![]()

II

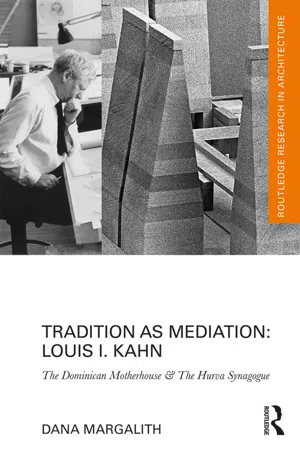

Kahn’s Designs

Kahn’s Designs, the crux of the book, explore the manner that Kahn’s unique approach towards tradition, history and memory was implemented in his design for the the Dominican Motherhouse St. Catherine de Ricci and his design for the Hurva Synagogue. It investigates how Kahn renegotiated with the past, using tradition, history and memory as poetic fields of knowledge to generate new modern institutions in times of flux. Both parts expose the manner that Kahn dealt with issues related to the conception of time-space, ritual and religion immanent in history, tradition and memories, to which his design projects refer. The chapter presents how these were re-interpreted by Kahn in his designs tied to a shared past, concerned with the present, and open to interpretation, contemplation, desires and will for an unknown future.

Part 1 investigates Kahn’s renegotiation with the past in his design for the Dominican Motherhouse St. Catherine de Ricci, Media, Pennsylvania, USA – a Motherhouse, built for Mendicant Dominican Sisters. The Dominican tradition is rooted in monastic cloistered convents, but the work on the Motherhouse took place at a time of renewal of the Catholic Church after the Second Vatican Council, the revival of a more secular religion after WW II, and in a feminist social democratic American atmosphere. The chapter explains Kahn’s new architectural challenge in this specific state of transition, studies Kahn’s design process and analyses and evaluates Kahn’s design proposals. It demonstrates how Benedictine and Cistercian cloistered monasteries served Kahn as Proto Forms – whose images, programs and narratives expressed weak cultural and religious truths that were questioned and challenged by Kahn. It analyses how traditional concepts of Solitude and Communality; Routine and Order; Work and Study; Contemplation and Action; and Hierarchy, were redefined by Kahn in his design proposals that brought forth the Sisters’ Dominican-Feminist-Democratic future desires while preserving ties with the Sisters’ traditional origins. The chapter ends with an attempt to explain the reason that Kahn’s designs were not built, and evaluates this missed opportunity.

Part 2 investigates Kahn’s renegotiation with the past in his design for the Hurva Synagogue – a Synagogue whose origin is rooted in ancient Hebraic and diasporadic traditions, built in the context of a modern Zionist secular Jewish State. It explains Kahn’s new architectural challenge in this specific context, studies Kahn’s design process and analyses and evaluates his design proposals. It demonstrates how archaic biblical structures, the Tabernacle, the Temples in Jerusalem, the Historical Hurva Synagogue, and other Rabbinic Synagogues served Kahn as Proto Forms – whose images, programs and narratives expressed weak cultural and religious truths that were questioned and challenged by Kahn. It analyses Kahn’s design in terms of traditional concepts of Placement, Orientation and the Concept of God’s ShKciNah, The Preference of the Oral and the Suppression of the Visual and the Tactile, Borders and the concept of Purity, The Concept of Aliah (עליה) – Ascension, The Jewish Idea of Time and the concept of the Messianic Future. Kahn redefined these notions through his design propositions, bringing forth the potential to define future Jewish-Israeli-Zionist rituals while preserving ties with Hebraic and diasporadic traditional origins. The chapter ends with a comparison between Kahn’s meaningful unbuilt proposal and the Synagogue which was actually constructed (2010), and evaluates this missed opportunity.

![]()

Part 1 The Dominican Motherhouse of St. Catherine de Ricci, Media, Pennsylvania, 1965–1969

On the brow of a hill, in a Philadelphia suburb, one can find the compound of the Motherhouse for the Dominican Sisters of St. Catherine de Ricci. Driving uphill on Providence Road towards the Motherhouse, one encounters a green landscape, scattered with partially-built walls and fragmented, sunken tunnels. In their position and proportions, they echo the Motherhouse’s structure. In fall and winter the Motherhouse can be seen clearly through the tree’s branches. In the spring and summer the building is hidden among blooming trees; the traces in the landscape are more apparent than the building. A visitor to the Motherhouse will arrive, depending on the season, at either a prominent monument or a secluded compound, remote and surrounded by vegetation. The site changes with the seasons, both physically and symbolically. The building is experienced at once as sacred and out of reach, and as tangible and accessible. 50 meters from the Motherhouse the car journey reaches its end. The traces of vegetation and the fragmented structures make driving further impossible. The area looks like an archaeological site. Even a layman would recognize the relationship between the structure of the Motherhouse and the landscape, which reads like an extension or trace of the building. Here a cubical structure on the ground has the same dimensions as the Motherhouse gate 50 meters away; there a paved area creates a place between church and half-built wall, giving the impression of a deserted, unroofed narthex. Water travels from the Motherhouse’s structure outwards, down the brow of the hill, towards a pool located outside the complex and against its surrounding wall. The Motherhouse physically, acoustically and poetically “pours” out and empties. The feeling is ambiguous – the fragments and traces on the ground, together with the freshness and emptiness of the area surrounding the Motherhouse, give the feeling of a place which has just been born; or the opposite, a place that is disintegrating.

After few minutes of walking one comes to the entrance. A massive built structure, three stories high, welcomes the visitor. In its fourth floor is a large empty opening; a bell tower without a bell. Conventual time is absent. The entrance structure has no gate; it is open, and nuns and laymen travel through its many stories. It is a meeting place. Where is the boundary between the secular and spiritual worlds? But the entrance is a dead end. One cannot go through. A narrow opening allows a view of the interior of the Motherhouse – a small empty place. It is surrounded by buildings which turn their back towards it, and cast their shadows on it. The place is deserted and quiet. Is this the cloister? And if so, what has happened to it? How can one reach it? Moreover, if one does, what will one do there? Burn under the sun? Where are the well, the cultivated garden? It is as though one of De Chirico’s enigmatic sites has come to life.

The sisters can reach their rooms, located in three fingers surrounding the communal buildings, either from a separate staircase next to the gate, or through several other public structures – all intersecting the corridor that connects their cells. Thus, every sister can choose her own schedule. Is there a communal routine in the Motherhouse? Or is everything pursued according to private intentions? The architecture encourages democracy, and makes routines difficult to follow. From the corridor connecting the cells, small openings allow views to the deserted residual courts, irregular spaces left over between the public wings of the building.

The sisters’ rooms feel both secluded from the surrounding area, and part of it. Thick-walled, they feel stable, and sheltered by the Motherhouse; however each room enjoys a wide window with views to the horizon, allowing every sister to “create” her own world – a place, oriented outwards, with the potential to dream and reflect. Movable screens allow the sister to close her window, and change its atmosphere to an intimate secluded room penetrated by only a few rays of light. The “luxury apartment” can change to a “spiritual cell.” Above the cells a communal open roof allows the sisters to meet. The openings of its bounding wall are unglazed, allowing vegetation to grow through them. Were these once used as dorters? Or is this just a leisure terrace? The greenery overgrows the unfinished structure; again, the atmosphere changes according to season. Sometimes, ...