![]()

1 Political violence in context

The Portuguese armed struggle

The exercise of context reconstruction and exploration is very important for the understanding of how and why politically violent organisations came into existence in Portugal in different periods of time and in different socio-political conditions. This volume focuses solely on political violence committed by non-state actors. However, in this chapter and throughout Chapters 3, 4, and 5, the accounts provided by relevant literature and my interviewees will also touch on the issue of state violence, particularly in the Estado Novo period (1926–1974). This era is also known as Salazarismo, after its instigator and then ruler (1932–1968), António de Oliveira Salazar. Salazarismo represented the embodiment of power and a strong state organised around a strong individual, which it was thought could eradicate the perceived chaos of the First Republic. Salazar was the answer to the demands for an authoritarian solution from certain sectors of Portuguese society who were strongly inspired by other European examples, particularly Italy’s Mussolini and Spain’s Primo de Rivera. Among those sectors were reactionary factions of the bourgeoisie, a significant proportion of the Catholic Church, and some intellectuals of the First Republic. In this context, Salazar started his journey to leadership by achieving financial balance to the country as minister of finance. In 1932, he agreed to lead the government. Finally, in 1933, he presented a new constitution that gave birth to the Estado Novo (a designation that Salazar himself coined for the regime he intended to rule). At that time, many Portuguese viewed Salazar as the “saviour of the homeland” (Amaro, 1982, p. 1007), which was submerged in financial, political, social, and cultural turmoil – issues that he pledged to resolve.

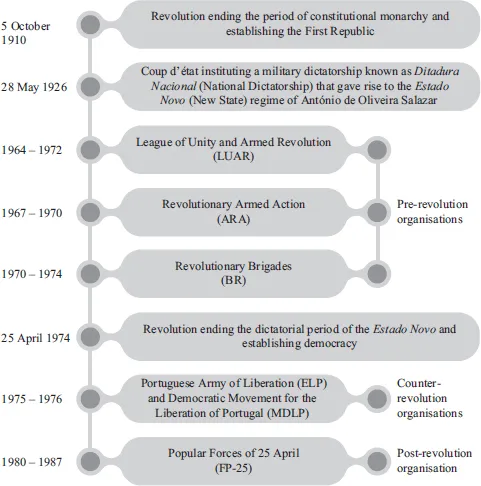

In this chapter, I shall identify the historical and political contexts in which six politically violent organisations emerged in Portugal over the course of a quarter of a century (1962–1987). During the first wave (1962–1974), in a very clear and direct way, the Estado Novo regime led to the emergence of the LUAR (Liga de Unidade e Acção Revolucionária / League of Unity and Revolutionary Action), the ARA (Acção Revolucionária Armada / Revolutionary Armed Action), and the BR (Brigadas Revolucionárias / Revolutionary Brigades). These three organisations fought against the regime and its policies, predominantly those relating to its authoritarian, imperial, and colonial stances. They resorted to violence against a regime that in their eyes was extremely violent and repressive and could not be defeated by peaceful means. The latter had been tried for years without success and at a high personal cost for numerous individuals who suffered arrest, torture, and forced labour.

In the second wave (1975–1976), the rise of the ELP (Exército de Libertação de Portugal / Portuguese Liberation Army) and the MDLP (Movimento Democrático para a Libertação de Portugal / Democratic Movement for the Liberation of Portugal) was triggered by fears of a possible communist takeover following the April Revolution and by antipathy towards some of the decisions taken by the provisional government (e.g., the decolonisation process). These organisations essentially comprised right-wing military personnel, who usually leaned towards the deposed regime.

In the third wave (1980–1987), the creation of the FP-25 (Forças Populares 25 de Abril / Popular Forces of 25 April) was motivated by a belief that the principles espoused by the April Revolution were starting to fade away, which was facilitating the re-emergence of the unjust society of the Salazar years. For some individuals, this situation could be resolved by nothing less than a socialist revolution.

Figure 1.1 provides a timeline of both the main historical events that set the context for the rise of armed organisations in Portugal and the periods when these organisations were active.

In the beginning was Salazar

The Estado Novo is a period of Portuguese history that has its origins in the military coup of 28 May 1926. This coup ended the First Republic, which had only begun on 5 October 1910 after ninety years of constitutional monarchy (1820–1910). The First Republic was always plagued by great difficulties of consolidation, as Fernando Rosas (1989a) explains. For instance, in the course of its sixteen years, there were forty-five governments and ten coup attempts. Moreover, in 1918, one of the First Republic’s eight presidents, Sidónio Pais, was assassinated. Thus, while the military dictatorship established after the coup of 28 May 1926 did not have a well-defined ideology, it was deeply sceptical about the effectiveness of parliamentary democracy and it aimed to restore the Catholic Church’s paramount role in the socio-political life of the country (Baiôa, 1994).

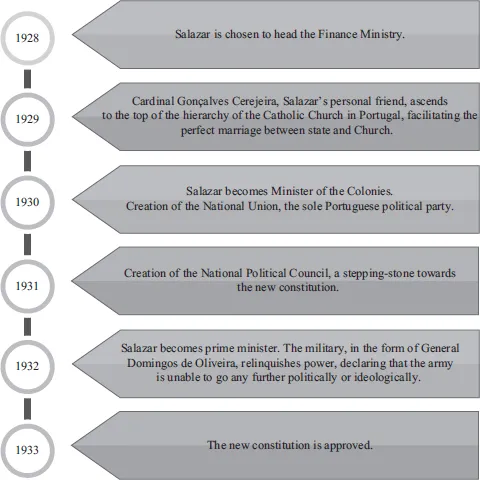

In the first months of the military dictatorship, the fight for power between liberal–republican and conservative factions was won by the latter. However, there were two different groups of conservatives: one that advocated conservative republicanism and another that supported Salazar (Pinto and Rezola, 2007). The first group considered the military dictatorship as a necessary but transitory regime whose role would end once order was restored and a constitutional regime secured. However, it had a poorly defined strategy of government, weak internal cohesion and weak leadership, all of which contributed to its ultimate failure. A financial and economic crisis ensued, which meant that all attention and hope for the future turned to Salazar. This figure from the Catholic centre had extensively criticised the financial policies implemented by the conservatives who headed the first government, having resigned from his role as economist in the cabinet due to the continuing social and political instability. Nevertheless, in 1928, Salazar accepted an invitation to head the Ministry of Finance, which made him a very powerful minister in the difficult financial situation that Portugal was experiencing (Wheeler and Opello, 2010). In addition to his financial solution for the country, which envisaged a balanced economy and kept him in the same position through several changes of government, he developed a political programme – the foundation of a new political, economic and social order based on an authoritarian state (Oliveira, 1990). Thus, Salazar’s political plans developed in his first years in office, culminating in the promulgation of a new constitution, as represented in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Salazar’s consolidation in office

In order to accomplish his mission, Salazar based his regime on a mythical idea of nationhood. Also, similarly to Europe’s fascist regimes, he aimed to create a new type of Portuguese citizen, regenerated by the regime’s ideology. Such an ideological totalising project had its apogee in the 1930s and 1940s and defined an aggressive propaganda discourse that aimed to re-educate the Portuguese people in the context of a regenerated nation (Rosas, 2001). These stances embodied by the Estado Novo were summarised by Salazar himself in a speech he delivered in 1936 to mark the tenth anniversary of the military coup. This speech clearly infantilised the Portuguese people and neutralised their freedom of thought, speech, organisation, and emancipation:

To the souls torn by doubt and negativity of the present century, we look to restore the comfort of the great certainties. We do not discuss God and Virtue. We do not discuss the Nation and its History. We do not discuss Authority and its Prestige. We do not discuss Family and its Morals. We do not discuss the glory of work and duty.

(Salazar, 1946, p. 130)

In order to exercise its authority as widely as possible, the Estado Novo fashioned and implemented a number of societal structures. Among those, three were central to triggering the activities of armed organisations in Portugal. First, there was the absence of political freedom. The multi-party system was deemed disruptive to the unity of the nation because different parties were viewed as representing individual ideas and interests. Therefore, only one party was allowed: the União Nacional (National Union). Moreover, the 1933 constitution granted vast powers to the president of the Council, including the ability to legislate by decree, to appoint and remove members of the government, and to ratify any acts introduced by the president of the Republic (Pinto, 1999). It also mirrored the Estado Novo’s corporatism, which brought the socio-professional life of each individual under the auspices of the government (Lucena, 1979).

Second, there was the absence of freedom of expression. In order to control and restrict public opinion and any debate about or criticism of the regime, the Estado Novo implemented mass media censorship both in Portugal and abroad (Cabrera, 2014). From books to magazines, radio broadcasts to cinema, theatre shows to song lyrics, anything that could be seen as endangering the regime’s interests had to go through the Censorship Bureau. This bureau created specific “criteria” to justify its “prohibition and seizure” (Fonseca, 2005, p. 22) of unacceptable material. For example, there was a long list of forbidden themes, including: political contestation, political prisoners, colonies and civil war, agrarian reform, religion, socialist ideology, poverty, peasants’ and workers’ living conditions, social inequality, morals, customs, and sexuality. A “rule of silence” was imposed through censorship that affected not only the mass media but also everyday life. This gave rise to “self-censorship” and “inner repression”, both of which fed people’s “fear of imprisonment, fear of aggression, fear of losing a job, fear of causing harm to the family, fear of being frequently bothered by anonymous phone calls, [and] finally, fear of persecution” (Gama, 2008, p. 225).

Third, there was the political police. According to Irene Pimentel (2011), this force was organised around three main functions: to dissuade the general population from conspiring against the regime; to punish individuals who tried to conspire against the regime; and to arrest individuals who were involved with subversive parties and organisations, particularly the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP). The pattern of action followed by the political police involved detention, isolation of the detainee from any contact with family members or lawyers, and physical and psychological torture. The aim was to obtain confessions of oppositional activities and to spread fear across society through the destruction of the lives of particular individuals, who would then serve as examples for others (see more in Albuquerque, 1987; Pimentel, 2007; Cardina, 2010). When asked about this institutionalised violence and the mistreatment of prisoners in 1932, Salazar suggested that such actions were justified by the nature of the prisoners (“terrible bombers”) and by the need to protect vulnerable citizens (“children and helpless people”):

I wish to inform you that it has been concluded that the mistreated detainees were always, or almost always, terrible bombers who refused to confess, despite all the skills of the police, where they had hidden their criminal and deadly weapons. Only after employing such violent means are they able to tell the truth. And I ask myself, continuing to repress such abuses, if the lives of some children and helpless people are not well worth it and do not widely justify half a dozen shoves, at the right time, to these sinister creatures.

(Salazar quoted in Ferro, 1982, p. 54)

The political police also made full use of the Colónia Penal do Tarrafal (Tarrafal Penal Colony) in Cape Verde, commonly known as Tarrafal. Created in 1936 and falling under the authority of the political police, this was intended for “political and social detainees...