eBook - ePub

Design and Visual Culture from the Bauhaus to Contemporary Art

Optical Deconstructions

- 194 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book complements the more textually-based Bauhaus scholarship with a practice-oriented and creative interpretive method, which makes it possible to consider Bauhaus-related works in an unconventional light. Edit Toth argues that focusing on the functionalist approach of the Bauhaus has hindered scholars from properly understanding its design work. With a global scope and under-studied topics, the book advances current scholarly discussions concerning the relationship between image technologies and the body by calling attention to the materiality of image production and strategies of re-channeling image culture into material processes and physical body space, the space of dimensionality and everyday activity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Design and Visual Culture from the Bauhaus to Contemporary Art by Edit Tóth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1Introduction

Arguably, the Bauhaus was the first internationally acknowledged institution that formulated a coherent attitude towards modern design and its relation to the emerging image culture. Do its concerns still have relevance for us in our twentieth-first-century world of seemingly endless supply of consumer products and image flow? The answer is “not really” if we content ourselves with the rigid view of Bauhaus design promulgated by postmodernism (to some extent based on the school’s own rhetoric), which exhausts itself in an obstinate pursuit of rationalism and functionalism, and a naive social utopia. Based on this understanding of the institution, contemporary design studies similarly view the Bauhaus as monolithic and outdated. Recent exhibitions, from the 2008 MoMA Bauhaus show to the Moholy-Nagy exhibitions at the Bauhaus Museum in Berlin (2014) and the Guggenheim Museum in New York (2016), and publications have nevertheless shown growing interest in the Bauhaus and its artists, yet they have failed to explain what substantiates this interest today beyond the current revival of the art-science-technology paradigm in cultural discourse.1 Can we critically understand Bauhaus design’s complex relation to visual culture and ask what its ongoing critical legacies may be? To recognize its import, it would be profitable to think of design in a broad sense, and as a practice rather than a product, as a practice still embracing multiple meanings, as it was thought of right before its final separation from artistic and handcraft practices.

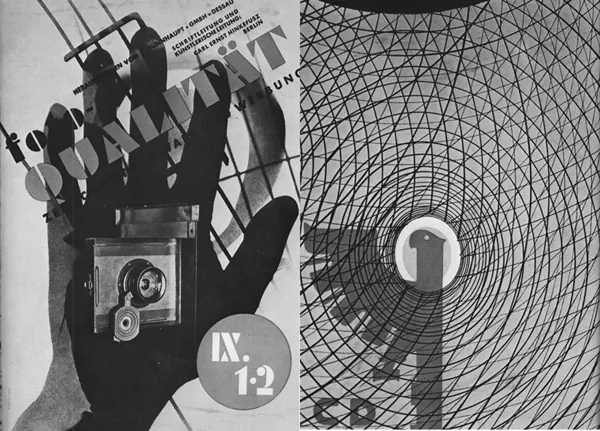

Although photography became part of the Bauhaus curriculum only in 1929, after László Moholy-Nagy left the school, students enthusiastically experimented with its various techniques inspired by his and other leading artists’ photograms, photomontages, New Vison pictures, and “typo-photos” (combination of photography and typography) from about 1925. While not made for a Bauhaus publication, Moholy-Nagy’s cover for the 1931 first issue of the magazine Foto-Qualität (Figure 1.1) carried out after he left the Bauhaus helps illuminate an important aspect not merely of Bauhaus advertising or graphic design but of Bauhaus design in general. Instead of matching the photographic camera with the eye, as in Dziga Vertov’s famous “camera eye,” for instance, the artist juxtaposed it with the hand, highlighting its function as a hand tool. The picture insists that the camera is more than a “mechanical eye;” it helps to transform and question the world around us. Nevertheless, the camera that carries out the transformation in the picture is not one of the latest models. Rather, it appears to be an early camera, which operates with a visibly and manually assembled glass plate, mirror, lens, and framing aperture. The process of creating an image with it requires technical skill and hand manipulation, not unlike playing on the strings of a guitar or constructing an object. As the back cover suggests, with proper maneuvering and experimentation, its mechanism may open up new vistas, vortex-like spaces of possibilities, and latent meanings inherent in our surroundings, overcoming its inbuilt one-point perspective view and challenging our automatic acceptance of its conventional rationalized framework.

Figure 1.1László Moholy-Nagy, Front and back cover for Foto-Qualität, 9, nos. 1–2. 1931. Courtesy of Hattula Moholy-Nagy.

The subtitle of the book, “Optical Deconstructions,” is a somewhat unusual juxtaposition of terms, which in the critical discourse of postmodernism were frequently regarded as oppositional. Derrida, and post-structuralist theories inspired by him, offer deconstruction as a textual event intersecting discourse, an effort meant to counter the prevailing dominance of visual culture.2 The type of visual culture and opticality I am interested in is that which is grounded in material culture and practices such as camera optics and technical processes. Modernist opticality, including the “optical unconscious” evoked by Walter Benjamin and reworked in Rosalind Krauss’s Optical Unconscious in Freudian terms, can certainly be extended in different directions and its critical potentials re-evaluated, avoiding the dualism she employs to oppose the pure vision of Greenbergian “high modernism.”3 Modernism developed a variety of means to access cultural and social issues related to the image culture of its time, even if they were not as radical as postmodern methods. Bauhaus-type optical deconstructions involved more than an empiricist practice of elementarizing things. Embracing difference, they constituted the reverse side of the coin occupied by the school’s official program of universalizing functionalist rationality. Since the deconstruction derives from experimentation with materials and the taking apart of photographic processes, visual culture becomes “deconstructed” in the artwork, allowing for different “Derridian” readings. Given the works’ interactive or process-like character, their changing—visual, spatial, and historical—context generates different meanings. Although allied with a social agenda, Bauhaus-type opticality is also compatible with contemporary interpretations of opticality, especially as related to immersive video installations, where it is understood as haptic, visceral, and bodily inscribed. Therefore, modernist deconstruction is less a negation than a—sometimes utopian, sometimes pertinent—proposition, an imagining visual culture otherwise.

The present study examines the ways in which photography and filmmaking as new models of artistic practice and vehicles for optical deconstructions expanded design possibilities. I want to emphasize that the book does not contain a survey of the design institution called the Bauhaus, nor does it lay out a universally accepted and methodically pursued design method. Rather, the reader is offered a collection of case studies directly or indirectly converging around the Bauhaus that include diverse geographic locations, such as Germany, the United States and Japan, and varying contexts, from the 1920s to the late modernist era of the 1950s, and ultimately to contemporary art. The case studies excavate various historical strategies of design that involve photographic images made by the artists, as well as photographic transcoding, that is, inspiration taken from photography understood as a material process and optical technology that can alter or reframe our view of the world. Did the design in those cases offer access to the transformation of the self, physical and social space, and critical thought, or only to concerns of utility or the exchange of subjectivities as perpetuated by media and consumer products? Furthermore, can we trace comparable reframing of the world, directly or indirectly related to the Bauhaus model, in contemporary art and design, relevant for current issues, which go beyond mere perceptual games and immersive affects? These are the questions the book explores through case studies of experimental projects that strove to reformulate the relationship of art, design, technology, media, and the social self. They address problems of embodiment and spatiality, technologies of the self and of vision, nihilism, and the dangers of Western metaphysics, as well as the perceived disappearance of the public sphere and with it modernism’s hope for bringing about social change.

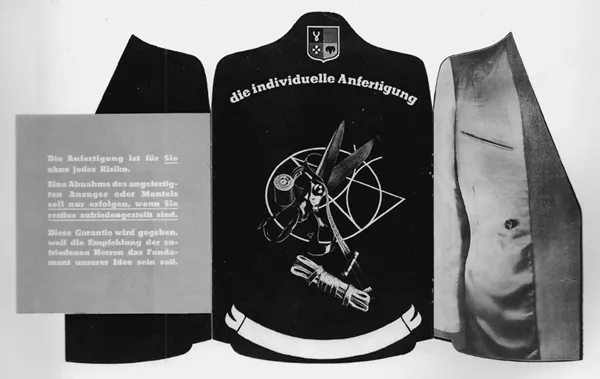

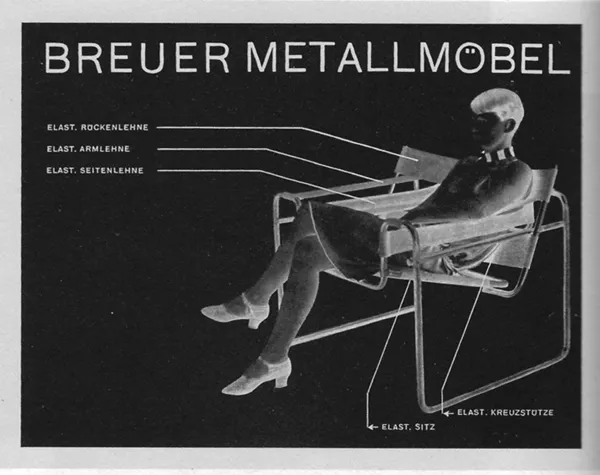

The Bauhaus was among the first to recognize photography’s central importance in commodity culture and the fact that, more than style—in this case machine aesthetic—photography provided access to the social sphere and the means through which to contest social conventions or negotiate social integration. While participating in the dissemination of image culture, Bauhaus artists nonetheless recognized that the evolving proliferation of images and signs severed from their referents precipitated the development of abstract relations between people and things and devised characteristically modernist ways to address it. Even though the focus of the book is not the deployment of photography in advertising design, we should keep in mind that the majority of Bauhaus advertisements complemented the type of Bauhaus design I am addressing here.4 Take for instance Moholy-Nagy’s unfolding suit-shaped brochure Die individuelle Anfertigung (1932, Figure 1.2), designed after he left the Bauhaus, which shows the tools used to make it (as a sign of honest work) when opened up, emphasizing the image’s objectness and materiality more than its status as an image. Herbert Bayer’s title page for the Breuer Metal Furniturebrochure (1927, Figure 1.3) presents a woman sitting in a tubular chair, again referring to the materiality of the photographic image in the form of a photographic negative that simultaneously serves as a “diagram” explaining the various parts of the chair. In turn, Grete Stern and Ellen Auerbach’s (working under the name ringl + pit) hair dye advertisement for Komol (1932) highlights the image’s constructed artifice by placing artificial hair samples over a wire mesh. In these cases, appeal to desire and fantasy is de-emphasized by the highlighting of materials, processes of making, and unfamiliar ways of encounter. Although this outdated “materialist” type of advertisement that transformed Russian Constructivist practices for a German context, and which is enlightening more than seductive, would clearly not sell today, it illuminates the concerns of its designers.5 Bauhaus advertisement, in fact, was an offshoot of exhibition design, in which objects, images, and words intermingled, and where images did not lose their referents, and images and words challenged each other. Exhibitions already belong in the world of commodity exchange, yet they are places where production, display, and image still remain under one “roof” and therefore, it was believed, they could be kept interrelated and played against each other. Rather than focusing on advertising photography, although keeping this practice in mind, the present study attempts to discover more mediated applications of and deconstructions through photography and film, in design, and their intermeshing with material processes that activate or point to the gap between production and consumer images. The book considers examples in which photographic principles, properties, techniques, and modes of operation found their way into the design of three-dimensional objects, which thus became “mediatized,” and it considers the various cultural issues and problems of subjectivity this mediatization was bound up with and brought to the surface. Although Bauhaus artists tried to shift emphasis from consumer subjectivities to the subjectivity of perception itself, since they designed everyday objects and living spaces, the two concerns became intertwined or produced tensions, a development which will be explored here.

Figure 1.2László Moholy-Nagy, Die individuelle Anfertigung, brochure, 1932. Courtesy of Hattula Moholy-Nagy.

Figure 1.3Herbert Bayer, Breuer Metallmöbel, brochure title page, 1927. © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

In place of the type of Bauhaus scholarship that is predominantly texturally oriented and often narrowly focused on individual artists or workshops, the book intends to offer practice-oriented interpretive methods that make possible an unconventional understanding of Bauhaus-related works, while participating in a shared appreciation of the power of objects. Scholars’ focus on the self-declared functionalist approach of the Bauhaus, which subsequently became a convention, has hindered the recognition of other cultural and social interests in the design work. The book proposes that Bauhaus artists’ optical deconstructions led to a variety of practical applications of phenomenology seeking to understand technology’s relation to the body and the self in a larger context. While immersing themselves in the problems of their age, in the aesthetics of technology, and practices of rationalization and visualization, artists associated with the Bauhaus retained an experimental attitude that sometimes differed, sometimes converged. The type of experimentation under examination here has to do with the transference of the technical model of photography over design work, which enabled seeing things in a different light and engaging the contingencies of modern life.6 One might argue that the development of phenomenology parallels that of photography and the invention of lighter, portable cameras that allowed for various ways of focusing and framing the world while being immersed in it. Phenomenology encouraged a shift in the understanding of the self and its relation to its surroundings. Modernist photography, in turn, discovered aspects of the urban environment and its social relations that everyday experience overlooked to generate renewed meanings for them, or to throw light on them from an unusual perspective. What the book thematizes is a practical application of phenomenology developed at the Bauhaus, which is rather distinct from contemporary theoretical philosophy as put forward by either Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, or Maurice Merleau-Ponty, although some common concerns emerge. In the designs and photographs, one may find common points with either Husserl’s idea of intentionally formed consciousness that is combined with object-based motivation, Merleau-Ponty’s notion of bodily perception, Heidegger’s idea of place-forming as “being-there,” which emerges as part of our involvement with things in various situations, or the Kyoto School’s focus on bodily perception based in nothingness as a form of emptying. The point, however, is not to suggest or to try to prove that the writings of these philosophers, or those of other theoreticians who made use of phenomenological methods of investigation, directly influenced Bauhaus designers, but rather to generate constellations that problematize design work. The problematizing approach makes possible the consideration of Bauhaus-related works in a new light, as “mediatized” or “conspicuous” rather than fetishistic objects and spaces that call attention to the context of their experience, to the materiality of image production, and aspects of self-formation related to them. Interconnecting private and public realms, the designs alter our awareness of the potentials of appearances and set in motion unstable meanings, making conflicted claims about their applicability to integrative or critical social agendas. The last chapter traces comparable optical deconstructions in contemporary art and design, as well as their uneasy relationship to and reformulations of the modernist model.

In considering the social implications of early design and the issue of how design form shapes subjectivity, to some extent, Fredric Schwartz’s book The Werkbund: Design Theory and Mass Culture before the First World War, which explores Jean Baudrillard’s notion of the political economy of the sign in the field of design, charts the preconditions of my discussions.7 Schwartz explains how form, through the notions of style, Typisieriung (“type objects”), and the trademark, had been theorized and deployed by members of the German Werkbund—association of designers, architects and representatives of industry united in thei...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Information

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Orienting the New WomanBreuer’s Furniture and Complex Gender Expressivity at the Haus am Horn

- 3 Optical Improvisations: Jazz, Film and Moholy-Nagy’s Light Prop for an Electric Stage

- 4 Domestic Interventions: Marianne Brandt’s “Mediatized” Objects and Self-Portrait Photographs

- 5 “Taking Apart” the Sukiya: The Yamawakis’ Postwar Tokyo Homes

- 6 Vertigo and Kepes’s Light Art in 1950s America

- 7 Contemporary Art, Architecture and Media: Recovering Material Space

- Index