

Habel is indebted to Westermann when he embraces the first sentence in supporting his reading of tehom, but he does not accept the second one. Habel’s ecological reading of the biblical creation story projects ‘no negative verdict’ on darkness and waters, but this is not wise ecologically and culturally. His reading also demonstrates the difficulty of ascribing no values to darkness and waters, and to being neutral about both, for which Genesis 1: 2 seems to be striving, or to at least acknowledging that waters and darkness have a negative (but not evil) aspect. Westermann (1984, p. 104) also comments that chashak, translated as darkness, is ‘the opposite of creation. Darkness is not to be understood as a phenomenon of nature but rather as something sinister’, as threatening (and Habel seems to be alluding to, and repudiating, this interpretation) and as ‘the darkness of chaos’. Or, the chaos of darkness. On this reading, the darkness is certainly not evil, as evil has not been introduced into the creation and so the creation is good. On this reading also, the waters are not chaotic, but darkness is. Darkness is chaotic. Creation comes out of chaotic darkness, and not out of chaotic waters. When God divides land from water, He is not creating order out of chaos, but making dry land out of wet land, creating an amenable place for patriarchal pastoralism and agriculture to take place. He is also making a place suitable for cities, usually made of solid materials, to be located.

A decade later Habel (2011, p. 30) is more willing to embrace a reading of Genesis 1: 2 even more in line with my rewriting of it in wetland-friendly terms. The breath of God hovering over the primordial waters ‘suggests an image of parental nurture rather than primal disturbance’. Habel is also willing to locate himself ‘within the primordial habitat of Erets [earth] and identify with her as a character in the primal scene’. More precisely, she is obviously gendered as a feminine character and the mother is the usual provider of parental nurture, certainly exclusively with breast milk. Habel (2011, p. 30) goes on to comment that ‘the imagery of this habitat or scene suggests an embryonic figure without the form and fertility associated with the land mass called Erets. The scenario suggests a primal womb embracing the unborn Erets.’ Yet the landmass Erets is not, and can never be, an exclusively dry land mass. It is not fertile per se. When Erets assumes form and fertility, it is a wet land mass as well as a dry land one. The Erets is a land and water mass.

p.5

In a later section headed ‘The Birth Metaphor’ Habel comments further that:

(Habel, 2001, p. 31)

Yet Erets appeared on day one when God created the earth, and not on day three when God separated the land and waters. In the light of Habel’s earlier readings of tehom and the waters not as primal chaos, the implication of his reading is not that surprising.

What Habel does not address in his reading of Genesis 1 and in his repudiation of primal chaos and the old Chaoskampf reading of the biblical account of creation is that this older reading of the first book in the Bible is important culturally, especially for its associations with monsters and dragons. Habel, in particular, repudiates the connection of ‘tehom (deep)’ with ‘Tiamat, the chaos waters deity found in [. . .] Babylonian [. . .] myth’ (Habel, 2011, p. 29). More precisely, Tiamat in Babylonian myth is for Westermann (1984, pp. 29 and 31) ‘the primeval monster of chaos’ and ‘chaos’ is, or is interchangeable with, ‘a dragon’. John Milton in the seventeenth century did not repudiate the connection and was not successful in keeping the primeval monster of mythological Babylonian chaos at bay (as we will see shortly).

Irrespective of the biblical warrant for doing so, or for reading Genesis 1: 2 in terms of primal chaos, the association between the monstrous, the serpent, primal chaos, especially construed as their swampy habitat in hell, is a persistent trope in western European thinking and writing about creation, water and wetlands. When it comes to creation, water and wetlands, theological thinking and writing not only gets mixed up with Babylonian mythology, but also with Greek philosophy, in a syncretistic mélange (and John Milton’s Paradise Lost is also a case in point as we will see shortly after a brief excursion into a discussion of the four elements to provide the background).

Four elements

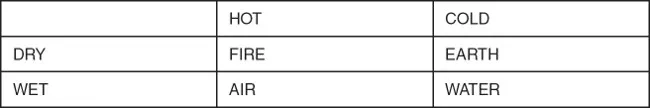

In European philosophy going back at least to Aristotle there are four elements: earth, air, fire and water.1 The four elements of earth, air, fire and water are combinations of the four primary qualities of hot, cold, wet and dry. According to this philosophy, water is the combination of the qualities of cold and wet; fire is the combination of the qualities of hot and dry; earth is the combination of the qualities of cold and dry; and air is the combination of the qualities of hot and wet, as shown in Figure 1.1.

p.6

Rather than being primary matter themselves, the first substances, the elements are products of primary qualities. Qualities on this view precede quantity; process precedes products.

Of course, in an age of global warming water can not only be wet and cold, but also wet and hot (and increasingly hot in the age of rising sea temperatures creating more frequent and intense hurricanes). Earth can not only be dry and cold, but also dry and hot (and increasingly hot in the age of more frequent and intense bush and forest fires). Air can not only be wet and hot (and increasingly hot with rising air temperatures and each year hotter than the last), but also dry and cold. But these are aberrant combinations according to the philosophy of the four elements. They are ruled out of the order of things based on a hard and fast distinction between the qualities and between the elements based on their proper combination of the primary qualities. Wet and hot air (and increasingly so), such as in the humid tropics and sub-tropics, and increasingly so in ‘Mediterranean’ and temperate climates, is generally regarded as uncomfortable. Cold and wet earth, such as in temperate wetlands, or hot and wet earth, such as in tropical and sub-tropical wetlands, or hot and dry earth everywhere else (and increasingly so) have been regarded as unacceptable.

Watery earth that mixes the two elements of earth and water has been regarded as aberrant, as dirt, as matter out of place, to use Mary Douglas’s terms (Douglas, 1966, p. 35). Wetlands have been considered as elemental aberrations, though these are creative and productive mixing of the elements in nature’s womb of mud (earth and water). Increasingly, elemental aberrations in the age of global warming are the new norm, though these are destructive mixings of the elements in culture’s tomb of crud (including mud). Increasingly in the age of global warming/climate change there is more and more dirt, more and more matter out of place, requiring bigger and bigger clean-up operations, costing more and more money. Thinking with the qualities and the elements helps to identify and sort through these different sorts of mixtures and aberrations with their intertwining of nature and culture, and to living with the earth in a better, more symbiotic way by, for a start, drastically reducing greenhouse gas emissions (dirty air).

Nature’s womb

John Milton’s Paradise Lost will suffice for the time being in this chapter as one case in point, as one proof text, of aberrant wetlands under the philosophy of the four elements. Reading Milton’s biblical epic poem ecocritically also provides an opportunity to rewrite ecocreatively some sections of Paradise Lost to showcase wetlands as a fertile mix of qualities and elements. Milton followed Aristotle in suit by only admitting the possibility of the mixture of four elementary qualities into what he called ‘the cumbrous elements, earth, flood, air, fire’ (III, 715):

p.7

[. . .] ye elements, the eldest birth

Of Nature’s womb, that in quaternion run

Perpetual circle, multiform, and mix

And nourish all things, let your ceaseless change

Vary to our great Maker still new praise.

(V, 180–184)

The mixing of qualities in ‘Nature’s womb’ to procreate the elements does indeed nourish all things as Milton indicates, but not only the four mixtures of qualities into the four elements that Aristotle and Milton permit. Indeed, the two aberrant mixtures of wet and dry, hot and cold produce the temperate and tropical wetland which are far more productive than both dry land and cold water. It is the wet land and warm water which give birth to life and which are the womb of the world.

Rather than the womb of the world, wetlands for Milton are the tomb in the underworld. In Paradise Lost Milton saw the Styx, one of the rivers of the classical underworld and for Dante a slimy swamp in the fifth circle of the Inferno (as we will see in a later chapter), as ‘the burning lake’, as ‘abhorrèd’ and as ‘the flood of deadly hate’ (II, 576, 577). In the same book of Paradise Lost he elaborates later in more detail on:

[. . .] lakes, fens, bogs, dens and shades of death,

A universe of death, which God by curse

Created evil, for evil only good,

Where all life dies, death lives, and Nature breeds,

Perverse, all monstrous, all prodigious things,

Abominable, inutterable, and worse

Than fables yet have feigned, or fear conceived,

Gorgons and Hydras, and Chimeras dire.

(II, 621–628)

This view of hell as swamp and swamp as hell persists through the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century, such as in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Dead Marshes in The Lord of the Rings (as we will see in the following chapter; see also Giblett, 1996, p. 140).

Milton’s pejorative theology of wetlands needs rewriting in environmentally friendly terms as places of both life and death:

Lakes, fens, bogs, dens and spirits of life,

A universe of life, which God by love

p.8

Created good, only for good, not evil

Where all life dies, new life lives, and Nature breeds,

Promiscuous, all maternal, all prodigious things,

Fascinating, horrifying, and better

Than fables yet have feigned, or fear conceived,

Marsh monsters, swamp serpents and dragons fiery.

These monstrous beings embody the mixing of the four elements of earth, air, fire and water (as we will see in later chapters, including in relation to Satan in Paradise Lost).

Later in the same book of Paradise Lost Milton describes in more detail the watery world and womb of the first day of creation that morphs into Hell:

[. . .] this wild abyss,

The womb of Nature and perhaps her grave,

Of neither sea, nor shore, nor air, nor fire,

But all these in their pregnant causes mixed

Confus’dly, and which thus must ever fight,

Unless th’ Almighty Maker them ordain

His dark materials to...