![]()

1 Introduction

Countering climate change is held by a global consensus (as represented by the Paris Agreement) as being one of, if not the most, pressing challenge(s) of our age. From both a public policy and an academic point of view there is a great need to understand the drivers of policy outcomes. This book is a contribution to this need. The book focuses on the electricity sector. Of course there are various other important elements to the task of reducing greenhouse gas emissions (including increasing energy conservation), but I focus on electricity supply for two reasons. First it is a more manageable analytical task to accomplish than a broader approach. Second, electricity is expanding the range of services that it can meet, and is therefore becoming more important to issues facing climate change mitigation.

We are witnessing some outcomes that many would have thought fanciful 50 years, or perhaps even 20 years, ago. Renewable energy sources, especially wind power and solar photovoltaic (pv), are declining rapidly in cost and are being deployed at increasing rates across the world. Meanwhile nuclear power seems to be relatively expensive, and its rates of deployment have been slow compared to expectations of nuclear power expansion, and most recently expectations of a ‘nuclear renaissance’. I will discuss how such outcomes have occurred by analysing the ways that differing cultural biases contribute to these technological outcomes.

A summarised description of the book

Since the 1950s there has been a consensus in society that fossil fuels have to be replaced by non-fossil energy technologies. The arguments for such change have varied from the need to avoid fossil fuel depletion to, over the last 30 years, an increasing emphasis on countering climate change. In the 1950s hierarchical monopoly electricity utilities were the main institutions charged with delivering nuclear power. Nuclear power is a centralised means of generating energy, with nuclear power being organised in a ‘top-down’ fashion by governments and international organisations. Yet egalitarian forces in the shape of the greens challenged dominant centralised hierarchies in the energy field. They are now in the process of overcoming their original critics, ironically with assistance of liberalised market capitalism whose bias was long thought to be against them.

Initially, in the 1970s and 1980s, it was green campaigners (allied with some interested engineers) who were the major political force to champion renewable energy sources, especially wind power and solar power. But then, by appealing to the public to induce governments to incentivise renewable energy deployment, they prompted governmental hierarchies to allow their preferred technologies to gain market share. In the process, the technologies were optimised and achieved greater economies of scale. Meanwhile nuclear power was beset with attacks on its safety and environmental impacts from the greens. Despite the added imperative of the need to combat climate change arising since the end of the 1980s, the deployment of nuclear technology has stalled, especially in Western countries. Its deployment has been hampered because of the increasing construction costs associated with the need to meet safety requirements. The relatively modest supply of new nuclear plants which are being built can be explained by hierarchical cultural bias and associated electricity monopolies who can absorb the extra costs.

On the other hand, as the costs of renewable energy have fallen, renewables have begun to prosper through liberalised markets, markets where hierarchies cannot impose their more expensive nuclear solutions. This decentralised approach sees renewables allied with battery storage and demand side response techniques. Liberalised energy markets, allied with the increase in power of digitalised, information technology systems, allow such decentralised energies and technologies to gain traction. In doing so an effective alliance between green cultural biases and individualistic, market oriented biases gathers force. It propels a decentralised energy revolution forward, one which is eroding the old centralised technological regimes and side-lining nuclear power technologies.

A brief introduction to cultural theory

I am going to perform the analysis using ‘cultural theory’. I advance a claim in this book that it is not so much a matter of technologies being constructed to deal with climate change. Rather, I argue that climate change is used as a means of advancing technologies that are preferred by differing cultural biases. These biases drive pressures for different technologies and constraints on these technologies. Moreover, cultural biases inform policymaking processes and also the electricity industry institutions themselves, hence in turn influencing technological outcomes.

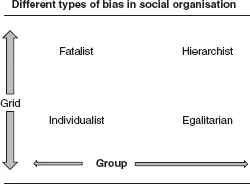

I can make a brief summary of these cultural biases on the basis of cultural theory (Douglas 1982; Douglas and Wildavsky 1982; Olli 2012; Rayner 1992; Swedlow 2011; Tansey and Rayner 2008; Toke and Baker 2016). They are fourfold, in relation to energy and environment: hierarchy, which implies centralised decision making in favour of state security objectives – decision making which biases outcomes towards solutions favoured by established interests, and especially, in this context, nuclear power; egalitarianism as represented by green political pressures, which favours decentralised energy solutions to meet environmental objectives and keep impact on the environment within the ‘carrying capacity’ of the planet and which biases outcomes towards renewable energy; individualism, which prioritises solutions that meet consumer requirements on the basis of lowest cost within market competition; and fatalism, which involves acceptance of the rules and little belief in making changes to improve outcomes – perhaps the least studied as an influence but the most common bias among consumers.

As can be seen in Figure 1.1, the biases spring from a ‘grid v. group’ comparison, wherein on the vertical axis the degree of social organisation (involving rules) increases upwards, whereas on the horizontal axis the degree of group affiliation increases to the right.

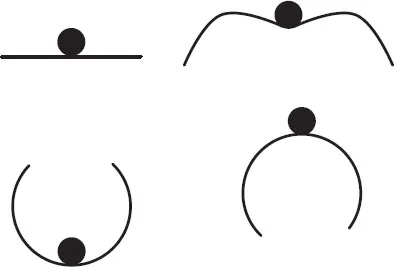

This schema is translated into attitudes on the environment for each of the four named biases, as pictured in Figure 1.2 below.

As is pictured in Figure 1.2 Hierarchist (top right) will see the environment as being capable of being managed within certain limits; egalitarians (bottom right) will see ecology as being fragile and precarious, individualists (bottom left) will see the environment as being robust and resilient, and fatalists (top left) will see the environment as being unpredictable and as something that cannot be controlled.

I argue that egalitarian, green, cultural pressures have dominated in producing energy supply outcomes in low carbon sources of energy. This bias has involved grass roots movements deploying, even developing, technologies themselves and, of especial importance, pressuring governments to give incentives for decentralised renewable energy sources. These have created markets for renewable energy that have created economies of scale which have further reduced costs, in turn making viable electricity systems more tailored to variable renewable energy sources. In this process individualist biases have, despite their initial hostility to ‘expensive’ renewable energy sources, become allied to the deployment of renewable energy since they have become lower cost and more suited to market based competition.

Figure 1.1 Different types of cultural bias in social organisation.

Source: adapted from Figure prepared by Keith Baker, reproduced from Toke and Baker (2016, 447).

Figure 1.2 Cultural bias and nature.

Source: prepared by Yvonne Toke, adapted from Steg and Sievers (2000, 54, Figure 1).

Hierarchical bias has tended to favour nuclear power. Yet despite this advantage nuclear power has failed to grow as a proportion of electricity supplied around the world as a whole in the context of frequent egalitarian opposition. This opposition has had the effect of increasing demands for safety measures which have pushed up the cost of nuclear power. Hierarchies, whose task is managing for system stability, have been obliged to allow this increase in safety criteria as a price to accommodate the opposition to nuclear power. Individualist bias has been sceptical of the environmentalist concerns about nuclear power. Yet, as nuclear power has appeared to be expensive, individualist bias becomes less sympathetic towards nuclear power. Some of the same outcomes can be seen with carbon capture and storage (CCS), another solution put forward by hierarchies from the existing energy establishment. This technology has evinced little enthusiasm from egalitarians, and little interest among individualists on grounds of cost.

We cannot create a counterfactual world to see exactly what would happen to energy if climate change did not exist as an issue. However, we can analyse the energy politics of egalitarianism, as discussed in Chapter 5, and see that in broad terms egalitarian positions were much the same then as now.

Arguments about energy and environment were covered in Douglas and Wildavsky’s seminal text on risk (Douglas and Wildavsky 1982), and this work is especially significant for this book since they used cultural theory to analyse how risk was socially constructed. Their arguments were generally conservative ones, implying that green egalitarian campaigns such as that against nuclear power could imperil the hierarchy’s efforts to achieve economic development. They argued that severe impacts on the economy could be the price to pay for absorbing socially constructed notions of risk.

Cultural theory and ecological modernisation (EM)

In this book I revisit some of these debates opened up by Douglas and Wildavsky (1982) but suggest a way in which cultural theory can be used to understand some different outcomes from those implied by their analysis. Ecological modernisation (EM) implies a different outcome in that EM involves a positive sum outcome for the environment and economy.

So how is it that cultural influence contributes to such a possibility that egalitarianism may be involved in a process that leads to economic development rather than the more negative nuances implied originally by Douglas and Wildavsky? A key theoretical aim of this study is to bridge this gap, to examine how cultural theory can be invested, melded, with EM theory. Potentially this can help develop EM since a theory that is associated with technological implementation can be linked with, and its progress more understood by, cultural forces that drive social processes.

I need to briefly explain the basic character of EM, in which case I shall quote a description I set down in an earlier book I wrote on renewable energy:

essentially, the idea of EM is that it combines economic development and environmental protection as a way of conducting good business; ‘in short, business can profit by protecting the environment’ (Carter 2007, 226). EM’s central theme is that consumers demand higher quality, environmentally sustainable, goods and services and business responds to this pressure, so increasing economic development. This produces a ‘positive sum’ solution whereby economic development is increased, rather than decreased by environmental protection and where policy ‘conceptualises environmental pollution as a matter of inefficiency, while operating within the boundaries of cost-effectiveness and administrative efficiency’ (Hajer 1995, 33). EM demands a holistic response by industry to environmental problems; that is, policies must be considered for their total environmental impact, rather than environmental policy being limited to one-off ‘end of pipe’ responses (Weale 1992). EM can be said to be a theory that u...