![]()

Part I

Entrepreneurial discovery processes and their institutional challenges

![]()

1 Self-discovery enabling entrepreneurial discovery processes

Seija Virkkala and Åge Mariussen

1.1 Introduction

The future is unknowable and the global environment turbulent. Nobody is capable of presenting an overall view of how technological and market opportunities will influence regional development. The solution to this dilemma proposed by the EC smart specialisation policy involves governments, companies, universities, and other actors or quadruple helix stakeholders uniting to identify future growth opportunities (Radosevic, 2017b; Foray, 2017). The method governing that search is the entrepreneurial discovery process (EDP), which is a collective idea generation mechanism addressing the future of the region in terms of the knowledge economy. The EDP and smart specialisation have the same meaning as practices and approaches to diversify the regional economy. The aim is to expand the regional economy in a direction identified by the relevant quadruple helix stakeholders (i.e. entrepreneurial actors). This is a pressing policy concern, particularly at times of significant restructuring in the world economy, given the relatively slow transition to a more prosperous knowledge economy in parts of Europe.

Regional development is often considered in economic terms as a question of growth, but in this book it is defined more broadly in line with the Europe 2020 targets for smart sustainable and inclusive growth as also addressing social and ecological policies such as diminishing social inequality, promoting environmental sustainability and championing inclusive government. The broader definition includes implementing smart specialisation strategies (S3). Development is a change of direction, but smart specialisation and EDP particularly emphasise the renewal of the regional economy. S3 is an economic transformation agenda built on each region’s strengths. The new business areas or fields of opportunity (domains) which are discovered through the broad partnership are expected to initiate structural changes in different forms: diversification, transition, modernisation, or the radical foundation of industries and/or services (Foray, 2015: 1) – in other words path renewal, path extension or new path creation, in the terminology of economic geography (see Isaksen et al., 2019 – Chapter 2 in this volume).

According to the Smart Specialisation Platform (EC-JRC, 2017):

The notion of the EDP can be viewed from different perspectives. Rodríguez-Pose and Wilkie (2017) have related the concept of the EDP to an institutional approach by decomposing EDP into three elements (entrepreneurial actors, experimentation and discovery, and the interaction between relevant actors) and exploring the way that institutions interact with these components. They also point to the need to adapt EDP to contextual factors (see also Gianelle et al., 2016). Others, like Morgan (2017b) and Aranguren et al. (2017), explore the human element in smart specialisation governance. Aranguren et al. (2017) examine the concept of smart specialisation with the aid of leadership theories and emphasise the process view on governance.

The notion of self-discovery is related to the EDP and emphasises the concept of agency. Hausmann and Rodrik (2003) state that self-discovery means to discover what economic activities can profitably be pursued in a given country, given the existing strengths and specialisations of the national economy. The latent competitive advantage of nations or regions can be discovered in broad partnerships. In terms of regional development policies, self-discovery refers to a region’s strengths and unique assets that can form the basis for future business fields.

This book highlights the relations between exploitation and exploration in the context of EDP. Exploitation refers to using existing knowledge to refine existing processes; exploration refers to the discovery and creation of new knowledge. Exploitation crowds out exploration and vice versa (March, 1991). Strong clusters tend to lead to exploitation rather than exploration. Innovation systems oriented towards exploitation may restrict entrepreneurs who try to create new paths. This is where the EDP can contribute by pushing innovation policy and research supporting innovation policy in the direction of more exploration.

This book aims to answer the research question: How is the transition from exploitation of knowledge to exploration and discoveries possible, and what are the implications for the actors involved, for the transformation of the regional economy, and for knowledge production and creation?

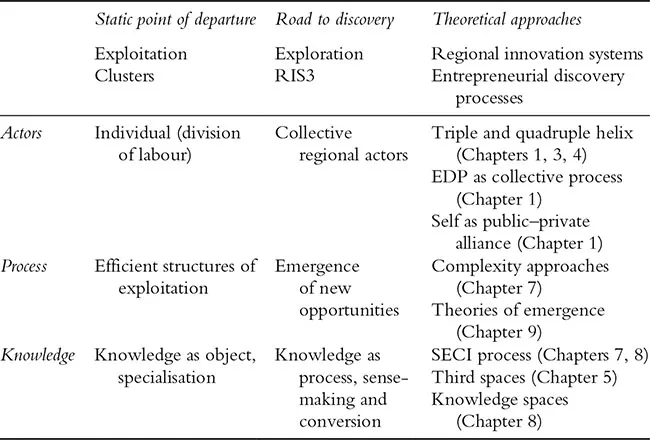

This chapter examines what the ‘self’ in self-discovery is; more specifically, it investigates what is required for actors to make the transition from exploitation to discoveries in regional development (Table 1.1). Chapter 9 (Virkkala and Mariussen, 2019) analyses the implication of this transition to exploration for the transformation process of regional economy, and Chapter 5 (Lam, 2019) and Chapter 8 (Virkkala, 2019) focus on the knowledge creation and knowledge space needed for the discovery. The actors, the process, and knowledge are indistinguishable elements despite being addressed separately for the purposes of analysis. In real-life EDPs, these analytical elements interact in the processes of exploration, failures, success and exploitation.

This chapter focuses on self-discovery enabling the EDP. The EDP begins with fragmented knowledge that must be combined, and which, together with additional knowledge resources, is necessary for exploration. The EDP is a move from a state of knowledge and actor fragmentation to a process of self-discovery. Along that road, the fragments of knowledge objects come together into a new, living entity – knowledge as process – that offers a new cognitive understanding of the opportunities available to a region. The start of this journey of self-discovery requires a creation of a collective actor capable of pulling things together and in that way makes sense of the opportunities available to the regional economy in a new way. This point of departure will be discussed in the second section of this chapter, which gives an overview of the process from fragmentation (of knowledge) in the exploitation phase to emergence of a new domain of opportunities for new value creation. In the third section of this chapter, EDP and S3 will be compared with approaches often used in regional development strategies: the cluster approach and the innovation system approach. EDP is an attempt to overcome the shortcomings of policies based on theories of regional innovation system, or RIS. The RIS tradition has been criticised for being too static and not providing relevant policy advice. The RIS literature ‘is nearly silent on the conditions that enable growth to accrue in regions where innovation occurs’ (Doloreux and Porto Gomez, 2017).

The fourth section of the chapter summarises some critical reflections on the EDP. This chapter presents preconditions that can trigger a change from exploitation to exploration in which the EDP provides a potential solution. The first precondition is to change the static structure to a more complex and dynamic process by moving focus and policy measures from the micro level to the macro level. The second precondition is to recognise the tacit character of knowledge as well as the interaction processes leading to the knowledge spiral, in other words, a continuous EDP. The third precondition is to make the EDP a transnational discovery process. These preconditions can be seen as challenges meriting further examination and will be discussed thoroughly in the later chapters of the book.

Table 1.1 Framing elements of the regional self-discovery process

Source: Own elaboration

1.2 The EDP: collective actors searching for new domains

Background of the notion of the EDP

In order to understand the role of collective actors in the EDP, this chapter first introduces the background of the EDP in a stylised way. The concepts of entrepreneurial opportunities and discoveries are used in business and entrepreneurship studies (Shane, 2003) and they originate from Austrian economists such as Hayek (1945; 1978) and Kirzner (1973; 1997).

Entrepreneurs are continually searching for, identifying and evaluating new business opportunities. This process is called entrepreneurial discovery in the business theory literature (Shane, 2003: 3–6). Entrepreneurship requires the existence of opportunities, or situations in which people think that they can recombine resources to generate profits. Entrepreneurship can be characterised as the reaction of certain individuals (entrepreneurs) to the existence of opportunities for profit. However, the exploitation of opportunity is uncertain because it depends on demand, competition and the opportunity to create a value chain. The individual entrepreneur exploits an opportunity and organises and recombines resources in a way that they have not been previously. The opportunities an entrepreneur exploits are created, for instance, by social/demographic change, technological change, and political/regulatory change, as well as by grand challenges like climate change (Shane, 2003).

The Austrian economists saw market equilibrium as a process through which market participants acquire accurate knowledge of potential demand and supply. The Austrian approach nominates entrepreneurial discovery as the driving force behind the process. Kirzner (1973) pointed out that opportunities are discovered through entrepreneurial alertness, and that better knowledge leads to competition and a new equilibrium. Entrepreneurial processes are seen as carried out by the actions of business entrepreneurs profiting from temporary disequilibrium.

The notion of self-discovery was later used by Rodrik (2004) and Hausmann and Rodrik (2003) on a macro level when they wrote about national economic development. Self-discovery means to discover what economic activities can profitably be pursued in a given country, given the existing strengths and specialisations of the national economy. Self-discovery can benefit the whole economy, not just the firm that originally invested in the discovery, and accordingly, governments should implement economic policies that promote self-discovery.

The concept of smart specialisation was developed in the Knowledge for Growth group as a response to the economic crisis and growth problems in the EU (Foray, 2015). It quickly diffused into mainstream EU regional policy and has been used as an ex-ante condition for Structural Fund (SF) programmes since 2014 (Gianelle et al., 2016; Grillo, 2017). The strengths of the region (the ‘self’) should be found jointly in public–private alliances. Entrepreneurial discovery is the source of information on the new exploration and transformation activities which should be supported in Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialisation (RIS3). The planners of RIS3 suggested a learning process to discover the business fields in which a region might hope to be competitive.

According to Radosevic (2017b), S3 applied in the EU is one approach to so-called new industrial policies which support diversification and technological upgrading. According to these policy approaches, the constraints of growth and new possible business fields are not known ex ante, and the design of the discovery process is important. Instead of an a priori defined policy target, search networks should be established to examine technological change and its effects (Radosevic, 2017b: 7). Radosevic (2017b) includes among the new industrial policy approaches Rodrik’s notion of self-discovery, diagnostic monitoring (Kuznetsov and Sabel, 2017) based on experimentalist governance, and the product space approach set out by Hausmann and Hidalgo (Hausmann et al., 2011; see Nguyen and Mariussen, 2019 – Chapter 10 in this volume). In addition, approaches such as new structural economics, neo-Schumpeterian and Schumpeterian perspectives emphasising targeting industries that constitute the country’s latent comparative advantages can be included among the new industrial policies.

The shift of emphasis from individual to collective entrepreneurship has implications for the process of learning, and these are examined below.

The Austrian approach to microeconomics: the individual entrepreneur and discovery – Hayek and Kirzner

The notion of discovery is central to the Austrian approach. Entrepreneurs drive the market process, and the entrepreneurial role offers a theoretical explanation for its ever-changing nature. Hayek (1945; 1978) emphasised the nature of competition as a discovery procedure. He interpreted the market process as a process of mutual discovery, during which the market participants become better informed of the plans made by other participants. Some plans must prove to have been mistaken; they are seen as errors which tend to be overcome as market experience reveals that they are not viable when some other actions prove themselves profitable. Decision-makers might discover that a plan is not viable when a prior error in their view of the world is revealed, and they can then correct the view. Earlier plans might have overlooked existing profit opportunities, but such opportunities might be reflected in later plans. This example also offers a new insight into the nature of discovery: when people become aware of what they have overlooked previously, their view of the world will change. Discovering previously unknown profit opportunities is different from a successful search based on the deliberate production of information that was known to be missing. Discovery means that surprise comes with the realisation that something that was in fact available had been overlooked. Discoveries occur because human agents are alert (Kirzner, 1973), and the alertness expresses itself in the boldness and imagination. Alertness also means an attitude of responsiveness to available opportunities. The entrepreneurs search for unnoticed features of the environment that could inspire new activity and lead to discoveries.

Kirzner held that entrepreneurial discovery occurs because the price system does not always allocate resources effectively. People’s views on the efficient use of resources are based on incomplete information. Their inaccurate decision-making framework can prompt people to make erroneous decisions, which in turn create shortages and surpluses. By responding to these shortages and surpluses, people can obtain resources, recombine them and sell the output in the hope of making a profit. The earlier errors create profit opportunities and tend to stimulate successive entrepreneurial...