- 210 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In The Tank Debate, John Stone highlights the equivocal position that armour has traditionally occupied in Anglo-American thought, and explains why - despite frequent predictions to the contrary - the tank has remained an important instrument of war. This book provides a timely and provocative study of the tank's developmental history, against the changing background of Anglo-American military thought.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Tank Debate by John Stone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION: EXPLAINING THE TANK DEBATE

From recent comments, I wonder sometimes if I am presiding over a fleet of dated dinosaurs or am like the Flag Officer Battleships of 1939, who must have believed that he controlled the most important and unchallenged element in the defence of the United Kingdom and of the Empire.

Thus spoke Major-General J.M. Brockbank, Director of the Royal Armoured Corps—and a decidedly beleaguered figure in March 1974.1 Just six months previously, the opening stages of the October War in the Middle East had witnessed the first large-scale use of operator-guided anti-tank missiles. Such weapons were not in themselves new, but the startling losses inflicted by the Egyptian infantry on unprepared Israeli armoured formations had understandably led to widespread concern over the future of the tank. Back in Britain, Brockbank created a plausible case—framed in technical and tactical terms—for the continuing utility of heavy armour. Had he chosen to adopt a more historical perspective on the subject, he might also have drawn comfort from the fact that this was not the first time that the tank’s demise had been widely predicted. Indeed, since its introduction in 1916 it has endured what can only be described as a highly equivocal status in both Britain and the United States. At times the tank has occupied an important—even dominant—position in Anglo-American military thought, while at other times it has suffered from more than its fair share of detractors.

This cycle of acceptance and rejection (underpinned by the tank’s stubborn refusal to disappear) has not escaped attention. In 1960 Liddell Hart observed that

[t]ime after time during the past forty years the highest defence authorities have announced that the tank is dead or dying. Each time it has risen from the grave to which they have consigned it….

He continues by providing five specific examples of such ‘death-sentences’ drawn from the interwar period and the Second World War.2 Some years later Richard Simpkin made essentially the same comment.

The tank has more lives than the proverbial cat—and needs them. Politicians, scientists and the media have been performing its obsequies every 5 years or so since the twenties.3

Richard Ogorkiewicz has likewise drawn attention to the regularity with which the tank’s demise has been predicted, and has periodically felt it necessary to argue for the continuing value of heavy armour on the modern battlefield.4 Finally, Ulrich Albrecht has also highlighted this feature of the tank’s developmental history, and has updated Liddell Hart’s collection of ‘death-sentences’.5

The phenomenon of claim and counter-claim—which I term the ‘tank debate’—has in fact been a defining feature of the Anglo-American attitude to armour since the First World War. As we will see shortly, in no other country has the tank retained such an uncertain position over such a prolonged period of time. Indeed the sheer degree of equivocation makes it surprising that no serious attempt has yet been made to expose its origins, for in doing so we might expect to discover something of intrinsic historical interest, and also identify those errors of thought that have to date produced so many inaccurate assessments of the tank’s potential. This book, then, represents the fruits of my own efforts to do just this: to identify those frames of reference which have traditionally underpinned the Anglo-American tank debate, and to show how they have contributed to the debate’s chronic nature.6 Predictably enough, I have also yielded to the temptation to make some observations of my own about the future of the tank, and—ironically—the conclusions which I have drawn differ very little in their essentials from those of so many previous writers on this subject. In fact it is my contention that the previous ten years or so have witnessed a steady decline in the operational utility of the main battle tank to barely adequate levels, and that the longer it remains in service the more marginal will its utility become. But if this sounds very much like the kind of assertion that has dogged the tank over the past eighty years, I should point out that my underlying reasoning differs in certain significant ways from previous thinking on this issue, and I do not believe that I am ‘re-inventing the wheel’ in this respect. Before we go into further detail on this point, however, some preliminaries are in order, the first of which is to clarify my use of the word ‘tank’ which might conceivably encompass a broad range of armoured fighting vehicles.

THE MAIN BATTLE TANK

The focus of this book is the main battle tank of the kind which presently constitutes the core of British and US armoured formations. By the later stages of the Second World War both countries were organising their armoured divisions around a single model of medium/cruiser tank—the M-4 Sherman. Nevertheless, the main battle tank (or, more simply, battle tank) is properly a postwar concept, although the first generation did grow out of two wartime designs: Centurion and the M-26. During the immediate postwar years, developed models of these two tanks comprised the backbone of Western armoured divisions, supported by a smaller number of light tanks and other armoured vehicles designed for reconnaissance, along with heavy-gun tanks designed to provide long-range firepower against particularly tough targets (principally the Soviet JS III heavy tank). Light tanks subsequently retained some utility, but the heavy-gun tank soon languished in the face of postwar developments in gun-ammunition systems. More specifically, the considerable increase in firepower, which was achieved with the introduction of the British L7 105-mm gun and sabot round, obviated the need for a dedicated heavy-gun tank, and as a result there were no direct successors to the British Conqueror and the American M-106. Instead, the idea of the battle tank emerged as the most powerfully armed and best-protected weapon system on the battlefield.

As its name suggests, the battle tank is designed to operate in the demanding conditions associated with a major engagement on the modern battlefield and, more specifically, to be capable of prevailing in the face of enemy armour. The performance demands that this latter requirement imposes have resulted in a considerable degree of role specialisation. This is most clearly manifested in successive generations of British armour (Centurion, Chieftain and Challenger) which have all ‘pushed the envelope’ in terms of firepower and protection. Until the 1970s US design policy was somewhat less insistent in this respect, but the XM-1 programme marked a turning point and signalled a more serious intention to achieve superiority in those areas of performance which are most important for battlefield success. Thus during the 1980s the British and US armies acquired in Challenger and the M-l Abrams a new generation of tanks, which were first and foremost highly specialised killers of their own kind.

Although the concept of the battle tank grew to fruition during the postwar years, its general physical configuration emerged rather earlier, during the middle phase of the Second World War. By this stage various combinations of multiple turrets, bow guns and sponsons had given way to a single, fully rotating turret mounting the main armament and a co-axial machine gun. The turret also housed three crewmembers—commander, gunner and loader—while stations were provided in the main body of the tank for two others: the driver, and the radio operator who also operated a second, bow-mounted machine gun. The Allies achieved this configuration with Sherman in late 1942, and stayed with it for Centurion and the M-26. Postwar designs have dispensed with the fifth crew-member and the bow machine gun, thereby saving on internal volume and eliminating a weak spot on the frontal armour, which can also now be more radically sloped. Nevertheless, the ‘twin-level’ hull/turret arrangement has remained a consistent feature of almost all national design policies. Only in Sweden has there been a departure from this approach in the form of the ‘S’-tank (Strv. 103) with its fixed, hull-mounted gun.7 The correspondingly low silhouette which results from this configuration confers benefits in terms of tank survivability (harder to see and hit), but only at the cost of foregoing certain other tactical advantages. A fully traversing turret, for example, generally permits much more flexibility in the employment of armoured vehicles, and now provides an even greater advantage over a fixed gun given the ability of modern tanks to fire accurately on the move. Less obviously, perhaps, the conventional configuration also endows a tank commander with a very useful degree of what is termed ‘top vision’. Since his head is more or less level with the turret roof he effectively retains an all-round field of view, and he is also unlikely to be observed over intervening terrain by anything which he cannot himself see. Lack of top vision is also one of several problems associated with various tank prototypes sporting innovations such as pedestal-mounted guns, which might otherwise provide the tactical flexibility associated with a conventional turret but at a considerable saving in weight.8

All in all, therefore, it is hardly surprising that design closure was achieved with the turreted tank. This particular arrangement—which might be termed the conventional configuration—appears to embody an optimum compromise in relation to the various factors which determine battlefield performance, and as such it has undoubtedly played an important part in making the tank into the highly capable weapon system that it is still perceived to be today. Indeed, it is exactly this time-proven record of success which makes it so surprising that concern over the tank’s future has rarely been far from the surface of the Anglo-American military consciousness. Thus we are back to our original question—namely how can we account for the persistence of the tank debate?

EXPLAINING THE TANK DEBATE

The long-running nature of the tank debate may have attracted considerable comment from various sources, but the more limited number of attempts which have been made to explain the phenomenon remain unconvincing. This is largely because of their overly narrow focus on technological issues—an approach which is exemplified by Richard Ogorkiewicz’s observation that periodic doubts about the tank are the result of significant developments in anti-tank systems. During the interwar period, he argues, the anti-tank gun was seen as the primary threat; the Second World War added the problem of Bazooka-type weapons and rocket-firing aircraft, while in the postwar period precision-guided munitions have intermittently caused considerable concern.9 Clearly there is something of value in this explanation, as a tank which is no longer adequately protected against specialised attack becomes vulnerable, and confidence in its utility drops accordingly. To take just one example here, the relative decline in the M-4 Sherman’s firepower and protection which occurred during the final years of the Second World War was an important factor in explaining subsequent Allied misgivings about the future of the tank.

Nevertheless, explanations which rely too heavily on this kind of technological reductionism cannot be considered wholly satisfactory. They fail, for example, to account for the peculiar resilience of the idea that developments in anti-tank weapons constitute a threat to the future of armour, when all experience suggests that countervailing developments in tank design can be expected to redress the situation. As Liddell Hart observed, shortly after the Second World War, any claim that

the tank has met its master in the anti-tank projectile … would be more convincing if it had not been so often repeated, and as often refuted by experience.10

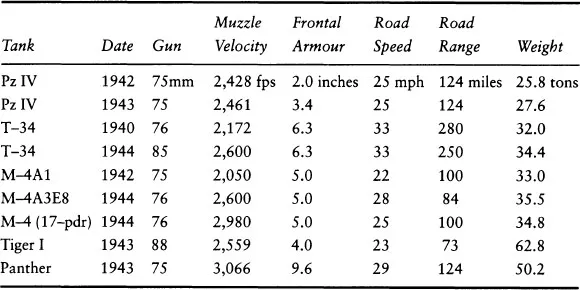

Equally importantly, our reductionist explanation cannot wholly accommodate the marked disparity between Anglo-American views on the nature of the technical threat to armour and the more sanguine attitudes of other major tank-using nations such as Russia and Israel, whose opinions will be examined shortly. Such differences can in part be explained by the inferior quality of British and American armour during the Second World War, although it is possible to exaggerate the advantages enjoyed by the Germans and Soviets in this respect. For example, a comparison of Sherman’s characteristics with those of the other two most numerous medium tanks of the period (the Soviet T-34 and the German Mark IV) reveals no overwhelming performance gap (see Figure 1.1). In contrast, the German Panther and Tiger did enjoy a significant advantage over Sherman in terms of firepower and protection, and they constituted an increasing proportion of German tank strength in north-west Europe during 1944–45.11 Moreover, German tactical virtuosity, along with the natural advantages accruing to the defender, also made life hard for Allied tank crews in Europe. But when these elements were not present—as at Kursk (1943) for example—life could be equally unpleasant for their German counterparts, and yet nobody, I think, would argue that this major defeat (which cost the Ostheer approximately 1,500 armoured vehicles) seriously damaged German faith in the value of armour. Although British and American tank production peaked in 1943 and declined thereafter, German (and Soviet) production continued to rise in 1944.12 Indeed there is no evidence to suggest that the Wehrmacht was prone to interpreting reverses such as Kursk as indictments of the general concept of the tank.

Figure 1.1. Comparative Performance Data of Selected Tanks

Date gives the year in which the tank first reached front-line units. Gun shows the calibre of the tank’s main armament. This determines the weight of shot/shell fired which in turn is a determinant of armour-piercing performance. Muzzle Velocity indicates the maximum velocity achieved by armour-piercing shell/shot (in feet per second). This is a function of the gun’s barrel length (as opposed to calibre), and is a primary determinant of armour-piercing performance. Frontal Protection indicates the ballistic protection conferred by the tank’s hull front (glacis). Where appropriate, this figure has been corrected for the significantly greater levels of protection produced by sloping armour plate. Road Speed, Road Range and Weight are self-explanatory. Sources: Tank Data (Old Greenwich, Conn.: WE Inc., no date); Charles M. Baily, Faint Praise: US Tanks and Tank Destroyers During World War II (Hamdon, Conn.: Archon Press, 1983); R.M. Ogorkiewicz, Design and Development of Fighting Vehicles (London: MacDonald, 1968), p. 83.

The Soviets habitually suffered large tank losses during their great offensives of 1943–45 but nevertheless continued to embrace armour as a central component of their ground forces during the postwar period.13 Even after the startling Israeli tank losses inflicted by Egyptian guided missiles during the initial stages of the October War (1973), the Soviet Army continued to augment its tank strength,14 which led at least one Western source to claim that there was no Soviet equivalent of the strident ‘tank-missile’ debate which had emerged in Britain and the US in the wake of the October War.

The debate in Western military circles that followed the Yom Kippur War over the viability of armour in a battlefield environment dominated by precision-guided munitions has had no visible parallel in the USSR….15

This, however, was not entirely the case. Soon after the war, Soviet Minister of Defence A.A. Grechko produced a sober and balanced assessment of its implications for the future of armour. Tanks, he suggested, had been rendered more vulnerable, and their employment on the battlefield had consequently become more difficult. Technological developments might subsequently improve the level of protection enjoyed by armour, but it would also prove necessary to devise more active means of degrading the effectiveness of anti-tank defences.

[T]he traditional method of improving the survivability ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 Introduction: Explaining the Tank Debate

- 2 The Development of Anglo-American Military Thought

- 3 Technology and the Tank Debate

- 4 Incremental Development and Obsolescence

- 5 The 1980s: Developments in Doctrine and Equipment

- 6 Doctrine and Design

- 7 The Future of Armour

- 8 Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Index