![]()

1 A weekend in the Boland

Sites on the highway

In a book concerned with the politics of memories of South Africa’s violent past, it seems appropriate to begin on the shores of Cape Town’s Table Bay, at the foot of Table Mountain, at one of the first scenes in the long drama of European colonization in southern Africa. It was here, three and a half centuries ago, that a group of Dutch merchant-colonists established a small settlement that would by turns become a lonely fort, a thriving refreshment station for European ships passing around the Cape of Good Hope, an expanding Cape Colony, and, eventually, Cape Town, the “Mother City” of South Africa. This shore, now mostly harborfront, marks the site of one of the first skirmishes in the long and deeply troubled encounter between Europe and southern Africa, one distinguished by violence and subjugation, by collusion and cooperation, by brutal separation and by furtive and ambivalent border-crossings. The Dutch did not arrive in a land free of conflict—there were tensions in and between indigenous communities as there are everywhere—but the violence the European arrival initiated is at the historical heart of the memories being dealt with in post-apartheid South Africa.

In its current incarnation, the city center, from a distance, appears serene, with little of the hectic urban energy often associated with Johannesburg, its much larger cousin to the north. Its tall buildings and dense, leafy residential areas fill the “city bowl”—formed by the curving cliffs of Table Mountain and the summits of Devil’s Peak and Lion’s Head—to capacity. These mountains frame and contain the small city center. Nearly four million people live in the greater Cape Town area, but only a small fraction live in this central district. The remainder can be found tucked around the eastern corner of Devil’s Peak, some nestled in the middle-class suburbs that line the rear slopes of Table Mountain and the rest spread out on the vast open coastal plain of the Cape Flats. It is on these roughly 1,000 square miles of sandy flatland that the majority of Cape Town’s impoverished, working class, and lower-middle class residents live.

The main routes through this wide expanse of factories, high-rise apartment buildings, houses, shacks, and commercial districts are four highways that all originate at the edge of the city center. As products of apartheid urban planning, highways in South Africa faithfully mirror the old social and political policies of “separate development.” In Cape Town, for example, these four highways, the N1, the N2, the M3, and the M5, each connect the city center with Cape Town’s outlying white Afrikaans-speaking, black, Coloured, and white English-speaking areas, respectively. This careful cartography is, of course, not perfect, and exceptions, contradictions, and border-crossings inevitably surface along these highways. For the most part, though, the geographical logic of apartheid can still be easily grasped by driving along these roads.

During my fieldwork, the N2 highway stitched together many of the places where I conducted research. Ten minutes out on the N2 from the city center is the suburb of Observatory. “Obs” is one of the many English-speaking, predominantly middle-class suburbs that wrap around the foot of Table Mountain and it has enjoyed a reputation similar to the former Cape Town neighborhood of District Six for its tolerance and multicultural atmosphere. Obs is also a favorite sanctuary for the many visiting researchers, students, journalists, and artists from abroad. With its reputation for diversity and open-mindedness, and its easy access to the city center, to the University of Cape Town, and to the string of townships further along the N2, Obs has become an increasingly globalized meeting ground for those coming to experience and report on the “new” South Africa.

As you leave Observatory on the N2 and head out into the Cape Flats, on one side of the highway lies a series of protected wetlands and rivers and on the other side, a golf course winds along the road and then disappears around a corner. Just past these idyllic scenes is Cape Town’s oldest black township, Langa (isiXhosa for ‘Sun’), established a couple decades before apartheid. At one time, this was the edge of the city and Langa was established as a “temporary” labor camp where black, “migrant” workers could be kept safely away from white city and suburban spaces after work hours.

Forty years later, Langa feels like it is almost part of downtown Cape Town as urban development has pushed the boundaries of the city back twenty miles or more in all available directions. As urban economic growth and rural poverty fueled ever-increasing inflows of people looking for work, townships were constructed along the spine of the N2 to house this growing population. One by one, new townships appeared further and further along the path of the N2—Gugulethu (‘Our Pride’), Nyanga (‘Moon’), Crossroads, KTC, Philippi, and Brown’s Farm.

The economic expansion in Cape Town and its growing population, however, did not translate into increasing wealth for township residents and nearly twenty years of political freedom have also failed to provide economic progress for the majority of Cape Town’s residents. Wages and infrastructure continue to be relatively better than in the rural areas, but the disparity between the rich and the poor, or even between the middle class and the poor, continues to be dramatic in these urban areas (Gumede 2015).

The townships that lie on either side of the N2 have eventually become home to almost three million residents, most of them black, Indian, or Coloured. The growth of these townships continues today as people from economically depressed rural areas come to Cape Town to join family members and seek employment. The corrugated iron shacks that are the homes for many of these recent arrivals in the “informal settlements” (or “squatter camps”) can often be found just a few meters from the edge of the highway and are some of the first sights visitors take in on their trip from Cape Town’s international airport to the city center. In the winter, the smell of wood, coal, and paraffin smoke blows across the highway and in the summer, blocked sewage lines and grass and house fires remind those driving through of the lack of dependable basic services in most of these areas. The highway is also a frequent scene of pedestrian deaths among the many thousands of people who are forced to cross this highway on foot to visit neighbors or go shopping.

Past the airport, a stretch of protected swamps and grasslands—home to hundreds of endangered species of field flowers—briefly replaces the sight of the burgeoning squatter camps until Khayelitsha (‘New Home’) comes into view on the right side of the highway. Situated at the outer edge of the Cape Town metropolitan region, Khayelitsha is one of the largest black townships in South Africa, home to nearly a million people, most of whom are formally unemployed. Like the more famous Johannesburg township of Soweto, Khayelitsha includes several (though not all) class strata, ranging from the homeless and those living in metal shacks in informal settlements to what might be characterized as lower-middle-class housing in the older, more established parts of the township.

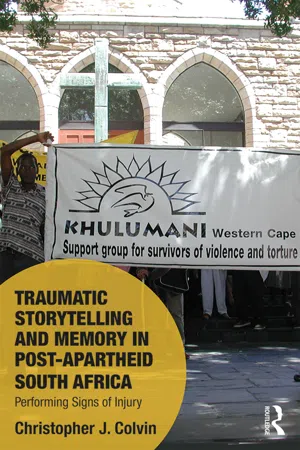

During my fieldwork, I lived in Observatory, conducted most of my formal research with Khulumani and the Trauma Centre near the city center, and often visited Khulumani members at their homes in the townships that spread out along the N2. This highway was the thin ribbon that joined together my several research sites, whether it was the NGO world of the city, the student/researcher haven of Observatory, or the townships that lined both sides of the highway on its course through the Flats. This thin slice of Cape Town is only one part of a very complex and changing urban landscape. It captures, though, something of the radically and persistently segregated social and physical spaces in South Africa that remain the most tangible and visible traces of apartheid (Afrikaans for ‘separateness’). Despite the many significant changes and improvements in the more than two decades since the first non-racial democratic elections in 1994, the sharpness of the contrasts produced by the post-apartheid city has faded little.

Seeking the “poorest of the poor”

It was another highway, though, the N1, that took us on the trip that I briefly recounted in the Introduction. This was a recruiting trip organized by Khulumani to meet with victims of apartheid-era political violence in some of the nearby rural towns outside of Cape Town. Colette Gerards, an anthropology graduate student visiting from Holland, and I set out early one Saturday morning for Khayelitsha to pick up the three Khulumani members who would be coordinating the recruiting. Though Khayelitsha is the largest township in Cape Town, most of the Khulumani members were women who came from the smaller townships near the airport like Philippi and Nyanga. Monwabisi Maqogi (or Monwa) and his two companions were some of the few Khulumani members from Khayelitsha and were also some of the only male leaders within the group. We met them at Monwa’s shack. Monwa had been trained in exile by Umkhonto we Sizwe (isiXhosa for ‘Spear of the Nation’ and abbreviated as MK), the armed wing of the African National Congress (ANC). He had been imprisoned and tortured upon his return to South Africa and was now active in Khulumani.

Introductions were made all around when we arrived and the kettle was put on for coffee. After these greetings, Monwa excitedly pulled out a brand new volume of academic essays entitled After the TRC (James and Vijver 2001). He asked if I had seen it yet. He had recently been to the book launch and was proud to own a copy of such an expensive item. He showed me the first chapter and described how each page contained the photo and story of a victim in Zwelethemba, one of the rural townships we were to visit on this trip. He said that we could expect to meet several of the people in this chapter on our journey.

After I had inspected it, Monwa put the book away and the two other members of the delegation, Mzwandile Jacob and Mncedi Mkhwebane, soon arrived. We started packing the car, loading bags, blankets, pillows, cigarettes, cassette tapes, and food, and we set off for Zwelethemba, Nkqubela, and Zolani, three black townships that are part of the (still mostly white) rural towns of Worcester, Robertson, and Ashton.

Worcester, the first town on our itinerary, was about an hour away. Like most small towns in South Africa, it is centered around a main commercial avenue peppered with the predictable chain stores selling discount clothing, groceries, fast food, petrol, and furniture. Anchoring many of these towns, geographically and spiritually, is the Nederlandse Gereformeerde Kerk (Afrikaans for ‘Dutch Reformed Church’), until recently the principal spiritual apologist for apartheid and still heart of the conservative Christian values that undergird Afrikaner culture throughout South Africa. We passed quickly through the town center of Worcester on our way to Zwelethemba. Located between the far edge of the town and the outlying commercial agricultural fields, Worcester’s townships, like Cape Town’s, are situated in a peri-urban space that makes transportation to town and to work difficult, time-consuming, and expensive, despite Worcester’s small size.

Like most black townships, Zwelethemba (isiXhosa for ‘Place of Hope’) has a core of longer-established, cement block and plaster homes at its center. Along the highway were tiny, brightly painted “RDP houses,” small, two-room dwellings in pastel pink, yellow, and blue. These were more recently built as part of the government’s Reconstruction and Development Program (RDP) to provide low-cost (but matchbox-sized) housing for the urban and rural poor.

We were there to recruit people who, because of their poverty and rural isolation, were not able to travel to Cape Town and access the kinds of resources offered by the Trauma Centre and Khulumani. In Monwa’s words, we were looking for the “poorest of the poor,” a constituency he assured us could be found in these rural areas. Both Khulumani and the Trauma Centre had recently become quite interested in doing rural outreach work outside of Cape Town. Khulumani wanted to recruit new members to grow its Cape Town operation. The Trauma Centre had begun assessing the needs and perspectives of these rural communities to determine if there was room for the Centre to extend its work. Since this was my first trip to these rural areas, I decided to ask few questions, keep a low profile, and explain that though Colette and I were conducting research at the Trauma Centre, we were on this trip mainly as volunteers for Khulumani.

The reasons for my reticence were several, including the fact that I had been warned by the Trauma Centre that these areas, and especially Zwelethemba, were “difficult” places. What I knew about Zwelethemba at this point was that it, like many townships, had been active in the anti-apartheid struggle. Despite my queries, however, no one really elaborated on the meaning of “difficult.” Most of the therapists, as well as many Khulumani members, simply warned me that working in Zwelethemba would not be an easy task.

Like many urban townships, Zwelethemba was built on a windy, sandy patch of ground with few shade trees. I was told several times before our trip that it was safe by Cape Town standards, meaning that my friends in Khulumani felt comfortable walking with Colette and me at night, something they never would have done in Khayelitsha. Our first port of call was Mzwandile’s uncle’s house in the older part of town for lunch and strategizing. His house boasted a fairly large yard and even a few shade trees in the back. A battered 16-seat minibus taxi sat in the driveway. We were led through the side door into a small sitting room with a sofa and two chairs, coffee table, and entertainment center, all dusted liberally with large lace doilies of various sizes, colors, and shapes.

The women of the household appeared, greeted us, and then retreated to the kitchen to prepare lunch. In the sitting room, the conversation careened from politics and witchcraft to the relative merits of Isidingo and Generations, two popular South African soap operas. Monwa passed his new book on the TRC around the room and there were delighted squeals of recognition as people saw the photos and read the stories of their neighbors down the road. Monwa also began speaking about the importance of spreading the “gospel of Khulumani.” In between frequent pauses to catch scenes of the soccer game on TV, he spoke about the lost generations of the “young lions” (youth who were mobilized against apartheid in the 1980s), divisions within and between communities, and the lure of drugs and crime for unemployed youth. He argued that Khulumani was in a position to address many of the problems of people in the townships who had been left out of the “new dispensation.”

Lunch was soon served, slices of white bread packed with margarine, cheese, and bologna, and after lunch, we set off to begin recruiting. Our first visit was to the house of a prominent local activist, Nowi Khomba. Monwa had spent time in Worcester in the later years of apartheid and Nowi was part of his network of contacts with local activists and ex-political prisoners. In due course, Gertrude Louw (Ma Louw) and Marshall Majola joined us around the heavy, dark table that filled Nowi’s dining room and our first meeting began.

Monwa began describing the goals of Khulumani, emphasizing that it was an organization for everyone who had been victimized by apartheid, not just those who had been imprisoned or had worked in the armed resistance. He explained both Khulumani’s position on the TRC (fighting for reparations for victims and against amnesties for perpetrators) as well as its plans for work beyond the TRC (economic empowerment programs, skills training, and oral history projects). At the end of his brief introduction, he pulled out some membership forms. Nowi objected, however, on the grounds of protocol, and said that first a larger group of interested community members would have to hear about Khulumani and if they approved, a general community meeting should next be held so that everyone could hear about and comment on the project. Only if this general meeting approved of the project could the business of membership forms be raised again. Everyone at the table agreed that this was the correct procedure.

Rallying the community

Our next stop was to the home of Yvonne Khutwane, the visit described in the Introduction. Despite her ambivalent interactions with me around storytelling, her support for Khulumani was clear and she seemed excited to become part of its work. Nowi felt that Yvonne’s endorsement of Khulumani was enough to proceed and we retired back to her house for another, slightly larger committee meeting. While we were waiting for everyone to assemble, Monwa presented his TRC book to Nowi, to whom a page was devoted in the first chapter. He was eager to see her and other’s reactions to the stories in the book. They were not pleased, however, to hear the news that the book had been published and a loud and angry conversation ensued as they passed the book around and shook their heads. They had apparently agreed with the researchers who wrote the chapter that they would have more input on the final product.

When everyone had arrived, however, the book was put away and the meeting began. It was, for once, mercifully short of debate over procedure—or the dilemmas of engaging with researchers—and a decision was soon taken to hold a general meeting in the local community hall the following evening for the whole community. They also decided to rent a pickup truck and loudspeaker that afternoon to advertise the meeting throughout Zwelethemba. After some haggling over the cost of the pickup rental, we piled in. For the next two hours, we drove around Zwelethemba’s potholed and windswept roads while Monwa and Mzwandile took turns proclaiming the injustice of the TRC, the betrayal of victims by those in power, and the need for Khulumani to represent those whom the transformation had passed by.

The TRC had recently recommended that the government pay reparations to the victims that had testified to the Commission and Khulumani’s fight to force the government to pay these reparations figured prominently in Monwa’s calls to join Khulumani. This was despite the fact that those of us in the truck all knew that relatively few people in this community, or in any community, had previously submitted statements to the TRC. Submitting such a statement was a prerequisite for any reparations payout and only about 22,...