![]()

1 Introduction

The last three decades have witnessed a concerted effort on both sides of the Atlantic to build and develop programs that are explicitly designed to support and promote democracy around the globe. The immediate post-Cold War period created a narrative that permitted engaged states to justify investments into such activities to their publics and to legitimize their benign interference into the internal affairs of target states on the international scene. The narrative deemed that in the absence of a structural obstacle (the communist Soviet bloc), countries would innately adopt democracy as their political model of choice, inseparably followed by the application of market economy principles. History would thereby reach its “end” – to use Fukuyama’s words1 – as democratic peace (i.e., the theory that democratic nations never fight each other2) and economic interdependence along with a post-Westphalian conception of state sovereignty would effectively render war and military conflict among states rare or extinct. Also – from a teleological perspective – by becoming democratic, society would reach the endpoint of cultural evolution and accept democracy as the final form of human government.

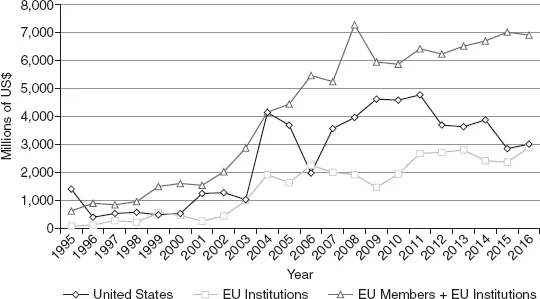

With these normative, material and teleological perspectives in mind and to speed up this new path of global progress, “Western” democratic countries started implementing policies explicitly tasked to foster democracy around the world. In the case of the United States, such policies were implemented already in the early 1980s, while the European Union (EU) created its first instruments to assist democracy in third countries at the turn of the 1980s and the 1990s. Since then, democracy assistance has evolved into an “industry” that is steadily growing (see Figure 1.1). As a consequence, the topic has basically become an academic research field of its own, receiving attention from scholars focusing on democratic transitions, democratic theory, national and international security and policy-making.

Most authors, however, have been examining impact of democracy promotion – that is, they have placed their attention on the recipient states and on evaluating (quantitatively and qualitatively) the effects of democracy promotion policies.3 This is understandable as governments strive to see what effects the programs they fund have on recipient societies and political systems and the only way to optimize efficiency is by being aware of deficiencies and real outcomes that have deviated from the “plan.” This book will place the recipients at the sideline and focus rather inwardly – at the donors themselves. Our aim is to place the approaches (by which we mean the set of strategies, focus and tactics) of the US and EU institutions in perspective, typify the differences in these approaches and make sense of these differences by probing into the democratic identity of the actors and hence identifying the models of democracy each of the two actors promotes.

Figure 1.1 “Government and civil society” funding as part of ODA.

Source: author, OECD-DAC.

A common goal (?)

At least on the rhetorical level, the common goal of the United States and the EU in the task of promoting democracy is evident: assisting the emergence and consolidation of democratic regimes in third countries. The desired consequences of this shared activity are also clear: democratic regimes are less prone to enter into an armed conflict with other democracies; democratic regimes are – by institutional design – most likely to accommodate the desires and interests of the widest array of the domestic population, while preserving their political and civic freedoms; and, given their transparency, democratic regimes have proven to be more predictable partners in the international system than authoritarian regimes and thereby contribute to systemic stability.

However, as the words of Georges A. Fauriol, then Senior Vice President of the International Republican Institute (IRI), conclude, “The United States and Europe share similar goals in supporting democracy […]. Our approaches, however, often differ significantly.”4 Former Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor in the George W. Bush administration, Lorne Craner, allegedly called the disparities in the US and EU approach to democracy promotion “variations in views with common goals.”5

In practice, a lack of convergence of strategies leads to situations when actors involved in the democracy assistance agenda:

… embrace different versions or elements of liberal democracy, and may compete and clash in their efforts. Furthermore, these actors and other NGOs, domestic and international, may clash over specific goals like markets versus social justice, over tactics, and other issues […].6

Such misunderstandings quite obviously complicate or even hinder the attainment of the common goal.

A deeper understanding of these “transatlantic variations” in democracy assistance is necessary both in a practical and theoretical sense. In terms of applied research, it will help actors across the Atlantic comprehend each other’s strategies and potentially give incentives to find ways to complement – if not synchronize – each other more comprehensively. In terms of theory, juxtaposing the different approaches to promoting democracy will provide a window into how both actors – the US and the EU – project their versions and conceptions of democracy and the ensuing role of the state in an individual’s life into their democracy assistance agendas. Such research will thereby highlight the different aspects of democracy the two actors believe are valid for recipient countries and it will also tacitly show which aspects both actors deem to be imperative for a functioning democratic system.

In this sense, the present publication’s chief goal is to demonstrate that the source of the different strategies and tactics applied by the US and EU institutions in promoting democracy is the divergence in the definitions of democracy formulated in their democracy promotion agendas. These conceptualizations of democracy can in turn be linked to the democratic identities of both actors.

In other words, as the policies of both actors emanate from different normative backgrounds (albeit still maintaining the same common goal of democratization), the substance of their respective democracy promotion agendas does not fully converge and thereby the two actors adopt different approaches in pursuing their respective democracy promotion agendas. Consequently, were we to hypothetically compare EU democracy assistance in country X and US democracy assistance in country Y (with both country X and Y having identical default characteristics), we would likely witness two different outcomes of their activities – i.e., we would see different organizations of the political and social life in the two target countries as both actors would “teach” the recipient a different form of democracy even when being sensitive to the specifics of the receiving state’s domestic context.

The proposed research agenda is much needed as pundits have observed that, while “academic research has amply described the differences between EU and US democracy assistance, the explanations for these differences have often been neglected.”7 Similarly, Wolff and Wurm argue that in current literature it is mostly “the mechanisms [the ‘logics,’ ‘targets,’ and ‘pathways’ of influence], through which different democracy-promotion policies impact on domestic political change that receive theoretical interest,” but these fail to provide “a theoretical account that might predict/explain/help understand variances and commonalities in US and European strategies.”8

Thus, we propose that unraveling the understandings and conceptualizations of democracy of both actors will help us understand why the US and EU institutions employ different tactics and strategies of promoting democracy. Since each actor envisages a different end-product of its democracy promotion efforts (i.e., a different form of democracy), the two may not fully agree on how democratization of a target state should be brought about. Therefore, we can even question whether both actors, in fact, have a common goal. Of course, the shared objective is to foster and assist nascent democratic regimes, but if we look closer at the form of democracy each actor aims to promote, we see that the end-goal is not as mutual as it would seem at first sight.

The essential contestability of democracy

It has become commonplace after the end of the Cold War to refer to a “Western liberal democracy” that is (and ought to be) at the heart of democratization processes around the globe. This notion was soon put under post-modernist criticism and challenged not only because democracy in third countries should be adapted to local socio-cultural circumstances, but also simply because there is barely a consolidated “version” or definition of a “Western liberal democracy” as such. Moreover, “democracy” itself is a contested concept.9 In this sense, Schmitter and Karl have warned that Americans should be careful not to identify the concept of democracy too closely with their own institutions as there exists no one form of democracy and that democracies are not more or less democratic but can be democratic in different ways.10 Similarly, the limitations of advocating a (single) liberal conception of democracy in the world are recognized by Peter Burnell:

[T]he notions of democracy that lie at the centre of much democracy assistance, while not all being identical, occupy a limited range. First, they are a political construct. Ideas of social democracy and economic democracy are excluded. Second, they are informed by individualism rather than by expressly communitarian notions of society. Third, although many of the formulations specify a range of freedoms and other qualities going well beyond mere electoralism and they should not be confused with “illiberal” democracy, even so there are few concessions made to the most radical models of participatory democracy.11

Burnell, however, acknowledges that there are nuanced differences between the “versions” of democracy advocated by democracy promoters. He adds that the “different democracy assistance providers are culture-bound to offer their own experience, specific preferences and prejudices in respect of democracy, and these can vary considerably even in respect of seemingly technical matters […].”12 This, of course, is not a surprising conclusion as constructivist approaches in international relations (IR) theory show the mechanisms of how culture and values shape and influence policy-making.

Yet, despite these calls for caution against viewing democracy as a single, universally-applicable political system, Hobson sees that the:

… feature that defines most of the literature and practice of democracy promotio...