![]()

Part I

Comfort women, the Kōno statement, and the quest for truth

![]()

1 The Kōno statement

Its historical significance and limitations

Yoshimi Yoshiaki

Introduction

Prime Minister Abe Shinzō is widely known at home and abroad for his virulent criticisms of the 1993 Kōno statement, in which Chief Cabinet Secretary Kōno Yōhei admitted some degree of state and military responsibility for the so-called military comfort women system, officially acknowledging the forcible mobilization of victims during the Asia-Pacific War (1931–45) (see Appendix 1). On March 5, 2007, during his first term in office (2006–07), Abe told the Diet’s upper house that, “[I]t was not as though military police broke into people’s homes and took [women] away like kidnappers.… [T]estimony to the effect that there had been a hunt for comfort women is a complete fabrication.” On March 16, his Cabinet endorsed a statement asserting that among the documents identified by the government between 1991 and 1993, “we could find no specific reference to forcible recruitment by military or civil authorities.”1

Again, during the September 2012 intraparty election for president of the Liberal Democratic Party preceding Abe’s election to a second term in late December, he announced his intention to revisit the Kōno declaration. “Many people don’t realize that during my [first administration], the Cabinet issued a finding entitled ‘There was no coercion’,” he told a meeting of LDP Diet members. He added, “We must reaffirm the fact that the Cabinet decision has revised the Kōno statement.”2

Abe’s contentions are based on a rigid definition of forcible recruitment (kyōsei renkō) that has two correlates: (1) that such actions were carried out directly by military or civilian administrative personnel, and (2) that violence or intimidation was employed. The prime minister apparently thinks that unless both types of behavior were present simultaneously, recruitment could not have been, strictly speaking, coercive. He appears determined to construe “forcible” as narrowly as possible in order to minimize the scope of the word’s application and exonerate Japanese military authorities of wrongdoing.

As I show below, however, the Kōno statement is very clear in describing as forcible or coercive all actions taken against the will of the victimized women. Is Abe really correct in saying that the historical record does not support such a broad definition? In this chapter, I attempt to answer these and related questions by reexamining Kōno’s 1993 expression of guilt and remorse. I reassess the positive significance of his statement and conclude with a brief discussion of its shortcomings and how these might be rectified.

The paramount question of coercion

The key question to ask about the comfort women system is whether force was used to ensure compliance inside the comfort stations. In assigning responsibility for this system, it does not really matter whether the women caught up in it were transported to Japanese military installations aboard luxury liners, driven to their final destinations in limousines, or even gave their consent and came willingly. If they were forced to engage in sex with military personnel or the civilians in their employ in facilities under military control, then the Imperial armed forces are legally accountable for that system.

Kōno addressed this point in his 1993 declaration, noting cogently that the women “lived in misery at comfort stations under a coercive atmosphere.” This is a straightforward assessment of the issue. It is supported by the oral histories and court statements of numerous victims and is therefore difficult to deny. Survivors’ accounts, in turn, have been corroborated by the personal stories of former soldiers, sailors, and their civilian counterparts who availed themselves of the comfort stations, many registering their utter disgust at the appalling conditions they found there. Taking this a step further, if the comfort women system was a case of de facto institutionalized sexual slavery—which I am convinced it was—then the women providing sex there were obviously not doing so of their own will.

Table 1.1 compares Japan’s pre-World War II regime of state-regulated prostitution with the Imperial military’s comfort women setup. Both systems are forms of highly organized sexual servitude, with a few minor differences.

State-licensed prostitution and the comfort women system both denied inmates freedom of movement and choice in determining their place of residence. Interned women were obliged to live in segregated quarters that were tightly regulated and kept under strict surveillance.

Table 1.1 A comparison of Japan’s military comfort women system with prewar licensed prostitution

| Freedom of domicile | Freedom of movement | Freedom to quit without notice | Freedom to refuse work |

| Licensed prostitution | None | None, although in 1933, the Home Ministry directed that it be granted. | Legally recognized, but exercising this right was extremely difficult. | Entering this trade was considered a question of choice, but refusing a client was very difficult. |

| Military comfort women system | None | None | None | Refusing a client was virtually impossible. |

Legally registered prostitutes were known colloquially as “caged birds” because they were forbidden to venture outside the red-light districts without permission from their overseers. In 1933, the Ministry of Home Affairs issued a directive ostensibly lifting this restriction (see below). The measure was taken in response to international criticism that state prostitution in Japan constituted a form of human trafficking—a charge based partly on the permit system that limited licensees’ mobility. The ministry was intent mainly on rebuffing such accusations, and the order was never seriously enforced.

Women bound to comfort facilities had no freedom of movement at all. Military regulations governing comfort station operations often explicitly denied this fundamental right. For instance, standing orders drawn up in 1938 by the 2nd Independent Heavy Siege Artillery Battalion stationed in Changzhou, Jiangsu Province, China, state that “[i]t is forbidden for staff to go outside specially designated zones” (“staff” being a euphemism for comfort women).3 Placing all areas off limits except those specifically authorized by army officials effectively denied these women the liberty to move about unhindered.

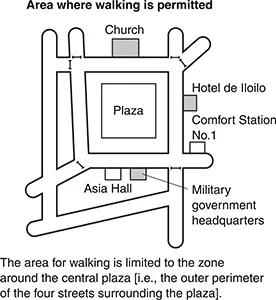

The Japanese Military Administration of the Philippines’ Iloilo office on Panay Island adopted rules in 1942 compelling army comfort station operators to “strictly control the outings of comfort women,” who were forbidden to leave the premises without express permission from the Iloilo office chief. The single exception was between eight and ten in the morning, when the women were allowed to take short walks, but even then, they were confined to a nearby park occupying the town square.4 Because a special permit was required to exit the comfort facility, freedom of movement was effectively suppressed.

The Home Ministry’s 1900 “freedom-to-retire” directive purportedly recognized the right of registered prostitutes in licensed quarters to leave whenever they wished, but the ministry had no intention of implementing it. In fact, the measure was virtually unenforceable. First of all, women working there were not told of the order’s existence. Even if they learned about it somehow, bordello keepers intervened to prevent them from submitting letters of resignation to the police, as required by law. Women lucky enough to successfully petition police authorities were almost certain to be sued by housemasters demanding repayment of the cash bonds they had advanced the victims’ guardians in order to secure their sexual labor.

In principle, Japanese law viewed employment contracts obliging women to pay off their debts through prostitution as a violation of public order and morality and therefore technically invalid. In almost every case that went to litigation, however, courts sided with brothel owners, issuing decisions that required the plaintiffs to clear all financial obligations before departing.5 The vast majority, who could not pay up, were returned to a life of bondage.

A Japanese court would not rule decisively in favor of a prostitute breaking her bond and changing jobs until 1955, ten years after the end of World War II. That year, the Supreme Court declared that any clause requiring a woman to repay a monetary advance by selling her body automatically voided the contract itself. The Anti-Prostitution Law of 1956 (effective from 1958) proscribed all forms of prostitution, although it left large loopholes. Until the Supreme Court verdict, the putative freedom to quit without notice was, with very few exceptions, meaningless, and licensed prostitution under conditions of debt slavery amounted to de facto sexual slavery. In the case of the comfort women, however, there was not even the pretense of a right to depart at will. Absent a special dispensation from their military overlords, the women were chattels, pure and simple.

Table 1.2 Military regulations for comfort stations (No. 1 Comfort Station and Asia Hall) in Iloilo City, Visayas, Philippines (November 22, 1942)

1 The following regulations apply to all matters concerning the management and operation of comfort stations in the area controlled by the Iloilo Office, Visayas Branch, Military Government of the Philippines. 2 The supervision of comfort stations shall be under the jurisdiction of the [local] military government. 3 The medical officer attached to the garrison shall be in charge of supervising hygiene [in the comfort stations]. Venereal disease examinations of women serving clients [there] shall take place on Tuesday of each week at 15:00. 4 Use of the comfort stations shall be restricted to uniformed military personnel and civilian employees of the military. 5 Comfort station managers shall scrupulously observe the following provisions. 1) Bedding in the buildings shall be kept clean and disinfected by exposure to sunlight. 2) Facilities shall be fully equipped for cleansing and disinfecting [to prevent the spread of venereal disease]. 3) Clients who do not use condoms shall be prohibited from availing themselves [of these facilities]. 4) Unwell women are prohibited from serving clients. 5) Comfort women shall be strictly supervised to ensure they do not leave the premises. 6) Women shall bathe daily. 7) All entertainment not covered by these regulations is prohibited. 8) Comfort station managers shall submit a report of daily business activities to military government authorities. 6) All personnel intending to use the comfort stations must strictly abide by the following rules. 1) Absolute vigilance must be exercised to safeguard intelligence [useful to the enemy]. 2) Comfort women and housemasters shall not be subjected to violence or intimidation. 3) All fees must be paid in advance in military script. 4) Clients must use condoms, scrupulously maintain personal hygiene, and do their utmost to avoid contracting a venereal disease. 5) It is strictly forbidden to take comfort women off the premises without permission from the Iloilo Office, Visayas Section, Military Government of the Philippines. 7 Comfort women shall be permitted to take walks every day between the hours of 8 a.m. and 10 a.m. If they wish to do so at other times, they must have permission from the Iloilo Office, Visayas Branch, Military Government of the Philippines. Furthermore, they are required to remain within the area shown in Figure 1.1 below. 8 Use of the comfort stations is restricted to personnel holding an authorized military pass (or its equivalent). 9 The comfort stations’ hours of operation and fees are to be posted separately. |

Source: Yoshimi, Y., ed. (1992). Jūgun ianfu shiryōshū (Historical documents on military comfort women). Tōkyō: Ōtsuki Shoten, pp. 324–26.

Could a woman refuse a client? Prostituted women registered by the state were considered to have elected their occupation. But, once a woman’s guarantor had accepted a cash loan from the proprietor and signed a contract, it would not have been easy to turn down a paying customer due to the extreme pressure she was under to fulfill the terms of her indenture. For comfort women, on the other hand, sa...