- 330 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Homer

About this book

First Published in 1994. Part of a collection on Classical Heritage, this is a collection of Homer's influence from the Middle ages to the twentieth century. This series will present articles, some appearing for the first time, some for the first time in English, dealing with the major points of influence in literature and, where possible, music, painting, and the plastic arts, of the greatest of ancient writers. This volume includes essays on Chapman, Milton, Racine, Pope, neo-classical painter Angelica Kauffmann, Goethe, Keats, Gladstone and Tennyson, Tolstoy, Cavafy, Rilke, Joyce, Yourcenar, Kazantzakis, Seferis, East German poet Erich Arendt, and recent Nobel-prize winner Derek Walcott.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

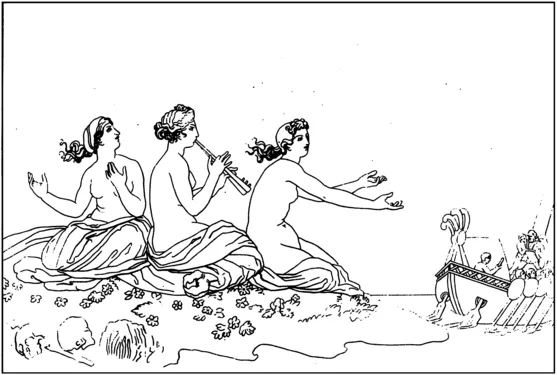

Figure 12. The Sirens. Flaxman (Odyssey series).

Kafka and the Sirens: Writing as Lethetic Reading

Clayton Koelb

Near the beginning of book 12 of the Odyssey, Circe gives Odysseus some famous advice:

Your next encounter will be with the Sirens, who bewitch everybody that approaches them. There is no homecoming for the man who draws near them unawares and hears the Sirens' voices; no welcome from his wife, no little children brightening at their father's return. For with the music of their song the Sirens cast their spell upon him, and they sit there in a meadow piled high with the mouldering skeletons of men, whose withered skin still hangs upon their bones. Drive your ship past the spot, and to prevent any of your crew from hearing, soften some beeswax and plug their ears with it. But if you wish to listen yourself, make them bind you hand and foot on board and stand you up by the step of the mast, with the rope's ends lashed to the mast itself. This will allow you to listen with enjoyment to the twin Sirens' voices. But if you start begging your men to release you, they must add to the bonds that already hold you fast.1

The hero carries out these instructions exactly, and he is able to experience the marvelous enchantment of the Sirens' song, to let himself in fact be overwhelmed by it, without having to suffer the terrible consequences that befell those who went before him: "The lovely voices came to me across the water, and my heart was filled with such a longing to listen that with nod and frown I signed to my men to set me free."2 Instead of setting him free, the men do as they have been instructed and tighten his bonds while the ship continues past the islands. Only when they are well out of earshot do they release their captain.

Franz Kafka wrote his own story based on this famous adventure, apparently in late October of 1917, but he never published it. Max Brod, Kafka's friend and literary executor, found it in one of the octavo notebooks Kafka had left and included it in a collection of fiction from Kafka's Nachlaβ which appeared in 1931. Kafka had not given it a title, and Brod evidently thinking to draw attention to the story's most surprising feature, called it "Das Schweigen der Sirenen" ("The Silence of the Sirens"). In Kafka's version, the Sirens indeed do not sing: "Now the Sirens have a still more fatal weapon than their song, namely their silence."3 This is the weapon that they use against the wily hero from Ithaca.

Kafka's Odysseus overcomes this formidable enemy, however, because he "did not hear their silence."4 In Kafka's story of the encounter with the Sirens, not only had Odysseus had himself bound to the mast, but he, too, has stopped his ears with wax, as the second sentence of the narration tells us: "To protect himself from the Sirens Ulysses stopped his ears with wax; and had himself bound to the mast of his ship."5 This alteration of Homer's story, this wax in Odysseus's ears, is, I contend, a far more significant change than the substitution of silence for singing. It is possible to write a story about the Sirens' silence that is on the whole faithful to the spirit of the Homeric original and can be read as a version of the adventure from the Odys- sey. As soon as you put wax in Odysseus's ears however, you leave the Odyssey completely, you forget it, as it were, and embark on a different narrative project altogether.

Homer's story has two essential features. First, it tells how the Greek sailors were able to pass the island of the Sirens without falling victim to the deadly song, and, second but equally important, it explains how Odysseus was able to accomplish the feat of both hearing the Sirens and escaping them. This section of the Odyssey, we remember, is not narrated directly by the poet but is part of a long quoted discourse by Odysseus to the Phaeacian king Alcinous and his court. The story of the Sirens is therefore part of a first-person narrative embedded in the poem, where the point of view belongs exclusively to the hero. He can tell us only what he has experienced. Odysseus is able to recount to the Phaeacians exactly what the Sirens sang to him as his ship passed and to make their song a part of his story only because he heard it himself. Odysseus's unstopped ears are an essential feature of the tale, then, not only because of what is revealed about the hero's character but also because they are the absolute narrative prerequisite of the story.

Odysseus plays the role of witness. If the story does nothing else, it establishes him as the single mortal authority on the Sirens. He alone among living men knows what the Sirens sing and what effect their song has. The central section of the Odyssey, wherein the most fantastic of the tales are related, depends entirely upon the witness role of the hero and is in a sense about nothing so much as this role. The poet does not ask us to believe him; he gives us an eyewitness whose stature within the fiction is such that it encourages, though it does not guarantee, belief. Everything we know about the Sirens comes from Odysseus; we must either accept what he says or reject it and, if we reject it, reject along with it a substantial portion of the entire poem.

The most fundamental feature of the Homeric version of the tale, then, is the unique authority it ascribes to the narrating voice of Odysseus himself. One could change various elements of the story and still be true to the basic Homeric structure, so long as Odysseus himself retains his position as unique witness. One could even change the Sirens' song into silence and still remain within the basic tradition established by Homer, as long as it was Odysseus himself who testified to their silence. This is exactly what Rilke did in the poem "Die Insel der Sirenen" ("The Island of the Sirens"), written one decade before Kafka's story, in 1907:

Wenn er denen, die ihm gastlich waren,

spät, nach ihrem Tage noch, da sie

fragten nach den Fahrten und Gefahren

still berichtete: er wußte nie,

wie sie schrecken und mit welchem jäheo

Wort sie wenden, daß sie so wie er

in dem blau gestiliten Inselmeer

die Vergoldung jener Inseln sähen,

deren Anblick macbt, daß die Gefahr

umschlägt; denn nun ist sie nicht im Tosen

und im Wüten, wo sie immer war.

Lautlos kommt sie über die Matrosen,

welche wissen, daß es dort auf jenen

goldnen Inseln manchmal singt—,

und sich blindlings in die Ruder lehnen,

wie umringt

von der Stille, die die gauze Weite

in sich hat und an die Ohren weht,

so als wäe ihre andre Seite

der Gesang, dem keiner widersteht.6

spät, nach ihrem Tage noch, da sie

fragten nach den Fahrten und Gefahren

still berichtete: er wußte nie,

wie sie schrecken und mit welchem jäheo

Wort sie wenden, daß sie so wie er

in dem blau gestiliten Inselmeer

die Vergoldung jener Inseln sähen,

deren Anblick macbt, daß die Gefahr

umschlägt; denn nun ist sie nicht im Tosen

und im Wüten, wo sie immer war.

Lautlos kommt sie über die Matrosen,

welche wissen, daß es dort auf jenen

goldnen Inseln manchmal singt—,

und sich blindlings in die Ruder lehnen,

wie umringt

von der Stille, die die gauze Weite

in sich hat und an die Ohren weht,

so als wäe ihre andre Seite

der Gesang, dem keiner widersteht.6

Although Rilke revises the Homeric account in a surprising way here, he remains faithful to the basic structure of the classical version. The danger is still the Sirens' song, but now that song is perceived only indirectly: the sailors know that singing is sometimes heard coming from these islands, and the expectation of song conditions their experience of silence so that it is transformed into "the other side" of an irresistible singing. More important than this, though, is Rilke's reliance on Odysseus as the reliable witness. It is through Odysseus that the reader learns about the island of the Sirens and about the silence that is the other side of song. Like the story from the ancient epic, Rilke's poem focuses as much on the situation of the telling as on the story itself. The first stanza, for example, has nothing at all to do with the Sirens but rather is taken up with setting the scene of Odysseus's report, with explaining why and how he delivered himself of it. One might even suspect that the poem is meant to be as much about the storyteller himself as about the matter of his story. This suspicion is confirmed when we notice that the word still is used to describe how the hero "reported" (berichtete), the very same lexeme that appears later in substantive form (Stille) to describe wherein lies the danger of the islands. Odysseus's "song" is thus no different from whatever it is that emanates from the island of the Sirens. It is a form of "quiet" that contains vast spaces ("die die ganze Weite in sich hat") and that may be as dangerous to the hospitable (gastlich) Phaeacians as any tales full of "Tosen und Wüten" (ranting and raving).

Rilke's poem essentially uses the authority of the Homeric text to authorize the alterations it makes in that text. We are not asked to take the word of some unknown, faceless narrator that the Sirens did not actually sing: Odysseus himself, whom Homer has told us was actually there and actually heard whatever it was that came from that island, Odysseus the eyewitness, revises the story. Rilke remains well within the main current of the tradition, even while he questions one of the prominent features of the tradition, because he accepts the fundamental structure of the Homeric narrative situation. One could even say that Rilke basically accepts the central point of the classical story by retaining Odysseus as narrator and sole medium through which we learn what it was the Sirens did; for that central point is not that the Sirens sang this or that song or that they sang at all but that, whatever it was they did, Odysseus was able to observe it and yet come away alive.

For these reasons, then, I would call Rilke's poem an alethetic reading of the Homeric story. An alethetic reading, as I have detailed elsewhere,7 is one that assumes that the text being read essentially tells the truth, no matter how incredible or full of error that text may appear to be. Such reading assumes that texts have an outside and an inside, or a surface and a depth, and that an incredible surface can be opened up to disclose a depth worthy of belief. Rilke's "Die Insel der Sirenen" reads the Odyssey alethetically in that it assumes that the basic import of the epic is true and correct, even if its surface has been distorted by the replacement of an "actual" silence (as the revision would have it) with the imagined song which is its "other side." Homer's story of the Sirens matches Rilke's version if it is read as a certain kind of allegory wherein the song that Odysseus reports hearing is understood as the mythic fleshing out of the vast space (Weite) encompassed by the mysterious silence. In this reading, the words that Odysseus ascribes to the Sirens—words full of flattery ("flower of Achaean chivalry") and promises ("we have foreknowledge of all that is going to happen")8—are his own desires projected into the emptiness around him. There is no incompatibility between Rilke's and Homer's accounts as long as we presume that texts do not always say directly what they mean, a presumption fundamental to all alethetic reading.9

When we turn to Kafka's story, however, we are faced with a radically different situation. The narrator is no longer Odysseus himself but instead a nameless and characterless voice whose chief claim to authority is his knowledge of tradition, but now a tradition in which Odysseus has no role as witness. This narrator knows things that Odysseus does not and cannot know, including the potential meaning or meanings of the adventure. Odysseus's role as witness is erased from the outset with the announcement that he not only bound himself to the mast but stopped his ears with wax as well. With that announcement the story detaches itself completely from the tradition and sets off on a course entirely its own.

Kafka's "The Silence of the Sirens" is therefore a "lethetic" (that is, forgetful or oblivious) reading of the epic tale.10 Lethetic reading takes place when the reader acts as if he or she does not believe the text being read and thus deliberately ignores what the text seems to be trying to say. It is not a naive misunderstanding but an intentional radical reshaping of the materials out of which the text is made; it assumes, in fact, that the text being read is ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- SERIES PREFACE

- PREFACE

- INTRODUCTION

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- CONTRIBUTORS

- THE MIDDLE AGES AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE

- ENGLISH RENAISSANCE

- SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

- EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- NINETEENTH CENTURY

- TWENTIETH CENTURY

- Select Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Homer by Katherine Callen King in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Modern Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.