Labour unrest, political intrigue, massive demonstrations and ultimately bloody revolutions were all nurtured by the poverty and despair which were as much a part of industrialisation as the factories themselves.1

If you ask someone in 2017 to say what they associate most with modern day St. Petersburg, they will probably reply the beautiful palaces, bridges and art galleries. At the start of the twentieth century although some of these symbols of luxury existed, the city also had its underside – factory chimneys, badly lit streets, wooden houses and rubbish piled up and it was generally viewed as an unhealthy place to live. This chapter, which offers radically different interpretations to existing historiography, sets the scene for the central argument that the Tsarist state failed to protect the ‘body Russian’, in particular poor peasants and the rising industrial working classes. This was because the government management of budgets and public health was seriously flawed. A fundamental change of system was deemed necessary to launch a reorientation of public health, and the Bolsheviks and radicals within the medical profession, were at the forefront of this movement.

This chapter analyses the main trends in public health and sanitation from the mid-1850s until the October Revolution of 1917. Four themes predominate: first, an assessment is made of the patterns of illness and disease in the Russian capital; second, we analyse the municipal authority’s response to this situation; and third, the view of the emerging the medical establishment to these issues is outlined. The factors explaining the high levels of disease, illness, poor hygiene, cleanliness and overcrowded housing are discussed, including lack of money, the failure on the part of the municipal authorities to take the necessary initiative, and the Russian elite’s poor commitment to the population’s needs, and the ineffective management of local health and welfare services. It is also shown that this was also a time of medical professionalization, and the battle with the state over this goal, together with differences between radicals and conservatives within the medical profession, compounded an already difficult public health situation. The final and fourth theme is the role of the Bolsheviks, their assessments of Tsarist policies, connections with radicals within the medical profession and the shared notion that the Tsarist regime and its institutions had failed to protect the health and welfare of poor peasants and rising industrial working class. This point is emphasised through a case study of social insurance. This approach offers us insights about what the main flaws of the tsarist health system were and what the Bolsheviks thought was required to eradicate them.

Life and death in St Petersburg, 1854–1917

The first part of this section analyses changes in demographic, health and sanitation patterns with an emphasis on the impact of industrialisation and urbanisation on public health conditions in the capital and how the municipal authorities and medical profession dealt with the challenges posed by water supply contamination, poor sewage, inadequate housing and the outbreaks of infectious and other diseases that followed. We argue that medical issues increasingly became a political issue and as a result medical students and doctors moved beyond the desire for professionalization to pursue broader political goals.

Population growth was slow between the 1850s and mid-1880s but increased after 1895, due to the arrival of immigrants from the countryside and other cities of the Russian Empire a consequence of the railways, the growth of industry and the development of trade and commerce. James Bater points out that prior to 1890, the annual net increment in St Petersburg averaged about 15,000 people, but thereafter averaged roughly 50,000 in the dozen years up to the First World War.2 The data furnished in Table 1.1 shows, by 1917 Petrograd had a population of 2.3 million, making it the fifth largest city in Europe.

By December 1912, the city of St Petersburg employed nearly 189,000 industrial workers in its factories and mills,3 and although this growth is important, for reasons explored below, it is essential to realise that there were more servants that those working in manufacturing or construction according to the 1910 city census, with other people working in catering, local government, trade, insurance and transport.4 Thus what in Soviet parlance was termed the ‘collective’ was relatively small at this point.

Table 1.1 Population of St Petersburg and Petrograd, 1895–1917

| Year | Size of population |

| 1895 | 1,202,100 |

| 1900 | 1,418,000 |

| 1905 | 1,635,100 |

| 1910 | 1,881,300 |

| 1914 | 2,217,500 |

| 1915 | 2,314,500 |

| 1916 | 2,415,700 |

| 1917 | 2,300,000 |

Sources: Obshchii svod’ po imperii rezul’tatov razrabotki dannykh perepisi naseleniia, proizvedennoi 28 ianvaria 1897 goda (St. Petersburg 1905), 2; XV let diktatory proletariata: Ekonomiko-statisticheskii sbornik po gor. Leningradu i Leningradskoi oblasti (Leningrad 1932), 135 and S. A. Novosel’skii, Demografiia i statistika (Izbrannye proizvedeniia) (Moscow “statistika" 1978), 102.

The population of St Petersburg’s growth was the product of the arrival of migrants who accounted for more than 80% of the increase in St Petersburg’s population between 1870–1914.5 In 1869, most of these peasant workers came from Iarovslavl and Tver (over 38% between them) and by 1910, nearly 33% of Petersburg migrants still came from these two regions, with the rest coming from Novgorod, Kostroma, Pskov, Riazan, Moscow, Smolensk and Vitebsk.6 McKean argues that these immigrants came from areas that

were characterised by a lower soil fertility than average, (had) a higher proportion of the population engaged in secondary industry, and consequently a lower ratio of involvement in traditional agriculture (and) a significant rate of out-migration and (by) the greater literacy of its inhabitants.7

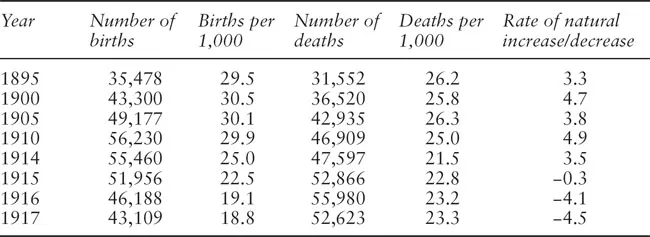

The problem was that this urban demographic revolution put extreme pressure on the quality of the environment and space which in turn affected the birth and death rates. Data collected by the Petrograd statistical bureau shows that the birth rate stood at 32 per 1,000 inhabitants in 1850.8 Table 1.2 indicates that the birth rate remained steady at around 30 until 1910 but then fell until it reached 18.8 by 1917. The death rate was also declining from 30 per 1,000 in 1850 to 23.3 by 1917. In 1913, on the eve of war, St Petersburg’s birth rate of 28.7 was slightly higher than that of London, Amsterdam, Milan, Stockholm and Paris whilst St Petersburg’s death rate of 26 per 1,000 in 1900 was higher than that of Berlin, London, Paris and Vienna.9

One reason for this trend in birth rate in St Petersburg was the increase in the total fertility rate among women aged 15–44 years, which rose from 3.82 in 1900 to 5.23 by 1910. Later marriages and a declining infant mortality rate from 27.0 in 1897 to 23.6 by 1913, undoubtedly helped too, although the First World War, a high level of abortions, unsanitary housing conditions and female unemployment, created a lack of security and caused severe financial hardship affecting people’s decisions on whether or not to start a family.10

Table 1.2 Birth and death rates in St Petersburg and Petrograd, 1895–1917

Sources: Materialy po statistika Leningradu i Leningradskoi gubernii, Vyp. 6 (Leningrad 1925), 202 and S A Novosel’skii, Demografiia i statistika (Izbrannye proizvedeniia) (Moscow “statistika" 1978), 102

Because of the high level of spatial mobility within St Petersburg, no district of the city of St Petersburg was socially homogeneous and all parts of the city contained a mix of different social classes. Between 1869–1910, the nobility tended to reside in the city centre; merchants and honoured citizens in Vasil’evskii island, near places of commercial activity and the working class in Petersburg side, Moscow and Narva districts of the city.1...