![]()

1 Introduction

Switzerland is well-known for its unique combination of three major political institutions: direct democracy, consociationalism, and federalism. In international comparison, albeit in the less recent literature,1 Swiss democracy has not only been considered as “the clearest prototype” (Lijphart 1999, p. 249) of a consensus democracy with extensive elements of power-sharing, but also an archetype of a federal state: Switzerland classifies as a “federation”,2 that is – following Watts (2008, p. 10):

[a] compound [polity], combining strong constituent units and a strong general government, each possessing powers delegated to it by the people through a constitution, and each empowered to deal directly with the citizens in the exercise of its legislative, administrative, and taxing powers, and each with major institutions directly elected by the citizens.

In fact, the cantons are among the most influential member states in relation to the central state (Vatter 2016).

A considerable number of English-language books have recently been published on Swiss democracy – some by political scientists or scholars in related fields (Lane 2001; Church 2004, 2016; Kriesi and Trechsel 2008; Linder 2010; Trampusch and Mach 2011; Tsachevsky 2014; Sciarini et al. 2015; Steinberg 2015), some by experts in constitutional law, thus following a more jurisprudential approach (Fleiner et al. 2005; Egli 2016; Haller 2016). While all of these offer important insights into the Swiss political system as a whole, they do not specifically concentrate on federalism, which at best is only presented as one aspect of the Swiss system.3 However, the fact that two comprehensive monographs on Swiss politics and the Swiss political system – the excellent books by Linder (2010) and Steinberg (2015) – have been printed in a third edition is a notable sign of the wide and continued interest in up-to-date, in-depth, detailed, competent, and comparative information on Switzerland. In fact, there is a steady stream of publications on Swiss politics. Such may point in the same direction as the bunch of literature that tries to present “Switzerland” as a “model” of various different things: of “political integration” (Deutsch 1976), more precisely of “European Integration” (Cottier 2013; Church and Dardanelli 2005) or even a “federal Europe” (Sap 2014; see de Rougemont 1965; Fischer 2014; Cheneval and Ferrín 2016), of the “principle of democracy” (Tsachevsky 2014), or of “solving nationality conflicts” (Schoch 2000; see Basta Fleiner and Fleiner 2000). If “the very Swiss model has become a benchmark case for analyses in comparative politics, political behaviour and multinational federalism” (Kriesi and Trechsel 2008: abstract), it may come as an even greater surprise that there is no single up-to-date English-language book that addresses federalism in Switzerland specifically4 – and this despite the fact that Switzerland is one of the oldest examples of a federal state as well as “one of the few examples of real federalism in the world” (Lane 2001, p. 7).5

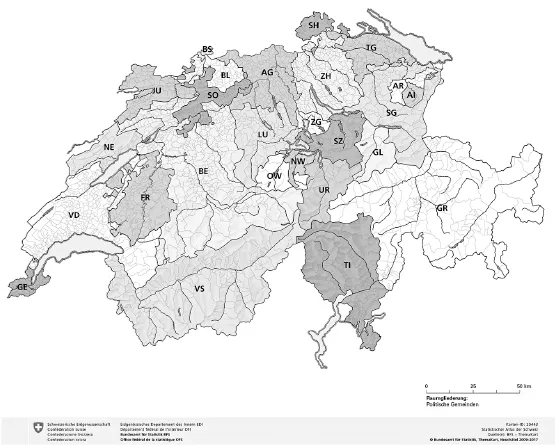

Figure 1.1 Modern Switzerland with its 26 cantons.

Source: Bundesamt für Statistik (2018).

In short, there is currently no English-language book available that provides an in-depth analysis of Swiss federalism as a key aspect of the Swiss political system, but at the same time remains accessible also to those not so familiar with either Switzerland or federalism. This volume aims to fill this gap. Therefore, the main and ambitious goal of this book is to offer a unique presentation of the Swiss federal system which includes sufficient basic information to serve as an introduction to graduate students, and the interested public, while simultaneously offering enough scientific analyses and up-to-date empirical findings to be interesting for more advanced scholars. In particular, this book will cover Swiss federalism in detail and discuss the substantial recent reforms, in particular the reform of National Fiscal Equalization and Task-Sharing between the Federation and the cantons (Neugestaltung des Finanzausgleichs und der Aufgabenteilung zwischen Bund und Kantone; NFA in short) that was accepted on 28 November 2004 by referendum and entered into force on 1 January 2008. Furthermore, this study will be of importance to the practitioner interested in how Swiss federalism has worked within its specific historical, cultural and political context, and in the lessons that can be learned from the Swiss experience not despite, but because of an understanding of its historical and institutional context. Finally, it will also be of interest to experts intrigued by (Swiss) federalism in both theoretical and empirical perspective.

The following quote by Ronald L. Watts (2008, p. 32), an eminent federalism scholar, may best illustrate that Switzerland is both a relevant and interesting case: “Although small in terms of population and area, its multilingual and multicultural character makes Switzerland’s federation of particular interest”.

This view is in accord with leading scholars in federalism studies (see Elazar 1994, p. 246; Dardanelli 2010, p. 142). But Swiss federalism is equally interesting for a wider community. Hence, Stein Rokkan (1970, p. V), one of the founding fathers of cleavage theory, considered Switzerland to be of special interest, calling the country “a microcosm of Europe” because of its cultural, linguistic, religious, and regional diversity. Once again, Rokkan (1970) is one of the numerous scholars who recommended that anyone trying to understand the dynamics of European politics should immerse themselves in the study of Switzerland and its federal system (see also de Rougemont 1965; Steiner 1994; Church and Dardanelli 2005; Cottier 2013; Fischer 2014; Sap 2014; Cheneval and Ferrín 2016). Rokkan’s (1970) advice is particularly relevant today given that the alleged political and economic crisis of EU integration has made it increasingly apparent how challenging it is to bring together different sovereign cultures, languages, and regions into a single system, thereby unifying “diversity” under a framework of “institutional unity”. Insights gained from the workings of the Swiss federation, namely the realization of an equilibrium between centrifugal and centripetal forces, unity and particularity, and between member polities and the central state, will help to tackle these challenges.

For all its potential usefulness as a model of one thing or another, and despite the fact that it has often been praised in the literature as one of the so-called “classic federations” (alongside the United States and Canada; see Elazar 1994, p. 246), Swiss federalism however, has only rarely been assessed in practice. As discussed above, very little has been written in English on the way the Swiss federal system actually functions, even though the literature consistently refers to Switzerland as a “unique case of ‘strong cantons in a strong federalism’” (Basta Fleiner 2003, p. 312), a prime example of a developed “bottom-up federalism”, and an “extreme case of federalism in international comparison” (Rentsch 2002, p. 403; see Bogdanor 1988, p. 69) – if not a “paradigmatic case” (Hueglin and Fenna 2015, p. 121). Some scholars even consider federalism as the central element of the Swiss political system, and in particular as the identity-giving political institution protecting their multicultural and plural society (Neidhart 2002, p. 124). Furthermore, international readers may be particularly unaware of the way in which federalism in Switzerland has changed in recent years, including reorganizations such as the complete revision of the Federal Constitution (1999) and especially the implementation of a new fiscal equalization scheme following the 2004/2008 reform of National Fiscal Equalization and Task-Sharing between the Federation and the cantons (NFA) which have transformed the Swiss federal system (Braun 2009; Mueller and Vatter 2016). Therefore, this book is an attempt to carefully describe and analyse the characteristics, institutions, and processes of Swiss federalism, along with its constitutive combination of stability and change, in order to make it accessible to a wider – that is an international – public. In doing so, the basic principles of Swiss federalism – i.e. the far-reaching autonomy of, and equality between the cantons, their rights to participate in the decision-making processes of the Federation, as well as their duty to cooperate – form the core thematic statement of the book. In sum, this monograph will introduce students and scholars alike to the origins, structure, operation, transformation, and significance of Swiss federalism.

Interest in Swiss federalism is further spurred by the marked increase in the constitutional design and practical use of federal arrangements in different regions of the world. In this, Burgess (2012, pp. 1–2) identifies the following countries as having become federal over the last two to three decades: Belgium (1993), Russia (1993), Ethiopia (1995), Bosnia and Herzegovina (1995), Nigeria (1999), Iraq (2006), and Nepal (2007); moreover, Grgić (2017) elaborates on the “asymmetric ethno federal structures” in the former Soviet and Yugoslav Regions (e.g. USSR and SFRY). In that sense, the present book will contain an up-to-date and exhaustive description of the structure, workings and reforms of Swiss federalism. For example, Germany tried, through a number of constitutional reforms, to change its federal architecture into a weaker form of intergovernmental collaboration (e.g. joint decision-making). However, although these reforms emerged as a serious attempt to overhaul and disentangle Germany’s federal system, the crucial element of fiscal federalism was deliberately excluded. Rather than succeeding in a comprehensive reform, the German Neuordnung der Finanzbeziehungen zwischen Bund und Ländern has not been achieved by June 2017 (Deutscher Bundestag 2017), which is some 10 years later since the last comprehensive reform of German federalism was up for discussion (Behnke 2010, pp. 40–41). Switzerland, facing similar, although weaker developments of joint decision-making at the end of the twentieth century, undertook a major constitutional reform of fiscal and vertical federalism between 1994 and 2008, so NFA. NFA envisaged not only a fundamental reallocation of competencies as well as a reconfiguration of the system of intergovernmental relations, but also a basic reform of fiscal flows. Although the intended effects of NFA have been confirmed by two public evaluation reports (as of 2010 and 2014), the political effects of NFA – that is, first and foremost, its effects on the cantonal political systems – are yet to be fully scrutinized (Arens et al. 2017). In short, NFA – as well as the complete revision of the Federal Constitution in 1999 – is a case of a successful federal reform at the constitutional level which might be of special interest for scholars and practitioners to understand the chances, but also the limitations, of constitutional change.

What is more, Switzerland and its recent changes raise a series of questions for broader research on federalism (see Watts 1998, 2008; Bednar 2011): How do federal systems achieve a balance between unity and diversity? How do they provide for the protection, integration, and participation of different cultural and regional minorities through federal arrangements? Under which conditions are federal reforms successful? While a number of recent articles, book chapters, and books have been written that address these questions through case studies, selected policy areas, or comparative analyses, there is no single volume that offers a systematic account of the Swiss federal system, introduces its subnational actors (i.e. cantons, municipalities), institutions, and processes, puts them into the wider societal and economic context, embeds them in the most recent research on comparative federalism, assesses its effects on the wider political system, and, at the same time, takes societal and political dynamics as well as their impact on the transformation of the federal system into account. There is, however, a shortfall: The book does not consider the manifold, yet unexplored EU’s impacts on Swiss federalism. Even 45 years after the country’s integration to the European framework was formalized for the first time (i.e. the 1972 Free Trade Agreement), still little is known systematically about possible consequences Europeanization may have for Switzerland’s core political institutions.6 Lack of research – especially if compared to the literature that addresses the EU’s impact on the regions of the member states (see Bache and Jones 2000; Tatham 2008, 2016; Donas and Beyers 2013) – may best be explained by the fact that there is no organized procedure of established the legal validity of EU rules in Switzerland (Schimmelfennig 2014, p. 256). Therefore, it is “up to the researcher to find out whether Swiss la...