![]()

1 The aesthetics of the early modern grotto and the advent of an empirical nature1

Luis Rodríguez Rincón

Of the diversity of imaginative aquatic spaces that Gaston Bachelard and Margaret Cohen describe – from fresh to salt water, calm to stormy seas, open oceans versus shorelines – grottos are a little-theorized and historically contingent category.2 Grottos were a pagan architectural topos that was widely adopted in European architecture and literature starting in the fifteenth century. What complicates any modern assessment of the early modern grotto is the need to suspend divisions that today maintain the study of art separate from the study of nature. In fact, the grotto’s flourishing is a testament to the productive energies unleashed by the convergence of pagan aesthetics with natural history in the early modern period. What, then, was a grotto? Why did early modern potentates across Europe invest vast sums to build this pagan architectural topos?3

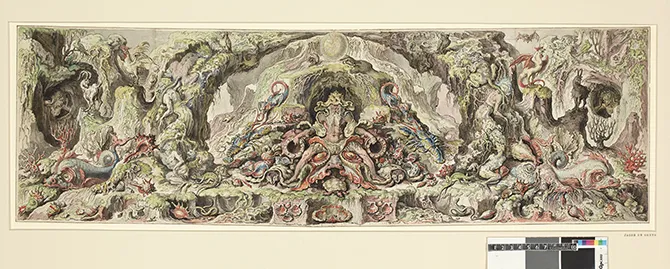

In the sixteenth century, whenever a character was led beneath a body of water they undoubtedly entered a grotto.4 As representations of what lay below the surface, of what linked oceans to terrestrial sources of water, grottos like the one designed by the Dutch artist Jacques de Gheyn II (1565–1629) were artificial caves showcasing marvels of hydraulic engineering alongside collections of classical artwork and natural specimens. The closest homologue today in terms of meaning and prestige to the grotto would not be the pleasure caves of the rich and famous but rather the modern museum.5 De Gheyn’s grotto (Figure 1.1, see plate section), built in the 1620s for Prince Maurice of Orange-Nassau (1567–1625) at his palace in The Hague, was the Netherlands’ first.6 No doubt inspired by the botanical gardens at the University of Leiden, which de Gheyn drew in 1600, his grotto showcased an expensive array of shells, coral, and sea life and was part of a larger plan for a garden of exotic plants and an aviary.7

Plate 1: Figure 1.1 Jacques de Gheyn II, Design for a Garden Grotto, c. 1620-5, paper, 22.8 x 74.2 cm. Courtesy of the British Museum.

What baffles modern viewers in this grotto is the co-existence of the empirical with the fantastic in de Gheyn’s design. As Claudia Swan argues, de Gheyn’s oeuvre straddles the divide between two very different eras of Dutch art: “His is an oeuvre committed equally to the naturalistic representation of the world as it appears and a world of spectral fantasies.”8 In his grotto, naturalistic renderings of real animals and shells appear alongside hybrid creatures that conflate the terrestrial with the oceanic, the organic with the inorganic, and the human with the non-human. The grotto is symmetrical along a vertical axis demarcated by a human figure typically identified as Neptune. He sits encased in billowing shells that merge his humanoid body with the landscape it ostensibly controls. For Felice Stampfle, Neptune’s metamorphic dismemberment can be traced directly back to the grotesque style of ornamentation adopted in early modern Europe from rediscovered Roman murals.9 Neptune’s material encasement suggests a sentience to the aesthetics of this underwater realm underscored by the monstrous visage of his throne that emerges like a double-image from between the sea god’s legs. The whole landscape seems capable of returning the viewer’s gaze. One is rightfully left searching for the line dividing nature from art in a space predicated on the very erasure of such a distinction as the artist demonstrates nature’s truth as aesthetics.

Such was the grotto as a submarine microcosm distilled from the interpretation of a pagan topos. While grottos share a distinctive rustic aesthetic that imitated the look and feel of natural forms, it was one that resisted the modern notion of aesthetics. That is, the idea of beauty for its own sake, of surfaces without hermeneutic depths. Rather, the revival of the grotto in the renaissance and its evolution as the sixteenth gave way to the seventeenth century serves as a testament to the productive, though idiosyncratic, early modern linkage of the study of nature to hermeneutics, aesthetics to meaning, and antiquity to the natural world. In sum, the grotto’s evolution in the sixteenth century links the early modern advent of an empirical science of nature to a fascination with pagan art.

The conceptual genealogy of the renaissance grotto harkens back to the Greco-Roman practice of the museum in its original etymology as a shrine to the Muses, patron deities of the arts. The ancient Greek practice of designating natural caves and springs as divine spaces was one point of origin for this tradition.10 Over time such natural, sacred caves came to include artificial components. The construction of artificial grottos that mimicked the features of natural springs spread to Rome by the 1st century BCE, becoming popular with both citizens and emperors alike.11 With the transition from Roman to medieval times, new grottos stopped being built while old ones fell into ruin or disappeared, leaving a heterogeneous heritage of scattered ruins and textual fragments that to this day reads opaquely. Renaissance grottos appropriated and misinterpreted this pagan tradition by drawing inspiration from a slew of different pagan structures: some religious, some profane, intended for public display, or private enjoyment. Even today, what might be translated as grotto conflates different classical structures, whether they be temples, fountains, or baths.12

The renaissance revival of the grotto begins in fifteenth-century Italy. The famed Italian polymath Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72) provides the earliest and perhaps most influential early modern description. In his De re aedificatoria, published posthumously in 1485, Alberti set the parameters for the design and aesthetic of the grotto for the next century:

To their grottoes [antris] and caves [criptis] the ancients used to apply a deliberately roughened revetment of tiny pumice chips, or Travertine foam, which Ovid called ‘living pumice.’ We have also seen green ocher used to imitate the bearded moss of a grotto. Something we once saw in a grotto gave great delight: where a rushing spring gushed out, the surface had been made up of various seashells and oysters, some inverted, others open, charmingly arranged according to their different colors.13

What delighted Alberti was the “deliberate” fabrication of an “imitated” nature through the revival of Greco-Roman architectural practices. Delight for Alberti was produced both through the imitation of natural colors and surfaces and through the symmetrical arrangement of shells to produce mosaics that outdid nature’s beauty. This was a space of revelation where shells represented the treasures of a submarine world whose empirical reality fascinated curious minds. Alberti’s interest in techniques that make nature into a pagan aesthetic practice illustrates a paradox of late medieval and early modern thought: that the interpretation of pagan art animated the study of nature.14

The grotto’s rustic aesthetic was inseparable from a pedagogical imperative that did not value pagan art and natural beauty for its own sake. Rather, the function of aesthetic delight was to educate an audience by engaging the senses in order to elevate the mind. Alberti’s description of a grotto is situated in the section of his treatise where he codified the architectural parameters of the Renaissance villa upon a pagan model.15 His architectural precepts went hand in hand with his appraisal of a lifestyle based on otium.16 For renaissance intellectuals like Alberti, civilized life was bifurcated between negotium, the business characteristic of city life, and otium, which celebrated a leisurely rural life dedicated to intellectual pursuits and moral edification. Immediately preceding Alberti’s description of the grotto is a list of other delightful ornaments appropriate for the country villa:

We are particularly delighted when we see paintings of pleasant landscapes or harbors, scenes of fishing, hunting, bathing, or country sports, and flowery and leafy views. It is worth mentioning the emperor Octavian, who collected rare and enormous bones of huge animals as an ornament to his house.17

Key to the aristocratic ideal of otium was a mixing of delight with an investment of time and money into intellectual pursuits like building, collecting, and studying.18 Take for example the Marchesa of Mantua Isabella d’Este’s (1474–1539) grotto, built by 1508, where “adjacent to Isabella’s studiolo, the small anticamara of the grotto served as a museum providing a combination of studium and otium … adorned with allegorical paintings.”19 Intended as a space of respite and reflection, the grotto was from its Italianate beginnings associated with collecting classical objects and natural curiosities for study and admiration: “with its massing of curiosities and precious stones and in its cramped quality, the grotto overlapped with the later Wunderkammer.”20 This holds true for the first grottos built around the Papal Court, which displayed the growing collection of Greco-Roman statuary in a rustic garden setting. Donato Bramante (1444–1514), the architect who designed the Belvedere Courtyard at the Vatican, with its fountain-niches built to display the recently rediscovered Roman statues of the Nile and Tiber, was also responsible for designing a nymphaeum built in 1508–11 for Cardinal Pompeo Colonna in Genazzano.21

The pedagogical imperative implicit in renaissance no...